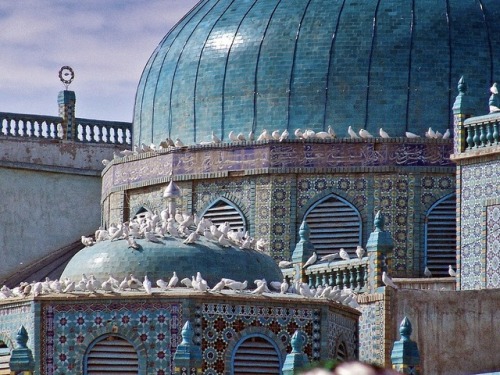

Unknown Photographer - Blue Mosque In Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan Photography

Unknown Photographer - Blue Mosque in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan Photography

More Posts from S-afshar and Others

History of Achaemenid Iran 1A, Course I - Achaemenid beginnings 1A

Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Tuesday, 27 December 2022

Outline

Introduction; Iranian Achaemenid historiography; Problems of historiography continuity; Iranian posterior historiography; foreign historiography; Western Orientalist historiography; early sources of Iranian History; Prehistory in the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia

1- Introduction

Welcome to the 40-hour seminar on Achaemenid Iran!

It is my intention to deliver a rather unconventional academic presentation of the topic, mostly implementing a correct and impartial conceptual approach to the earliest stage of Iranian History. Every subject, in and by itself, offers to every researcher the correct means of the pertinent approach to it; due to this fact, the personal background, viewpoints and thoughts or eventually the misperceptions and the preconceived ideas of an explorer should not be allowed to affect his judgment.

If before 200 years, the early Iranologists had the possible excuse of studying a topic on the basis of external and posterior historical sources, this was simply due to the fact that the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing had not yet been deciphered. Still, even those explorers failed to avoid a very serious mistake, namely that of taking the external and posterior historical sources at face value. We cannot afford to blindly accept a secondary historical source without first examining intentions, motives, scopes and aims of it.

As the seminar covers only the History of the Achaemenid dynasty, I don't intend to add an introductory course about the History of the Iranian Studies and the re-discovery of Iran by Western explorers of the colonial powers. However, I will provide a brief outline of the topic; this is essential because mainstream Orientalists have reached their limits and cannot provide us with a real insight, eliminating the numerous and enduring myths, fallacies, and deliberately naïve approaches to Achaemenid Iran.

In fact, most of the specialists of Ancient Iran never went beyond the limitations set by the delusional Ancient 'Greek' (in reality: Ionian and Attic) literature about the Medes and the Persians (i.e. the Iranians), because they never offered themselves the task to explain the reasons for the aberration that the Ancient Ionian and Attic authors created in their minds and wrote in their texts about Iran. This was utterly puerile and ludicrous.

And this brings us to the other major innovation that I intend to offer during this seminar, namely the proper, comprehensive contextualization of the research topic, i.e. the History of Achaemenid Iran. To give some examples in this regard, I would mention

a - the tremendous, multilayered and multifaceted impact of the Mesopotamian World, Civilization and Heritage on the formation of the Achaemenid Empire of Iran, and more specifically, the determinant role played by the Sargonid Empire of Assyria on the emergence of the first Empire on the Iranian plateau;

b - the ferocious opposition of the Mithraic Magi to the Zoroastrian Achaemenid court;

c - the involvement of the Anatolian Magi in the misperception of Iran by the Ancient Greeks; and

d- the utilization of the Ancient Greek cities by the Anti-Iranian side of the Egyptian priesthoods, princes and administrators.

To therefore introduce the proper contextualization, I will expand on the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Sargonid times, not only to state the first mentions of the Medes and the Persians in History, but also to show the importance attributed by the Neo-Assyrian Emperors to the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau, as well as the numerous peoples, settled or nomadic, who inhabited that region.

There is an enormous lacuna in the Orientalist disciplines; there are no interdisciplinary studies in Assyriology and Iranology. This plays a key role in the misperception of the ancient oriental civilizations and in the mistaken evaluation (or rather under-estimation) of the momentous impact that they had on the formation of the World History. There are no isolated cultures and independent civilizations as dogmatic and ignorant Western archaeologists pretend.

Only if one studies and evaluates correctly the colossal impact of the Ancient Mesopotamian world on Iran, can one truly understand the Achaemenid Empire in its real dimensions.

2- Iranian Achaemenid historiography

A. Achaemenid imperial inscriptions produced on solemn occasions

Usually multilingual texts written by the imperial scribes of the emperors Cyrus the Great, Darius I the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, Darius II, Artaxerxes II, and Artaxerxes III, as well as of the ancestral rulers Ariaramnes and Arsames.

Languages and writing systems:

- Old Achaemenid Iranian (cuneiform-alphabetic; the official imperial language)

- Babylonian (cuneiform-syllabic; to offer a testimony of historical continuity and legitimacy, following the Conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, who presented himself as king of Babylon)

- Elamite (cuneiform-logo-syllabic; to portray the Persians in particular as the heirs of the ancient land of Anshan and Sushan that the Assyrians and the Babylonians named 'Elam' and the indigenous population called 'Haltamti' / The first Achaemenid to present himself as 'king of Anshan' is Cyrus the Great and the reference is found in his Cylinder unearthed in Babylon.)

and

- Egyptian Hieroglyphic (if the inscription or the monument was produced in Egypt, since the Achaemenids were also pharaohs of Egypt, starting with Kabujiya/Cambyses)

Imperial inscriptions are found in: Babylon (Cyrus Cylinder), Pasargad, Behistun, Hamadan, Ganj-e Nameh, Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rustam, Susa, Suez (Egypt), Gherla (Romania), Van (Turkey), and on various items

B. Persepolis Administrative Archives

This consists in an enormous documentation that has not yet been fully studied; it is not written in Old Achaemenid as one could expect but mainly in Elamite cuneiform. It consists of two groups, namely

- the Persepolis Fortification Archive, and

- the Persepolis Treasury Archive.

The Persepolis Fortification Archive was unearthed in the fortification area, i.e. the northeastern confines of the enormous platform of the Achaemenid capital Parsa (Persepolis), in the 1930s. It comprises of more than 30000 tablets (fragmentary or entire) that were written in the period 509-494 BCE (at the time of Darius I). The tablets were written in Susa and other parts of Fars and the territory of the ancient kingdom of Elam that vanished in the middle of the 7th c. (more than 130 years before these texts were written). Around 50 texts had Aramaic glosses. More than 2000 tablets have been published and translated. These texts are records of transactions, distribution of food, provisioning of workers, transportation of commodities, etc.; few tablets were written in other languages, namely Old Iranian (1), Babylonian (1), Phrygian (1) and Greek (1).

The Persepolis Treasury Archive was found in the northeastern room of the Treasury of Xerxes. It contains more than 750 tablets and fragments (in Elamite) and more than 100 have been published. They all date back in period 492-458 BCE. These tablets are either letters or memoranda dispatched by imperial officials to the head of the Treasury; they concern the payment of workmen, the issue of silver, and other administrative procedures. Only one tablet was written in Babylonian.

The entire documentation offers valuable information as regards the function of various imperial services, namely the couriers, the satraps, the imperial messengers, the imperial storehouse, etc. The archives shed light on the origin of the imperial administrators, as ca. 1900 personal names have been recorded: 10% were Elamites (who had apparently survived for long far from their country after the destruction of Susa by Assurbanipal (640 BCE), fewer were Babylonians, and the outright majority consisted of Iranians (Persians, Medes, Bactrians, Sakas, Arians, etc.).

C. Imperial Aramaic

The diffusion of the use of Aramaic started already in the Neo-Assyrian times and during the 7th c. BCE; the creation of the 'Royal Road', the systematization of the transportation, the improvement of communications, and the formation of the network of land-, sea- and desert routes that we now call 'Silk-, Spice- and Perfume- Road' during the Achaemenid times helped further expand the use of Aramaic. The linguistic assimilation of the Babylonians, the Jews and the Phoenicians with the Aramaeans only strengthened the diffusion of the Aramaic, which became the second international language ('lingua franca') in the History of the Mankind (after the Akkadian / Assyrian-Babylonian). Gradually, Aramaic became an official Achaemenid language after the Old Achaemenid Iranian.

Except the Aramaic texts attested in the Persepolis Administrative Archives, thousands of Aramaic texts of the Achaemenid times shed light onto the society, the economy, the administration, the military organization, the trade, the religions, the cults, the culture and the spirituality attested in various provinces of the Iranian Empire. At this point, only indicatively, I mention few significant groups of texts:

- the Elephantine papyri and ostraca (except Aramaic, they were written in Hieratic and Demotic Egyptian, Coptic, Alexandrian Koine, and Latin) – 5th and 4th c. BCE,

- the Hermopolis Aramaic papyri,

- the Padua Aramaic papyri, and

- the Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents from Bactria (48 texts written on leather, papyrus, stone or clay, dating from the period 353-324 BCE, and mainly from the reign of Artaxerxes III whereas the most recent dates from the reign of Alexander the Great).

Here I have to add that the widespread use of Imperial Aramaic and its use as a second official language for Achaemenid Iran brought an end to the use of the Elamite (in the middle of the 5th c.) and, after the end of the Achaemenid dynasty and the split of the state of Alexander the Great, contributed to the formation of two writing systems, namely Parthian and Pahlavi which were in use during the Arsacid and the Sassanid times. Imperial Aramaic helped establish many other writing systems, but this goes beyond the limits of the present seminar.

3- Problems of historiography continuity

There are no historical references to the Achaemenid dynasty made at the time of the Arsacids (Ashkanian: 250 BCE-224 CE) and the Sassanids 224-651 CE); this situation is due to many factors:

- the prevalence of another Iranian nation of probably Turanian origin, namely the Parthians and the Arsacid dynasty,

- the rise of the anti-Achaemenid, anti-Zoroastrian Magi who tried to impose Mithraism throughout Iran during the Arsacid times,

- the formation of an oral epic tradition and the establishment of a legendary historiography about the pre-Arsacid past during the Sassanid times, and

- the scarcity of written sources and the terrible destructions that occurred in Iran during the Late Antiquity, the Islamic era, and the Modern times (early Islamic conquests, divisions of the Abbasid times, Mongol invasions, Safavid-Ottoman wars, Western colonial looting, etc.).

This situation raised Western academic questions of Iranian identity, continuity, and historicity. But this attempt is futile. Iranian historiography of Islamic times shows that these questions were fully misplaced.

4- Iranian posterior historiography (Iranian historiography of Islamic times)

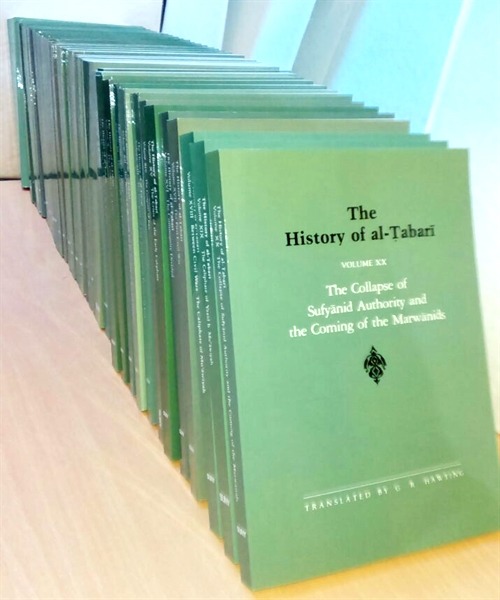

With Tabari (839-923) and his voluminous History of Prophets and Kings we realize that there were, in spite of the destructions caused because of the Islamic conquests, historical documents on which he was based to expand about the Sassanid dynasty; actually one out of the 40 volumes of the most recent translation of Tabari to English (published by the State University of New York Press from 1985 through 2007) is dedicated to the History of Sassanid Iran (vol. 5). And the previous volume (vol. 4) covers the History of Achaemenid and Arsacid Iran, Alexander the Great, Nabonid Babylonia, Assyria and Ancient Israel and Judah.

Other important Iranian historians of the Islamic times, like Abu'l-Fadl Bayhaqi (995-1077), Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247-1318) who wrote the truly first World History, Alaeddin Aṭa Malik Juvaynī (1226-1283), and Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi (ca. 1370-1454), did not expand much on pre-Islamic periods as the focus of their writing was on contemporaneous developments.

However, the aforementioned historians and all the authors, who are classified in this category, represent only one dimension of Iranian historiography of Islamic times. A totally different approach and literature have been illustrated by Ferdowsi's Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Abu 'l Qasem Ferdowsi (940-1025) was not the first to compose an epic in order to standardize in mythical terms and legendary concepts the pre-Islamic Iranian past; but he was the most successful and the most illustrious. That is why many other epic poets followed his example, notably the Azeri Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209) and the Turkic Indian Amir Khusraw (1253-1325).

Within the context of this poetical historiography, historical emperors of pre-Islamic Iran appear as legendary figures only to be then viewed as materialization of divine patterns. The origin of this transcendental historiography seems to be retraced in the Sassanid times, but all the major themes are clearly of Zoroastrian identity and can therefore be attributed to the Achaemenid world perception and world conceptualization.

It is essential at this point to state that, until the imposition of modern Western colonial academic and educational standards in Iran, Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and the corpus of Iranian legendary historiography was the backbone of the Iranian cultural, intellectual and educational identity.

It is a matter of academic debate whether an original text named Khwaday-Namag, written during the Sassanid times, and now lost, is at the very origin of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and of the Iranian legendary historiography. The 19th c. German Orientalist Theodor Nöldeke is credited with this theory that has not yet been proved.

All the same, the spiritual standards of this approach are detected in the Achaemenid times.

5- Foreign historiography

Ancient Greek (in reality, Ionian and Attic), Ancient Hebrew and Latin sources of Achaemenid History exist, but first they are external, second they appear to be posterior in their largest part, and third they often bear witness to astounding inaccuracies, fables, untrustworthy data, misplaced focus, excessive verbosity without real substance, and -above all- an enormous and irreconcilable misunderstanding of the Iranian Achaemenid reality, values, world view, mindset, and behavior.

The Ancient Hebrew sources shed light on issues that were apparently critical to the tiny and unimportant, Jewish minority of the Achaemenid Empire; however, these Biblical narratives concern facts that were absolutely insignificant to the imperial authorities of Parsa. One critical issue is concealed by modern scholars though; although all the nations of the Empire were regularly mentioned in the Achaemenid inscriptions and depicted on bas reliefs, the Jews were not. This undeniable fact irrevocably conditions the supposed 'importance' of Biblical texts like Ezra, Esther, Nehemiah, etc. All the same, these foreign historical sources are important for the Jews.

The Ionian and Attic accounts of events that were composed by the Carian renegade Herodotus, the Dorian Ctesias, and the Athenian Xenophon present an even more serious problem. They happened to be for many centuries (16th – 19th c.) the bulk of the historical documentation that Western European academics had access to as regards Achaemenid Iran. This situation produced grave biases among Western academics, because they took all these sources at face value since they had no access to original documentation. The grave trouble persisted even after the decipherment of the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing and the archaeological excavations that brought to daylight original Iranian imperial documentation.

Only recently, at the end of the 20th c., leading Iranologists like Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg started criticizing the absolutely delusional History of Achaemenid Iran that modern Western scholars were producing without even understanding it by foolishly accepting Ancient Ionian myths, lies and propaganda against the Iranian Empire at face value. This grave problem had also two other parameters:

- first, there was an enormous gap of civilization and a tremendous cultural difference between the Iranian imperial world view, the spiritual valorization of the human being, and the Zoroastrian monotheism from one side and the chaotic, disorderly and profane elements of the western periphery of the Empire. The so-called Greek tribes in Western Anatolia and in the South Balkans were not only multi-divided and plunged in permanent conflict; they were also extremely verbose on common issues, they desecrated the divine world with their nonsensical myths and puerile narratives, and they defiled human spirituality with their love stories about their pseudo-gods. But, very arbitrarily and quite disastrously, the so-called Ancient Greek civilization had been erroneously taken as 'classics' by modern Europeans at a time they had no access to Ancient Oriental sources.

- second, the vertical differentiation between Imperial Iran as the blessed land of divine mission and the disunited and peripheral lands of conflict, discord and strife that were inhabited by the Greek tribes was reflected on the respective, impressively different types of historiography; to the Iranians, few words written by anonymous scribes were enough to describe the groundbreaking deeds of divinely appointed rulers. But for the Greeks, the useless rumors, the capricious hearsay, the intentional lie, the nefarious expression of their complex of inferiority, the vicious slander, and the deliberate ignominy 'had' to be recorded and written down.

The fact that Herodotus' and Xenophon's long narratives have long been taken as the basic source of information about Achaemenid Iran demonstrates how disoriented and misplaced modern Western scholarship is. But by preferring to rely mainly on the Ancient Greek lengthy and false narratives, and not on the succinct, true and chaste Old Achaemenid Iranian inscriptions, they totally misrepresent Ancient Iranian History, preposterously extrapolating later and corrupt standards to earlier and superior civilizations.

And whereas Ancient Roman authors, who wrote in Latin (Pliny the Elder, Seneca the Younger, etc.), and Jewish or Christian historians, who wrote in Alexandrine Koine, like Flavius Josephus and Eusebius of Caesarea Maritima, reproduced the style of lengthy narratives that turns History to mere gossip, the great Babylonian scholar Berossus was very reluctant to add personal comments to his original sources or to allow subjective considerations and thoughts to contaminate his text.

In any case, the vast issue of the multilayered damages caused by the untrustworthy Ancient Greek historiography to modern Western academics' perception and interpretation of Achaemenid Iran is a topic that deserves an entirely independent seminar.

--------------

To watch the video (with more than 110 pictures and maps), click the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN - Achaemenid beginnings 1Α

By Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

------------------------

To listen to the audio, clink the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN - Achaemenid beginnings 1 (a+b)

------------------------------

Download the text in PDF:

The Villa des Orangers, luxury five star hotel is located in the heart of Marrakech and is a true haven of peace. Everything has been carefully chosen to make your stay relaxing and sophisticated: an elegant decoration, delicious cuisine with Mediterranean and Moroccan flavours, a large garden and lush courtyards, three swimming pools, a traditional Moroccan Hammam, massage rooms, beauty salon, fitness, an open bar to enjoy a mint tea with Moroccan pastries during the day.

Nubianization of the Cushites, Linguistic Denigration of Berbers, Denial of Hamitic Identity

Nubianization of the Cushites, Linguistic Denigration of Berbers, Denial of Hamitic Identity: the Next Genocide in Africa

By Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Speaking at the 5th Annual Conference of the Network of Oromo Studies (NOS), which took place on 27th February 2021 on Visual Technology, I exposed one more Western colonial distortion, falsification and machination; the title of my speech was: "Fake Nubia: a Colonial Forgery to deprive Cushitic Nations from National Independence, Historical Identity and Cultural Heritage".

The text of my contribution was published without the notes here:

I herewith publish the first two notes of my speech; they constitute a brief but direct denunciation of the major Western anti-African forgeries, namely

- the Nubianization of the East African Cushites and of their historical past and heritage,

- the disparagement of the Berbers, and

- the denial of the existence of the Hamites.

Although short, this text provides readers with a comprehensive insight into the evil, racist and systematic efforts of distortion of the African past by the Anglo-French and the American criminal fraudsters and biased pseudo-academics.

-----------------------------------------

Read and download the 3000-word text here:

and

François Bocion - Venice at sunset (1874)

Χούνζα, Μπαλτί, Ισλάμ, Βουδισμός, οι Στρατιώτες του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου κι οι Δρόμοι του Μεταξιού, των Μπαχαρικών και των Λιβανωτών

Hunza Valley, Baltistan, Islam, Buddhism, Alexander the Great's soldiers, and the Silk-, Spice-, and Incense Roads

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 8η Μαΐου 2019.

Ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης ανασυνθέτει υλικό από πρότερες δημοσιεύσεις μου για τους Δρόμους του Μεταξιού και στοιχεία από ομιλία μου σχετικά με τους Δρόμους των Λιβανωτών και των Μπαχαρικών ανάμεσα στο Κέρας της Αφρικής και την Κεντρική Ασία, την οποία έδωσα στο Καζακστάν τον Ιανουάριο του 2018.

----------------------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/05/08/χούνζα-μπαλτί-ισλάμ-βουδισμός-οι-στρ/ ==================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Κοντά στα σύνορα με την Κίνα, στο βόρειο άκρο του Πακιστάν και τριγύρω από το Γκιλγκίτ, πολλές μικρές κοιλάδες κατοικούνται από διαφορετικά μικρά έθνη με μεγάλη Ιστορία και μεγαλύτερο ηρωϊσμό.

Οι Δρόμοι του Μεταξιού, των Μπαχαρικών και των Λιβανωτών δεν περνούσαν πάντοτε από εδώ. Στην εντελώς αρχική τους μορφή, οι εμπορικοί δρόμοι ξεκινούσαν από την Μεσοποταμία και κατέληγαν στην Κίνα και στην Ινδία: επρόκειτο για διαφορετικούς δρόμους.

Και η Μεσοποταμία, αν και μακρύτερα, ήταν πολύ πιο νωρίς συνδεδεμένη με την Κίνα, επειδή πολιτισμός στην Ινδία (ακόμη κι ο πρώιμος, μη ινδοευρωπαϊκός ‘πολιτισμός της Κοιλάδας του Ινδού’) είναι μία πολύ καθυστερημένη περίπτωση, αν πάρουμε ως μέτρα και σταθμά την Σουμέρ, το Ελάμ, την Ακκάδ, την Ασσυρία και την Βαβυλώνα.

Επίσης, στην αρχική μορφή των εμπορικών δρόμων, το Μετάξι δεν ήταν ένα από τα προϊόντα. Αλλά πολύτιμοι λίθοι, σπάνια ορυκτά, μπαχαρικά και λιβανωτά ήταν πάντοτε στο επίκεντρο του εμπορικού ενδιαφέροντος.

Η πραγματική ‘επανάσταση’ στους εμπορικούς δρόμους ανάμεσα στην Μεσοποταμία, την Κίνα και την Ινδία έγινε στα αχαιμενιδικά χρόνια (550-330 π.Χ.) και κυρίως χάρη στην τεράστια σημασία που έδωσαν οι πρώτοι σάχηδες του Ιράν να εγκαθιδρύσουν ένα πολύ σύνθετο σύστημα αυτοκρατορικών οδών, πολύ καλά οργανωμένων, επιμελημένων και προστατευμένων, διά ξηράς, ερήμου και θαλάσσης.

Το μεγάλο αυτό συγκοινωνιακό και εμπορικό δίκτυο προσέφερε πολλές εναλλακτικές δυνατότητες: αντί να στείλουν προϊόντα, αποστολές, στρατό, κοκ από την Αίγυπτο (ιρανική αχαιμενιδική σατραπεία) διά ξηράς στο Φαρς (κεντρική επαρχία του Ιράν), δηλαδή μέσω Παλαιστίνης, Συρίας, Μεσοποταμίας και Ελυμαΐδας (: Νότιας Υπερτιγριανής), μπορούσαν να τα στείλουν από τα αιγυπτιακά λιμάνια της Ερυθράς Θαλάσσης στον Περσικό Κόλπο.

Ο Δαρείος Α’, προνοητικός, άνοιξε εκ νέου την από αιώνες κλεισμένη, αρχαία διώρυγα του Σουέζ, η οποία ήταν ολότελα διαφορετικής κατεύθυνσης από την σύγχρονη (δηλαδή από τα δυτικά προς τα ανατολικά) και συνέδεε τον Νείλο (από την περιοχή περίπου του σημερινού Καΐρου) με την Ερυθρά Θάλασσα.

Κάτι ακόμη πιο σημαντικό που επιτεύχθηκε από την αχαιμενιδική ιρανική εμπορική και συγκοινωνιακή κοσμογονία ήταν το γεγονός ότι διαφορετικοί εμπορικοί δρόμοι αλληλεξαρτήθηκαν για πρώτη φορά, έτσι καθιστώντας γνωστά σε πολύ μακρινά σημεία πολλά προϊόντα μέχρι τότε άγνωστα.

Το εμπόριο μεταξύ Μεσοποταμίας και Κίνας, ή Μεσοποταμίας και Ινδίας (: Κοιλάδας του Ινδού) ανάγεται εύκολα στην 3η προχριστιανική χιλιετία στα τέλη της οποίας βλέπουμε ένα πλήθος διαδοχικών αρχαιολογικών χώρων να χαράσσουν μια γραμμή που μέσω Κεντρικής Ασίας συνέδεε την κοιλάδα των Διδύμων Ποταμών (Τίγρη κι Ευφράτη) με την κοιλάδα του Κίτρινου Ποταμού. Αλλά η Αίγυπτος ελάχιστα επωφελήθηκε των ασσυροβαβυλωνιακών εμπορικών δρόμων κι ανταλλαγών.

Από την άλλη, η Αίγυπτος είχε ήδη από τα τέλη της 3ης προχριστιανικής χιλιετίας διαμορφώσει ένα μεγάλο εμπορικό δίκτυο διά του Αρχαίου Βασιλείου του Κους (: Αιθιοπίας, δηλαδή του σημερινού Σουδάν) με την Σαχάρα, διά της Λιβύης με τον Άτλαντα, και διά της Ερυθράς Θαλάσσης με το ανεξάρτητο σομαλικό βασίλειο του Πουντ στην ανατολική ακτή της Αφρικής πέρα από το Κέρας της Αφρικής. Αλλά η Ασσυρία κι η Βαβυλώνα ελάχιστα επωφελήθηκαν των αιγυπτιακών εμπορικών δρόμων κι ανταλλαγών.

Όμως στα αχαιμενιδικά χρόνια, όλα αυτά τα εμπορικά δίκτυα αναμείχθηκαν και αλληλοσυνδέθηκαν σε ένα μείζον εμπορικό και συγκοινωνιακό δίκτυο από τον Αφρικανικό Άτλαντα μέχρι τα ανατολικά παράλια της Ασίας.

Η πρώτη παγκοσμιοποίηση ήταν γεγονός.

Ήταν απλώς θέμα χρόνου πάνω στους εμπορικούς δρόμους αυτούς να μην μετακινούνται μόνον προϊόντα αλλά επίσης γραφές, γλώσσες, θρησκείες, λατρείες, πίστεις, κοσμογονίες, θεουργίες, μυστήρια και μυστικά κυκλώματα.

Μια πρώιμη μετακίνηση ήταν αυτή του εκδιωκόμενου από την Βόρεια Ινδία Βουδισμού προς τις ανατολικές επαρχίες του αχαιμενιδικού Ιράν ήδη τον 6ο – 5ο προχριστιανικό αιώνα.

Σ’ αυτό βοήθησε πολύ η θρησκευτική ανοχή που επικρατούσε στην αχανή αυτοκρατορία που ξεκινούσε από τα σύνορα της Ινδίας με το Πακιστάν κι έφθανε στο Αιγαίο, ενώ είχε συνενώσει όλες τις εκτάσεις από το Ουζμπεκιστάν και την νότια Ουκρανία μέχρι το Σουδάν και το Ομάν.

Από το ανατολικό αχαιμενιδικό Ιράν (δηλαδή τις εκτάσεις των σημερινών Πακιστάν, Αφγανιστάν κι Ουζμπεκιστάν), ο Βουδισμός διαδόθηκε αργότερα προς την Κεντρική Ασία κι έγινε μια από τις πολλές θρησκείες που πολλά τουρανικά έθνη αποδέχθηκαν. Από εκτάσεις της Κεντρικής Ασίας (του σημερινού Καζακστάν και Ανατολικού Τουρκεστάν, δηλαδή της βορειοδυτικής επαρχίας Σινκιάν της Κίνας) διαδόθηκε αργότερα ο βουδισμός στην καθαυτό Κίνα.

Το ίδιο εμπορικό δίκτυο συνέχισε να λειτουργεί μετά την εκ μέρους του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου κατάληψη της αχαιμενιδικής αυτοκρατορίας και ανάληψη καθηκόντων σάχη και συνεπώς εγγυητή και συνεχιστή της αυτοκρατορικής παράδοσης.

Το ίδιο συνέβηκε και στα χρόνια των Επιγόνων παρά τους διάφορους πολέμους που οι ίδιοι δεν έπαυσαν να κάνουν.

Με τους Αραμαίους να ελέγχουν το διά ξηράς και δι’ ερήμου εμπόριο και με τους Υεμενίτες (οργανωμένους στα ανεξάρτητα και πολύ εύπορα βασίλεια Καταμπάν, Χιμυάρ, Σαβά και Χαντραμάουντ) να ασκούν μια σχεδόν αποκλειστική θαλασσοκρατορία στην Ερυθρά Θάλασσα και στον Ινδικό Ωκεανό (μέχρι την Ινδοκίνα και την Ινδονησία), η αλληλεξάρτηση των συμβαλλομένων μερών εντάθηκε.

Η σύσταση από Χαλδαίους Αραμαίους εμπόρους της Γέρρας, της πόλης με τα αλάτινα τείχη, στα δυτικά παράλια των συγχρόνων Εμιράτων, δυτικά του Αμπού Δάμπι, ήταν ένα κοσμοϊστορικό γεγονός.

Οι Χαλδαίοι έμποροι που ίδρυσαν την μεγαλύτερη εμπορική πόλη του κόσμου ανατολικά της Αλεξάνδρειας ήξεραν πάρα πολύ καλά τι έκαναν: εκμεταλλευόμενοι την σχετική αδυναμία του παρθικού αρσακιδικού κράτους του Ιράν βρήκαν ένα κομβικό σημείο από όπου περνούσε ένα μεγάλο τμήμα του εμπορίου μεταξύ Δύσης κι Ανατολής και θεμελίωσαν εκεί μια πόλη-εμπορείο που μπορούσε να θησαυρίσει και από το εμπόριο μεταξύ Νότου και Βορρά.

Η Γέρρα – στην οποία αναφέρονται ο Πτολεμαίος Γεωγράφος, ο Στράβων κι ο Πλίνιος – προσέφερε στην Κίνα ανατολικό αφρικανικό εμπόρευμα το οποίο, αντί να περιπλέει την Ινδία και την Νότια Ασία, διοχετευόταν από την Υεμένη στα νότια παράλια του Περσικού Κόλπου κι από κει προς την Κεντρική Ασία, εκτός των συνόρων του Ιράν έτσι αποφεύγοντας δασμούς.

Με τον τρόπο αυτό όμως ενισχύθηκαν φυγόκεντρες τάσεις στο Ιράν και συστάθηκαν ανατολικά ιρανικά και τουρανικά κράτη, όπως το ινδοπαρθικό κράτος με πρωτεύουσα την Μινναγάρ και επίνειο το Βαρβαρικόν (κοντά στο σημερινό Καράτσι) και το Κουσάν με πρωτεύουσα την Καπίτσα (κοντά στην Καμπούλ) που ήταν τρόπον τινά μια συνέχεια του βασιλείου της Βακτριανής.

Τότε ανοίχθηκε για πρώτη φορά (κατά τον πρώτο προχριστιανικό αιώνα) ο εμπορικός δρόμος που συνέδεε την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού με την Γιαρκάντ και το Χοτάν στα νότια άκρα του Ανατολικού Τουρκεστάν.

Φυσικό ήταν να ακολουθήσει ένα νέο στάδιο διάδοσης του Βουδισμού από τις ανατολικές ιρανικές επαρχίες (ή αυτονομημένα βασίλεια) προς την Κεντρική Ασία και αυτό να ακολουθήσει τον νέο αυτό δρόμο. Λίγο αργότερα, από κει (όπως και από αλλού) θα περνούσαν ο Μανιχεϊσμός και το Ισλάμ.

Ανάμεσα στους Χούνζα σήμερα έχει επικρατήσει το Ισλάμ αλλά ανάμεσα στους Μπουρούσο του Μπαλτιστάν υπάρχουν ακόμη βουδιστές.

Ο εξισλαμισμός των Μπαλτί ήταν υπόθεση 15ου – 16ου αιώνα. Όμως οι Χούνζα αποδέχθηκαν το Ισλάμ νωρίτερα. Αλλά το αίμα των απογόνων των στρατιωτών του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου έβραζε στις φλέβες τους μέχρι πρόσφατα.

Αν και ελάχιστοι τον αριθμό, πριν από 400 χρόνια οι Μιρ (ισλαμικός περσικός τίτλος κατ’ αποκοπήν από το αραβικό εμίρ/εμίρης) των Χούνζα αναγνώριζαν το μικροσκοπικό κράτος τους και την Κίνα ως τα ισχυρώτερα κράτη στον κόσμο!

Η διασπορά των απογόνων των Επιγόνων ήταν μεγάλη αλλά μετά από αρκετές γενεές, είτε είχαν αποδεχθεί τον Βουδισμό, είτε πίστευαν σε διάφορες μορφές ανατολικών Μιθραϊσμών, είτε είχαν ασπασθεί τον αρσακιδικό ζενδισμό (που ήταν μια ηθική ερμηνεία της ζωροαστρικής μεταφυσικής), όλοι τους αποτελούσαν τμήμα των ανατολικών πολιτισμών, παιδείας και παραδόσεων.

Η φυλετική αναγωγή τους στους στρατιώτες του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου δεν είχε κανένα ρατσιστικό ή εθνικιστικό χαρακτήρα επειδή δεν υπήρχε κάτι τέτοιο στην Αρχαιότητα.

Ήταν θέμα ηθικής, πολιτισμικής κι εσχατολογικής διάστασης γι’ αυτούς και οι στρατιωτικές επιτυχίες του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου ήταν ένα ολότελα ασήμαντο σημείο αναφοράς μπροστά στο ψυχικό έργο του και στον μυθικό, μεσσιανικό κι αποκαλυπτικό συμβολισμό του έργου του.

Ήταν συνεπώς φυσιολογικό για τους τελευταίους ελληνόφωνους απογόνους των Επιγόνων να αναμειχθούν με διαφορετικά κατά τόπους έθνη, επειδή η φυλετική – εθνική υπόστασή τους ήταν για τους ίδιους ολότελα ασήμαντη μπροστά στην ένταξή τους σε ένα Θείο Έργο ψυχικών διαστάσεων και κοσμοϊστορικής σημασίας που είχαν ήδη επιτελέσει οι πρόγονοί τους μαζί με τον Μεγάλο Αλέξανδρο – ένα έργο-προτύπωση του Έργου του Μεγάλου Βασιλέα (Αποκάλυψη ΙΔ’ 14) στο Πλήρωμα του Χρόνου.

Αυτό το Έργο πρώτος κατέγραψε σε ελληνικά στον Βίο Αλεξάνδρου ο ανώνυμος συγγραφέας που αποκαλείται Ψευδο-Καλλισθένης επειδή δεν σχετίζεται με τον γνωστό ιστορικό.

Για τους τελευταίους ελληνόφωνους απογόνους των Επιγόνων η Μόνη Αλήθεια κι Αξία στα ανθρώπινα πράγματα ήταν ο Μύθος – κι όχι ο σατανικός κι απάνθρωπος ‘Λόγος’.

Κι έτσι στον Μύθο αποτυπώθηκε όλη η ουσία του κορυφαίου έργου του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου που μόνον σημερινοί κρετίνοι ψάχνουν να βρουν σε ‘στρατιωτικές κατακτήσεις’ και σε ψέμματα περί ‘εκπολιτισμού άλλων εθνών’.

Μυούμενος ο Αλέξανδρος σε ανατολικά μυστήρια, στην Αίγυπτο, στην Περσία, και στην Βαβυλώνα, εκπολιτίσθηκε ο ίδιος κι έγινε Μεγάλος.

Και γι αυτό σήμερα βρίσκουμε την αναφορά στους στρατιώτες του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου σε πολλά και διαφορετικά έθνη που μιλάνε ολότελα διαφορετικές γλώσσες και πιστεύουν ολοσχερώς αντίθετες θρησκείες, και όμως θεωρούν εαυτούς απογόνους των στρατιωτών του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου. Οι Καλάς και οι Χούνζα του βόρειου Πακιστάν είναι μόνον ένα μικρό παράδειγμα. Θα χρειαζόταν μια ολόκληρη εγκυκλοπαίδεια για να καταγραφούν μικρές και μεταξύ τους διαφορετικές πληθυσμιακές ενότητες που ανάγουν την καταγωγή τους στους στρατιώτες του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου.

Σημεία της ορεινής γης των Χούνζα και των Μπαλτί

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Форт Балтит в долине Хунзы: маленький Тибет на севере Пакистана

https://ok.ru/video/1362004609645

Baltit Fort in Hunza Valley: a Small Tibet in Northern Pakistan

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240158

Κάστρο Μπαλτίτ στην Κοιλάδα Χούνζα: ένα Μικρό Θιβέτ στο Βόρειο Πακιστάν

Περισσότερα:

Baltit Fort is situated in Karimabad, once was capital of the state of Hunza, now Tehsil Headquarter of District Gilgit. It is approached by Karakuram Highway from Gilgit, the capital of Northern Areas, Pakistan. The Baltit Fort stands on a artificially flattened spur below the Ulter Glacier. Strategically located with a commanding view of the Hunza Valley and its tributaries, its inhabitants controlled the seasonal trans-Karakuram trade between south and Central Asia. The Baltit Fort is rectangular in plan with three floors and stands on a high stone plinth Fig-I. Whilts the ground floor consist mainly of storage chambers, the first floor is oriented around as open hall.

A staircase leads to the second floor which was mainly used during the winter months and contains an audience hall, guest room, dining hall, kitchen and servants quarters. A further staircases leads up to the third floor, which is partly open to the elements and contains the summer dining room, audience chamber, bedroom and reception hall. Inhabited by the Mir, or ruler of Hunza until 1945.

The conservation work carried out in the 1990 indicated that the core of the structures, a single defensive timber and stone tower, had been built in the eight century A.D. This tower was augmented by additional towers and linked by a single story construction consisting of small rooms and sub-surface storage chambers. The complex was then later expanded by the addition of a second, and then a third floor. The structure’s stone walls, built in an area of frequent seismic movements, were provided with a traditional internal framework of timber for greater stabilisation. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1882/

Also: Baltit Fort (Urdu: قلعہ بلتت) is a fort in the Hunza valley, near the town of Karimabad, in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of northern Pakistan. Founded in the 8th CE, it has been on the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative list since 2004. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltit_Fort and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cultural_heritage_sites_in_Gilgit-Baltistan

————————————————————–

Σχετικά με τους Χούνζα και τους Μπαλτί:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunza_Valley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mir_of_Hunza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hunza_(princely_state)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burushaski

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burusho_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baltistan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balti_people

Σχετικά με την διάδοση του Βουδισμού στο Πακιστάν, Ιράν, Κεντρική Ασία και Κίνα:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_in_Pakistan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kargah_Buddha

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gondrani

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_in_Central_Asia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharmaguptaka

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gandh%C4%81ran_Buddhist_texts

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarvastivada

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mulasarvastivada

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk_Road_transmission_of_Buddhism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk_Road_transmission_of_Buddhism#Central_Asian_missionaries

https://studybuddhism.com/en/tibetan-buddhism/about-buddhism/the-world-of-buddhism/spread-of-buddhism-in-asia

http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/artl/buddhism.shtml

http://www.silk-road.com/artl/buddhism.shtml

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_in_Iran

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/buddhism-i

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137022943_2

——————————————-

According to a Buddhist legend preserved in Pali (an ancient Prakrit language, derived from Sanskrit, which is the scriptural and liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism), the first instance of Buddhism entering Iran seems to have been during the life of the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni (roughly 5/6th century BCE.

The legend speaks of two Merchant brothers from Bactria (modern day Afghanistan) who visited the Buddha in his eighth week of enlightenment, became his disciples and then returned to Balkh (major city of Bactria) to build temples dedicated to him.

Whatever the historical validity of this story, there is strong evidence to show that Balkh did become a major Buddhist region and remained so up until the Arab Muslim invasion of the 7th century.

http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/non-iranian/buddhism_iran.htm

-------------------------

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/ss-250645898

https://issuu.com/megalommatis/docs/hunza_balti_islam_buddhism_alexander_the_great

https://vk.com/doc429864789_620740190

https://www.docdroid.net/9CAJCUX/xounza-mpalti-islam-boydismos-oi-stratiwtes-toy-meghaloy-aleksandroy-ki-oi-dromoi-toy-metaksiou-docx

Bābur, Pādishāh of Hindustan

unknown court painter 1630

Victoria & Albert Museum

Born in 1483, Bābur was the founder of the Mughal Empire, which he ruled as Great King between 1526 and his relatively early death in 1530, after rising from the governorship of remote Fergana (present-day Uzbekistan, then part of the Timurid Empire) and conquering the lands of the Arghun (including Kabul) and the Delhi Sultanate, as well as capturing Samarkand and forcing Mewar (present-day northern India) into vassalage. He was a fifth-generation agnatic descendant of Timur and a 14th-generation cognatic descendant of Genghis Khan.

Οι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν (Σιρβάν-σαχ) και το Ανάκτορό τους στο Μπακού του Αζερμπαϊτζάν

The Shahs of Shirvan (Shirvanshahs) and their Palace in Baku, Azerbaijan

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 2η Σεπτεμβρίου 2019.

Ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης αναπαράγει τμήμα διάλεξής μου στο Πεκίνο τον Ιανουάριο του 2018 για τα υπαρκτά και τα ανύπαρκτα έθνη του Καυκάσου, την ιστορική συνέχεια πολιτισμικής παράδοσης, την ιστορική ασυνέχεια ορισμένων διεκδικήσεων, καθώς και την σωστή κινεζική πολιτική στον Καύκασο. Στο σημείο αυτό, η ιστορική συνέχεια της προϊσλαμικής Ατροπατηνής στο ισλαμικό Αζερμπαϊτζάν καθιστά ταυτόχρονα το Αζερμπαϊτζάν "Ιράν" και το Ιράν "περιφέρεια του Αζερμπαϊτζάν".

---------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/09/02/οι-σάχηδες-του-σιρβάν-σιρβάν-σαχ-και-τ/ ================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Η περιοχή του Σιρβάν είναι το κέντρο του σημερινού Αζερμπαϊτζάν και ονομαζόταν έτσι από τα προϊσλαμικά χρόνια, όταν ο όλος χώρος του Αζερμπαϊτζάν και του βορειοδυτικού Ιράν ονομαζόταν Αδουρμπαταγάν, λέξη από την οποία προέρχεται η ονομασία του σύγχρονου κράτους και η οποία αποδόθηκε στα αρχαία ελληνικά ως Ατροπατηνή.

Το Σιρβάν βρισκόταν στα βόρεια όρια του ιρανικού κράτους και, όταν αυτό βρισκόταν σε κατάσταση παρακμής, αδυναμίας και προβλημάτων, συχνά ντόπιοι Ατροπατηνοί ηγεμόνες σχημάτιζαν μια ανεξάρτητη τοπική αρχή. Συνεπώς, ο τίτλος ‘Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν’ ανάγεται ήδη σε προϊσλαμικά χρόνια και μουσουλμάνοι ιστορικοί μας πληροφορούν ότι ένας ‘Σάχης του Σιρβάν’ προσπάθησε να ανακόψει εκεί τα επελαύνοντα ισλαμικά στρατεύματα τα οποία στα μισά του 7ου αιώνα έφθασαν και εκεί, όταν κατέρρευσε το σασανιδικό Ιράν. Το γιατί είχε το Σιρβάν γίνει ανεξάρτητο βασίλειο σε χρονιές όπως 630 ή 650 μπορούμε να καταλάβουμε πολύ εύκολα.

Οι συνεχείς εξουθενωτικοί πόλεμοι Ρωμανίας και Ιράν (601-628), και η αντεπίθεση του Ηράκλειου με σκοπό να αποσπάσει τον Τίμιο Σταυρό από τον Χοσρόη Β’ και να εκδιώξει τους Ιρανούς από την Αίγυπτο και την Συρο-Παλαιστίνη είχαν ήδη ολότελα εξαντλήσει και τις δύο αυτοκρατορίες πριν εμφανιστούν στον ορίζοντα τα στρατεύματα του Ισλάμ.

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν στο Μπακού

Το Σιρβάν καταλήφθηκε από τα ισλαμικά στρατεύματα (που πολεμούσαν υπό τις διαταγές του Σαλμάν ιμπν Ράμπια αλ Μπαχίλι) και μάλιστα αυτά έφθασαν βορειώτερα στον Καύκασο, αλλά στην τεράστια περιοχή που έλεγχε πρώτα το ομεϋαδικό και μετά το 750 το αβασιδικό χαλιφάτο, από την βορειοδυτική Αφρική μέχρι την Κίνα και την Ινδια, το Σιρβάν ήταν και πάλι ένα είδος περιθωρίου: δεν ήταν ούτε καν ένα σημαντικό σύνορο επειδή μετά το Σιρβάν δεν υπήρχε ένα μεγάλο αντίπαλο κράτος.

Αντίθετα, αυτό συνέβαινε ήδη σε άλλες περιοχές όπως στην Ανατολία (Ρωμανία), την Κεντρική Ασία (Κίνα), την Κοιλάδα του Ινδού (το κράτος του Χάρσα), και την Αίγυπτο (χριστιανική Νοβατία και Μακουρία).

Έτσι, αφού το Σιρβάν διοικήθηκε από μια σειρά διαδοχικών απεσταλμένων των χαλίφηδων (όπως για παράδειγμα, στα χρόνια του Αβασίδη Χαλίφη Χαρούν αλ Ρασίντ, ο Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazid_ibn_Mazyad_al-Shaybani), από τις αρχές του 9ου αιώνα οι απόγονοι του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι δημιούργησαν μια τοπική δυναστεία (γνωστή ως Γιαζιντίδες – άσχετοι από τους Γιαζιντί) που ανεγνώριζε την χαλιφατική αρχή της Βαγδάτης.

Ανατολική Μικρά Ασία, Βόρεια Μεσοποταμία, ΒΔ Ιράν και Καύκασος από το 1100 στο 1300

Μετά την αρχή της αβασιδικής παρακμής όμως, στο δεύτερο μισό του 9ου αιώνα, ο εγγονός του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι διεκήρυξε την ανεξαρτησία του από το χαλιφάτο της Βαγδάτης και έλαβε εκνέου τον ιστορικό τίτλο του Σάχη του Σιρβάν. Ο Χάυθαμ ιμπν Χάλεντ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haytham_ibn_Khalid) ήταν λοιπόν ο πρώτος από τους μουσουλμάνους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν.

Γι’ αυτούς χρησιμοποιούνται σήμερα πολλά ονόματα που μπορεί να μπερδέψουν ένα μη ειδικό: Μαζιαντίδες (Mazyadids), Σαϋμπανίδες (Shaybanids), ή όπως προανέφερα Γιαζιντίδες (Yazidids). Αλλά εύκολα μπορείτε να προσέξετε ότι όλα αυτά αποτελούν απλώς διαφορετικές επιλογές συγχρόνων δυτικών ισλαμολόγων και ιστορικών από τα διάφορα ονόματα του ίδιου προσώπου: του Γιαζίντ ιμπν Μαζιάντ αλ Σαϋμπάνι (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazid_ibn_Mazyad_al-Shaybani).

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν κτίσθηκε τον 15ο αιώνα όταν οι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν μετέφεραν την πρωτεύουσά τους από την Σεμάχα (βόρειο Αζερμπαϊτζάν) που είχε καταστραφεί από σεισμούς στο Μπακού. Σχέδιο από: Ismayil Mammad

Αν και αραβικής καταγωγής ως δυναστεία, οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν βρέθηκαν σε ένα κοινωνικό-πολιτισμικό πλαίσιο Αζέρων, Ιρανών και Τουρανών και σταδιακά εξιρανίσθηκαν έντονα κι άρχισαν να παίρνουν ονόματα βασιλέων και ηρώων από το ιρανικό-τουρανικό έπος Σαχναμέ του οποίου η πιο μνημειώδης και πιο θρυλική καταγραφή ήταν αυτή του Φερντοουσί. Έτσι λοιπόν αρχής γενομένης από τον Γιαζίντ Β’ του Σιρβάν (ο οποίος βασίλευσε στην περίοδο 991-1027), οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν είθισται να αποκαλούνται και ως Κασρανίδες (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasranids), επωνυμία που παραπέμπει σε ιρανικά βασιλικά ονόματα επικού και μυθικού χαρακτήρα. Αλλά πρόκειται για την ίδια πάντοτε δυναστεία.

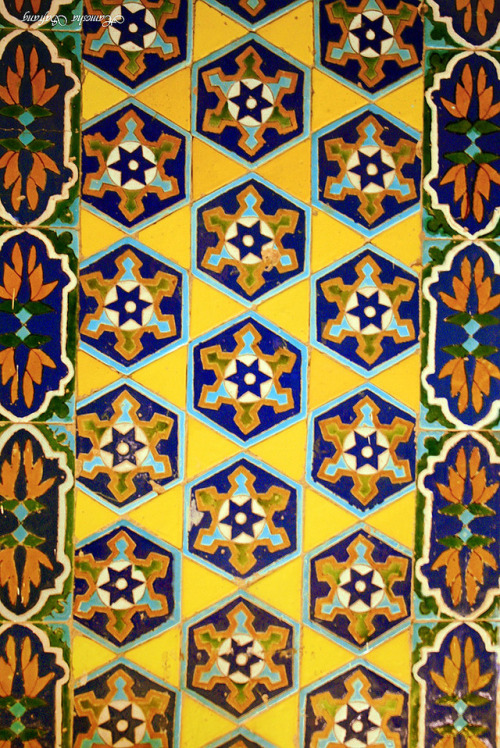

Διακοσμήσεις με αραβουργήματα

Στην συνέχεια, οι μουσουλμάνοι Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν περιήλθαν διαδοχικά σε καθεστώς υποτέλειας προς τους Σελτζούκους, τους Μπαγκρατίδες της Γεωργίας (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagrationi_dynasty), τους Τουρανούς Κιπτσάκ (Kipchak) Ελντιγκουζίδες (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eldiguzids), και τους Μογγόλους Τιμουρίδες.

Όμως η σύγκρουσή τους με τον Τουρκμένο Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ, αρχηγό του τουρκμενικού αιρετικού τάγματος των Σούφι στην περίοδο 1447-1460 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaykh_Junayd), και ο θάνατος του εν λόγω σεΐχη στην μάχη του Χατσμάς (αζερ. Xaçmaz – αγγλ. Khachmaz) δημιούργησαν ένα τρομερό προηγούμενο.

Το μυστικό στρατιωτικό τάγμα των Κιζιλμπάσηδων (το οποίο οργανώθηκε ως στρατιωτική υποστήριξη του μυστικιστικού τάγματος των Σούφι από τον γιο του Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ, Σεΐχη Χαϋντάρ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaykh_Haydar), διατήρησε έντονη μνησικακία προς τους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν, μια σειρά καταστροφικών πολέμων στην ευρύτερη περιοχή του Καυκάσου επακολούθησε κατά την περίοδο 1460-1488, και τελικά και ο Σεΐχης Χαϋντάρ βρήκε και αυτός οικτρό τέλος μαζί με όλους τους στρατιώτες του στην μάχη του Ταμπασαράν (σήμερα στο Νταγεστάν), όπου αντιμετώπισε συνασπισμένους τους Σάχηδες του Σιρβάν και τους Ακκουγιουλού (Τουρκμένους Ασπροπροβατάδες).

Και τελικά το 1500-1501, ο εγγονός του Σεΐχη Τζουνέιντ και γιος του Σεΐχη Χαϋντάρ, Ισμαήλ, επήρε εκδίκηση καταλαμβάνοντας το Σιρβάν και σκοτώνοντας τον Φαρούχ Γιασάρ, τελευταίο Σάχη του Σιρβάν, και την φρουρά του. Επακολούθησε μια βίαιη επιβολή σιιτικών δογμάτων στον τοπικό πληθυσμό και μια απίστευτη τυραννία ως εκδίκηση για την στάση των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν εναντίον των Σιιτών, των Σούφι και των Κιζιλμπάσηδων. Ο Ισμαήλ Α’ ανέτρεψε και το κράτος των Ακκουγιουλού ιδρύοντας την σαφεβιδική (σουφική) δυναστεία του Ιράν.

Η μάχη του Σάχη Ισμαήλ Α’ με τον Φαρούχ Γιασάρ, τελευταίο Σάχη του Σιρβάν από σμικρογραφία ιρανικού σαφεβιδικού χειρογράφου (1501)

Μόνον η νίκη του Σουλτάνου Σελίμ Α’ το 1514 στο Τσαλντιράν εμπόδισε το κιζιλμπάσικο τσουνάμι να καταλάβει όλη την επικράτεια του Ισλάμ.

Η δυναστεία των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν μετά από 640 χρόνια πήρε έτσι ένα τέλος, αλλά έμειναν κορυφαίες δημιουργίες στον τομέα της ισλαμικής τέχνης και αρχιτεκτονικής να μας θυμίζουν την προσφορά της.

Μερικοί από τους μεγαλύτερους επικούς ποιητές, πανσόφους επιστήμονες, και σημαντικώτερους μυστικιστές των ισλαμικών χρόνων, ο Νεζαμί Γκαντζεβί, ο Αφζαλεντίν Χακανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khaqani) και ο Τζαμάλ Χαλίλ Σιρβανί (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nozhat_al-Majales) έζησαν στο Σιρβάν και οι απαγγελίες τους ακούστηκαν στο ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν.

Όμως το τέλος της δυναστείας του Σιρβάν άφησε μέχρι τις μέρες μας μια βραδυφλεγή βόμβα, πολύ καλά κρυμμένη, που κανένας δεν ξέρει σε ποιο βαθμό μας απειλεί όλους ακόμη και σήμερα με ένα απίστευτο αιματοκύλισμα.

Πολλοί προσπάθησαν σε διαφορετικές στιγμές να απενεργοποιήσουνν αυτή την βόμβα και να εξαφανίσουν την απειλή. Ωστόσο και αυτοί στην προσπάθειά τους έχυσαν πολύ αίμα που ακόμη και σήμερα παίζει ένα σημαντικό ρόλο. Η καλά κρυμμένη αυτή απειλή κι ανθρώπινη βόμβα έχει ένα όνομα που θα έπρεπε να κάνει την Ανθρωπότητα να τρέμει:

– Κιζιλμπάσηδες!

Αυτοί είναι οι κυρίαρχοι της αέναης υπομονής και της ατέρμονος προσμονής. Και αν και υπάρχουν πολλές ενδείξεις για τις δραστηριότητές τους, κανένας δεν μπορεί σήμερα να πει αν όντως υπάρχουν και αν διατηρούν την δύναμη που φημίζονταν να έχουν. Για το θέμα μπορούμε να βρούμε μόνον νύξεις κι υπαινιγμούς.

Σ’ αυτό ωστόσο θα επανέλθω. Στην συνέχεια μπορείτε να δείτε ένα βίντεο-ξενάγηση στο Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν και να διαβάσετε σχετικά με τα εκεί μνημεία, την πόλη και την δυναστεία που αποτελεί την ραχοκοκκαλιά της Ισλαμικής Ιστορίας του Αζερμπαϊτζάν. Επιπλέον συνδέσμους θα βρείτε στο τέλος.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Дворец ширваншахов – Shirvanshahs Palace, Baku – Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν

https://www.ok.ru/video/1495285893741

Περισσότερα:

Дворец ширваншахов (азерб. Şirvanşahlar sarayı) — бывшая резиденция ширваншахов (правителей Ширвана), расположенная в столице Азербайджана, городе Баку.

Образует комплекс, куда помимо самого дворца также входят дворик Диван-хане, усыпальница ширваншахов, дворцовая мечеть 1441 года с минаретом, баня и мавзолей придворного учёного Сейида Яхья Бакуви. Дворцовый комплекс был построен в период с XIII[3] по XVI век (некоторые здания, как и сам дворец, были построены в начале XV века при ширваншахе Халил-улле I). Постройка дворца была связана с переносом столицы государства Ширваншахов из Шемахи в Баку.

Несмотря на то, что основные постройки ансамбля строились разновременно, дворцовый комплекс производит целостное художественное впечатление. Строители ансамбля опирались на вековые традиции ширвано-апшеронской архитектурной школы. Создав чёткие кубические и многогранные архитектурные объёмы, они украсили стены богатейшим резным узором, что свидетельствует о том, что создатели дворца прекрасно владели мастерством каменной кладки. Каждый из зодчих благодаря традиции и художественному вкусу воспринял архитектурный замысел своего предшественника, творчески развил и обогатил его. Разновременные постройки связаны как единством масштабов, так и ритмом и соразмерностью основных архитектурных форм — кубических объёмов зданий, куполов, порталов.

В 1964 году дворцовый комплекс был объявлен музеем-заповедником и взят под охрану государства. В 2000 году уникальный архитектурный и культурный ансамбль, наряду с обнесённой крепостными стенами исторической частью города и Девичьей башней, был включён в список Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО. Дворец Ширваншахов и сегодня считается одной из жемчужин архитектуры Азербайджана.

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Palace of the Shirvanshahs – Şirvanşahlar Sarayı – Дворец ширваншахов

https://vk.com/video434648441_456240287

Περισσότερα:

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs (Azerbaijani: Şirvanşahlar Sarayı, Persian: کاخ شروانشاهان) is a 15th-century palace built by the Shirvanshahs and described by UNESCO as “one of the pearls of Azerbaijan’s architecture”. It is located in the Inner City of Baku, Azerbaijan and, together with the Maiden Tower, forms an ensemble of historic monuments inscribed under the UNESCO World Heritage List of Historical Monuments. The complex contains the main building of the palace, Divanhane, the burial-vaults, the shah’s mosque with a minaret, Seyid Yahya Bakuvi’s mausoleum (the so-called “mausoleum of the dervish”), south of the palace, a portal in the east, Murad’s gate, a reservoir and the remnants of a bath house. Earlier, there was an ancient mosque, next to the mausoleum. There are still ruins of the bath and the lamb, belong to the west of the tomb.

In the past, the palace was surrounded by a wall with towers and, thus, served as the inner stronghold of the Baku fortress. Despite the fact that at the present time no traces of this wall have survived on the surface, as early as the 1920s, the remains of apparently the foundations of the tower and the part of the wall connected with it could be distinguished in the north-eastern side of the palace.

There are no inscriptions survived on the palace itself. Therefore, the time of its construction is determined by the dates in the inscriptions on the architectural monuments, which refer to the complex of the palace. Such two inscriptions were completely preserved only on the tomb and minaret of the Shah’s mosque. There is a name of the ruler who ordered to establish these buildings in both inscriptions is the – Shirvan Khalil I (years of rule 1417–1462). As time of construction – 839 (1435/36) was marked on the tomb, 845 (1441/42) on the minaret of the Shah’s mosque.

The burial vault, the palace and the mosque are built of the same material, the grating and masonry of the stone are the same.

The plan of the palace

The Palace

Divan-khana

Seyid Mausoleum Yahya Bakuvi

The place of the destroyed Kei-Kubad mosque

The Eastern portal

The Palace Mosque

The Shrine

Place of bath

Ovdan

Δείτε το βίντεο:

Το Ανάκτορο των Σάχηδων του Σιρβάν (Σιρβάν-σαχ), Μπακού – Αζερμπαϊτζάν

Περισσότερα:

Τα ανάκτορα των Σιρβανσάχ (αζερικά: Şirvanşahlar Sarayı) είναι ανάκτορο κατασκευασμένο στο Μπακού, Αζερμπαϊτζάν, τον 13ο έως 16ο αιώνα.

Το ανάκτορο κατασκευάστηκε από τη δυναστεία των Σιρβανσάχ κατά τη διάρκεια της βασιλείας του Χαλίλ-Ουλλάχ, όταν η πρωτεύουσα μετακινήθηκε από τη Σαμάχι στο Μπακού.

Το ανάκτορο αποτελεί αρχιτεκτονικά συγκρότημα με το περίπτερο Ντιβανχανά, το ιερό των Σιρβανσάχ, το τζαμί του παλατιού, χτισμένο το 1441, μαζί με το μιναρέ του, τα λουτρά και το μαυσωλείο.

Το 1964, το ανάκτορο ανακηρύχθηκε μουσείο-μνημείο και τέθηκε υπό κρατική προστασία.

Το 2000 ανακηρύχθηκε μνημείο παγκόσμιας κληρονομιάς από τη UNESCO μαζί με την παλιά πόλη του Μπακού και τον Παρθένο Πύργο.

Παρά το γεγονός ότι το συγκρότημα κατασκευάστηκε σε διαφορετικές χρονικές περιόδους, το συγκρότημα δίνει ομοιόμορφη εντύπωση, βασισμένη στην αρχιτεκτονικό σχολή του Σιρβάν-Αμπσερόν.

Με τη δημιουργία κυβικών και με πολλές προσόψεις αρχιτεκτονικών όγκων, οι τοίχοι είναι διακοσμημένοι με ανάγλυφα μοτίβα.

Κάθε αρχιτέκτονας, εξαιτίας των παραδόσεων και της αισθητικής που χρησιμοποιήθηκε από τους προκατόχους του, τον ανέπτυξε και τον εμπλούτισε δημιουργικά, με αποτέλεσμα τα επιμέρους κτίσματα να έχουν δημιουργούν την αίσθηση της ενότητας, ρυθμού και αναλογίας των βασικών αρχιτεκτονικών μορφών, δηλαδή του κυβικού όγκου των κτιρίων, των θόλων και των πυλών.

Με την κατάκτηση του Μπακού από τους Σαφαβίδες το 1501, το παλάτι λεηλατήθηκε.

Όλοι οι θησαυροί των Σιρβανσάχ, όπλα, πανοπλίες, κοσμήματα, χαλιά, μπροκάρ, σπάνια βιβλία από τη βιβλιοθήκης του παλατιού, πιάτα από ασήμι και χρυσό, μεταφέρθηκαν από τους Σαφαβίδες στη Ταμπρίζ.

Αλλά μετά την μάχη του Τσαλντιράν το 1514 μεταξύ του στρατού του σουλτάνου της Οθωμανικής Αυτοκρατορίας Σελίμ Α΄ και τους Σαφαβίδες, η οποία έληξε με ήττα των δεύτερων, οι Τούρκοι πήραν τον θησαυρό των Σιρβανσάχ ως λάφυρα.

Σήμερα βρίσκονται στις συλλογές μουσείων της Τουρκίας, του Ιράν, της Βρετανίας, της Γαλλίας, της Ρωσίας, της Ουγγαρίας.

Μερικά χαλιά του ανακτόρου φυλάσσονται στο μουσείο Βικτώριας και Αλβέρτου του Λονδίνου και τα αρχαία βιβλία φυλάσσονται σε αποθετήρια βιβλίων στην Τεχεράνη, το Βατικανό και την Αγία Πετρούπολη.

========================

Διαβάστε:

The Shirvanshah Palace

The Splendor of the Middle Ages

No tour of Baku’s Ichari Shahar (Inner City) would be complete without a stop at the 15th-century Shirvanshah complex. The Shirvanshahs ruled the state of Shirvan in northern Azerbaijan from the 6th to the 16th centuries. Their attention first shifted to Baku in the 12th century, when Shirvanshah Manuchehr III ordered that the city be surrounded with walls. In 1191, after a devastating earthquake destroyed the capital city of Shamakhi, the residence of the Shirvanshahs was moved to Baku, and the foundation of the Shirvanshah complex was laid. This complex, built on the highest point of Ichari Shahar, remains as one of the most striking monuments of medieval Azerbaijani architecture.

Το Ντιβάν-χανέ

Much of the construction was done in the 15th century, during the reign of Khalilullah I and his son Farrukh Yassar in 1435-1442.

An Egyptian historian named as-Suyuti described the father in superlative terms: “He was the most honored among rulers, the most pious, worthy and just. He was the last of the great Muslim rulers. He ruled the Shirvan and Shamakhi kingdoms for 50 years. He died in 1465, when he was about 100 years old, but he had good eyes and excellent health.”

The buildings that belong to the complex include what may have been living quarters, a mosque, the octagonal-shaped Divankhana (Royal Assembly), a tomb for royal family members, the mausoleum of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi (a famous astronomer of the time) and a bathhouse.

All of these buildings except for the living premises and bathhouse are fairly well preserved. The Shirvanshah complex itself is currently under reconstruction. It has 27 rooms on the first floor and 25 on the second.

Like so many other old buildings in Baku, the real function of the Shirvanshah complex is still under investigation. Though commonly described as a palace, some experts question this. The complex simply doesn’t have the royal grandeur and huge spaces normally associated with a palace; for instance, there are no grand entrances for receiving guests or huge royal bedrooms. Most of the rooms seem more suitable for small offices or monks’ living quarters.

Divankhana

This unique building, located on the upper level of the grounds, takes on the shape of an octagonal pavilion. The filigree portal entrance is elaborately worked in limestone.

The central inscription with the date of the Assembly’s construction and the name of the architect may have been removed after Shah Ismayil Khatai (famous king from Southern Azerbaijan) conquered Baku in 1501.

However, there are two very interesting hexagonal medallions on either side of the entrance. Each consists of six rhombuses with very unusual patterns carved in stone. Each elaborate design includes the fundamental tenets of the Shiite faith: “There is no other God but God. Mohammad is his prophet. Ali is the head of the believers.” In several rhombuses, the word “Allah” (God) is hewn in reverse so that it can be read in a mirror. It seems looking-glass reflection carvings were quite common in the Oriental world at that time.

Scholars believe that the Divankhana was a mausoleum meant for, or perhaps even used for, Khalilullah I. Its rotunda resembles those found in the mausoleums of Bayandur and Mama-Khatun in Turkey. Also, the small room that precedes the main octagonal hall is a common feature in mausoleums of Shirvan.

The Royal Tomb

This building is located in the lower level of the grounds and is known as the Turba (burial vault). An inscription dates the vault to 1435-1436 and says that Khalilullah I built it for his mother Bika khanim and his son Farrukh Yamin. His mother died in 1435 and his son died in 1442, at the age of seven. Ten more tombs were discovered later on; these may have belonged to other members of the Shah’s family, including two more sons who died during his own lifetime.

The entrance to the tomb is decorated with stalactite carvings in limestone. One of the most interesting features of this portal is the two drop-shaped medallions on either side of the Koranic inscription. At first, they seem to be only decorative.

The Turba is one of the few areas in the Shirvanshah complex where we actually know the name of the architect who built the structure. In the portal of the burial vault, the name “Me’mar (architect) Ali” is carved into the design, but in reverse, as if reflected in a mirror.

Some scholars suggest that if the Shah had discovered that his architect inscribed his own name in a higher position than the Shah’s, he would have been severely punished. The mirror effect was introduced so that he could leave his name for posterity.

Remnants of History

Another important section of the grounds is the mosque. According to complicated inscriptions on its minaret, Khalilullah I ordered its construction in 1441. This minaret is 22 meters in height (approximately 66 feet). Key Gubad Mosque, which is just a few meters outside the complex, was built in the 13th century. It was destroyed in 1918 in a fire; only the bases of its walls and columns remain. Nearby is the 15th-century Mausoleum, which is said to be the burial place of court astronomer Seyid Yahya Bakuvi.

Murad’s Gate was a later addition to the complex. An inscription on the gate tells that it was built by a Baku citizen named Baba Rajab during the rule of Turkish sultan Murad III in 1586. It apparently served as a gateway to a building, but it is not known what kind of building it was or even if it ever existed.

In the 19th century, the complex was used as an arms depot. Walls were added around its perimeter, with narrow slits hewn out of the rock so that weapons could be fired from them. These anachronistic details don’t bear much connection to the Shirvanshahs, but they do hint at how the buildings have managed to survive the political vicissitudes brought on by history.

Visitors to the Shirvanshah complex can also see some of the carved stones from the friezes that were brought up from the ruined Sabayil fortress that lies submerged underwater off Baku’s shore. The stones, which now rest in the courtyard, have carved writing that records the genealogy of the Shirvanshahs.

The complex was designated as a historical site in 1920, and reconstruction has continued off and on ever since that time. According to Sevda Dadashova, Director, restoration is currently progressing, though much slower than desired because of a lack of funding.

https://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/82_folder/82_articles/82_shirvanshah.html

========================

The Palace of the Shirvanshahs

by Kamil Ibrahimov

Baku’s Old City is a treasure trove of Azerbaijani history. Its stone buildings and mazy streets hold secrets that have still to be discovered. A masterpiece of Old City architecture, rich in history but with questions still unanswered, is the medieval residence of the rulers of Shirvan, the Shirvanshahs´ Palace.

The State of Shirvan

The state of Shirvan was formed in 861 and became the longest-surviving state in northern Azerbaijan. The first dynasty of the state of Shirvan was the Mazyadi dynasty (861-1027), founded by Mahammad ibn Yezid, an Arab vicegerent who lived in Shamakhi.

In the 10th century, the Shirvanshahs took Derbent, now in the Russian Federation. Under the Mazyadis, the state of the Shirvanshahs stretched from Derbent to the Kur River. The capital of this state was the town of Shamakhi.

In the first half of the 11th century, the Mazyadi dynasty was replaced by the Kasrani dynasty (1028-1382). The state of Shirvan flourished under the Shirvanshahs, Manuchehr III and his son Akhsitan. The last ruler in this dynasty was Hushang. His reign was unpopular and Hushang was killed in a rebellion.

The Kasrani dynasty was later replaced by the Derbendi dynasty (1382-1538), founded by Ibrahim I (1382-1417). Ibrahim I was a well-known but bankrupt feudal ruler from Shaki. His ancestors had been rulers in Derbent, hence the dynasty´s name. Ibrahim was a wise and peace-loving ruler and for some time managed to protect Shirvan from invasion.

To prevent the country´s destruction by Timur (Tamerlane), Ibrahim I took gifts to Timur´s headquarters and obtained internal independence for Shirvan. Ibrahim I failed to unite all Azerbaijani lands under his rule, but he did manage to make Shirvan a strong and independent state.

Baku becomes capital of Shirvan

The 15th century was a period of economic and cultural revival for Shirvan. Since this was a time of peace in Shirvan, major progress was made in the arts, architecture and trade. Shamakhi remained the capital of Shirvan at the start of the century, but an earthquake and constant attacks by the Kipchaks, a Turkic people, led the capital to be moved to Baku.

The city of Baku was the capital of the country during the rule of the Shirvanshahs Khalilullah I (1417-62) and his son Farrukh Yasar (1462-1500).

While tension continued in Shamakhi, Baku developed in a relatively quiet environment. It is known that strong fortress walls were built in Baku as early as the 12th century. After the capital was moved to Baku, the Palace of the Shirvanshahs was erected at the highest point of the city, in what had been one of the most densely populated areas. The palace complex consists of nine buildings – the palace itself, the Courtroom, the Dervish´s Tomb, the Eastern Gate, the Shah Mosque, the Keygubad Mosque, the palace tomb, the bathhouse and the reservoir.

The buildings of the complex are located in three courtyards that are on different levels, 5.6 metres above one another. Since the palace is built on uneven ground, it does not have an orderly architectural plan. The entire complex is constructed from limestone. Of all the buildings, the palace itself has suffered the most wear and tear over the years. The palace was looted in 1500 after Farrukh Yasar was killed in fighting between the Shirvanshahs and the Safavids. As the Iranian and Ottoman empires vied for power in the South Caucasus, the state of Shirvan, on the crossing-point of various caravan routes, suffered frequent attacks. Consequently, the palace was badly damaged many times. Proof of this is the Murad Gate which was built during Ottoman rule.

What is now Azerbaijan was occupied by Russia on 10 February 1828. The Shirvanshahs´ Palace became the Russian military headquarters and many palace buildings were destroyed. In 1954, the Complex of the Palace of the Shirvanshahs was made a State Historic-Architectural Reserve and Museum. In 1960, the authorities of the Soviet republic decided to promote the palace as an architectural monument.

The Palace Building

The palace is a two-storey building in an irregular, rectangular shape. In order to provide better illumination of the palace, the south-eastern part of the building was constructed on different levels. Initially there were 52 rooms in the palace, of which 27 were on the ground floor and 25 on the first floor. The shah and his family lived on the upper floor, while servants and others lived on the lower floor.

The Tomb Built by Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar (also known as the Courtroom or Divankhana)

Shirvanshah Farrukh Yasar had the tomb constructed in the upper courtyard of the palace complex. Its north side and one of its corners adjoin the residential building. The tomb consists of an octagonal rotunda, completed with a dodecagonal dome. Its octagonal hall is surrounded by an open balcony or portico. The balcony is edged with nine columns which still have their original capitals. The rotunda stands in a small courtyard which also has an open balcony running around its edge. The balcony´s columns and arches are the same shape as those of the rotunda. The outer side of the columns has a stone with the image of a dove, the symbol of freedom, and two stone chutes to drain water away. Some researchers believe that this building was used for official receptions and trials and call it the Courtroom. The architectural work in the tomb was not completed. The tomb is considered one of the finest examples of medieval architecture, not only in Azerbaijan but in the whole Middle East.

The Dervish´s Tomb

The Dervish´s Tomb is located in the southern part of the middle courtyard. Some historians maintain that it is the tomb of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi, who was a royal scholar and astronomer under Khalilullah I.

Other historians say that all the buildings in the lower courtyard of the palace, including the Dervish´s Tomb, are part of a complex where dervishes lived, but there is little evidence for this.

The Keygubad Mosque

Now in ruins, the Keygubad Mosque was a mosque-cum-madrasah joined to the Dervish´s Tomb.

The tomb was located in the southern part of the mosque.

The mosque consisted of a rectangular prayer hall and a small corridor in front of it. In the centre of the hall four columns supported the dome.

Historian Abbasgulu Bakikhanov wrote that Bakuvi taught and prayed in the mosque: “The cell where he prayed, the school where he worked and his grave are there, in the mosque”.

Keygubad Shirvanshah ruled from 1317 to 1343 and was Sheikh Ibrahim´s grandfather.

The Eastern Gate

The Eastern or Murad Gate is the only part of the complex that dates to the 16th century. Two medallions on the upper frame of the Murad Gate bear the inscription: “This building was constructed under the great and just Sultan Murad III on the basis of an order by Racab Bakuvi in 994” (1585-86).

The Tomb of the Shirvanshahs

There are two buildings in the lower courtyard – the tomb and the Shah Mosque. A round wall encloses the lower courtyard, separating it from the other yards. When you look at the tomb from above, you can see that it is rectangular in shape, decorated with an engraved star and completed with an octagonal dome. While the tomb was being built, blue glazed tiles were placed in the star-shaped mortises on the dome.

An inscription at the entrance says: “Protector of the religion, man of the prophet, the great Sultan Shirvanshah Khalilullah, may God make his reign as shah permanent, ordered the building of this light tomb for his mother and seven-year-old son (may they rest in peace) 839” (1435-36). The architect´s name is also inscribed between the words “God” and “Mohammad” on another decorative inscription on the portal which can be read only using a mirror. The inscription says “God, architect Ali, Mohammad”.

A skeleton 2.1 metres tall was found opposite the entrance to the tomb. This is believed to be Khalilullah I´s own grave. A comb, a gold earring and other items of archaeological interest were found there.

The Shah Mosque

The Shah Mosque is in the lower courtyard, alongside the mausoleum. The mosque is 22 metres high. An inscription around the minaret says: “The Great Sultan Khalilullah I ordered the erection of this minaret. May God prolong his rule as Shah. Year 845” (1441-42).

Stairs lead from a hollow in the wall behind the minbar or pulpit to another small room. Stone traceries on the windows decorate the mosque.

The Palace Bathhouse

The palace bathhouse is located in the lowest courtyard of the complex. Like all bathhouses in the Old City, this one was built underground to ensure that the temperature inside was kept stable. As time passed the level of the earth rose and covered it completely. The bathhouse was found by chance in 1939. In 1953 part of it was cleaned and in 1961 restoration work was done and the dome repaired. The walls in one of the side rooms are covered with glazed tiles and this room is thought to have been the shah´s room.

Cistern

The cistern, part of an underground water distribution system, was constructed in the lower part of the bathhouse to supply the Shirvanshahs´ Palace with water. Water came into the cistern via ceramic pipes which were part of the Shah´s Water Pipeline, laid from a high part of the city. The cistern is located underground and its entrance has the shape of a portal. Numerous stairs lead from the entrance down to the storage facility. A link between the cistern and the bathhouse can be seen from the side lobby. The cistern was found by chance during restoration work in 1954.

Literature

S.B. Ashurbayli: Государство Ширваншахов (The State of the Shirvanshahs), Baku, Elm, 1983; and Bakı şəhərinin tarixi (The History of the City of Baku), Baku, Azarnashr, 1998

F.A. Ibrahimov and K.F. Ibrahimov: Bakı İçərişəhər (Baku Inner City), Baku, OKA, Ofset, 2002. Kamil Farhadoghlu: Bakı İçərişəhər (Baku Inner City), Sh-Q, 2006; and Baku´s Secrets are Revealed (Bakının sirləri açılır), Baku, 2008

E.A. Pakhomov: Отчет о работах по шахскому дворцу в Баку (Report on Work in the Shah´s Palace in Baku), News of the AAK, Issue II, Baku, 1926; and Первоначальная очистка шахского дворца в Баку (Initial Clearing of the Shah´s Palace in Baku), News of the AAK, Issue II, Baku, 1926

Chingiz Gajar: Старый Баку (Old Baku), OKA, Ofset, 2007

M. Huseynov, L. Bretanitsky, A. Salamzadeh, История архитектуры Азербайджана (History of the Architecture of Azerbaijan). Moscow, 1963

M.S. Neymat, Корпус эпиграфических памятников Азербайджана (Azerbaijan´s Epigraphic Monuments), Baku, Elm, 1991

A.A. Alasgarzadah, Надписи архитектурных памятников Азербайджана эпохи Низами (Inscriptions on the architectural monuments of Azerbaijan from the era of Nizami) in the collection, Архитектура Азербайджана эпохи Низами (Azerbaijan in the Era of Nizami), Moscow, 1947.

http://www.visions.az/en/news/159/cdc770e3/

=============================

Šervānšāhs

Šervānšāhs (Šarvānšāhs), the various lines of rulers, originally Arab in ethnos but speedily Persianized within their culturally Persian environment, who ruled in the eastern Caucasian region of Šervān from mid-ʿAbbasid times until the age of the Safavids.

The title itself probably dates back to pre-Islamic times, since Ebn Ḵordāḏbeh, (pp. 17-18) mentions the Shah as one of the local rulers given his title by the Sasanid founder Ardašir I, son of Pāpak. Balāḏori (Fotuḥ, pp. 196, 203-04) records that the first Arab raiders into the eastern Caucasus in ʿOṯmān’s caliphate encountered, amongst local potentates, the shahs of Šarvān and Layzān, these rulers submitting at this time to the commander Salmān b. Rabiʿa Bāheli.

The caliph Manṣur’s governor of Azerbaijan and northwestern Persia, Yazid b. Osayd Solami, took possession of the naphtha wells (naffāṭa) and salt pans (mallāḥāt) of eastern Šervān; the naphtha workings must mark the beginnings of what has become in modern times the vast Baku oilfield.

By the end of this 8th century, Šervān came within the extensive governorship, comprising Azerbaijan, Arrān, Armenia and the eastern Caucasus, granted by Hārun-al-Rašid in 183/799 to the Arab commander Yazid b. Mazyad, and this marks the beginning of the line of Yazidi Šervānšāhs which was to endure until Timurid times and the end of the 14th century (see Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-42 n. 67).

Most of what we know about the earlier centuries of their power derives from a lost Arabic Taʾriḵ Bāb al-abwāb preserved within an Arabic general history, the Jāmeʿ al-dowal, written by the 17th century Ottoman historian Monajjem-bāši, who states that the history went up to c. 500/1106 (Minorsky 1958, p. 41). It was exhaustively studied, translated and explained by V. Minorsky (Minorsky, 1958; Ḥodud al-ʿālam, commentary pp. 403-11); without this, the history of this peripheral part of the mediaeval Islamic world would be even darker than it is.

The history of Šervānšāhs was clearly closely bound up with that of another Arab military family, the Hāšemis of Bāb al-abwāb/Darband (see on them Bosworth, 1996, pp. 143-44 n. 68), with the Šervānšāhs at times ruling in the latter town (at times invited into Darband by rebellious elements there, see Minorsky 1958, pp. 27, 29-30), and there was frequent intermarriage between the two families.

By the later 10th century, the Shahs had expanded from their capital of Šammāḵiya/Yazidiya to north of the Kura valley and had absorbed the petty principalities of Layzān and Ḵorsān, taking over the titles of their rulers (see Ḥodud al-ʿālam, tr. Minorsky, pp. 144-45, comm. pp. 403-11), and from the time of Yazid b. Aḥmad (r. 381-418/991-1028) we have a fairly complete set of coins issued by the Shahs (see Kouymjian, pp. 136-242; Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41).

Just as an originally Arab family like the Rawwādids in Azerbaijan became Kurdicized from their Kurdish milieu, so the Šervānšāhs clearly became gradually Persianized, probably helped by intermarriage with the local families of eastern Transcaucasia; from the time of Manučehr b. Yazid (r. 418-25/1028-34), their names became almost entirely Persian rather than Arabic, with favored names from the heroic national Iranian past and with claims made to descent from such figures as Bahrām Gur (see Bosworth, 1996, pp. 140-41).

The anonymous local history details frequent warfare of the Shahs with the infidel peoples of the central Caucasus, such as the Alans, and the people of Sarir (i.e. Daghestan), and with the Christian Georgians and Abḵāz to their west. In 421/1030 Rus from the Caspian landed near Baku, defeated in battle the Shah Manučehr b. Yazid and penetrated into Arrān, sacking Baylaqān before departing for Rum, i.e. the Byzantine lands (Minorsky, 1958, pp. 31-32). Soon afterwards, eastern Transcaucasia became exposed to raids through northern Persia of the Turkish Oghuz. Already in c. 437/1045, the Shah Qobāḏ b. Yazid had to built a strong stone wall, with iron gates, round his capital Yazidiya for fear of the Oghuz (Minorsky 1958, p. 33). In 458-59/1066-67 the Turkish commander Qarategin twice invaded Šervān, attacking Yazidiya and Baku and devastating the countryside.

Then after his Georgian campaign of 460/1058 Alp Arslan himself was in nearby Arrān, and the Shah Fariborz b. Sallār had to submit to the Saljuq sultan and pay a large annual tribute of 70,000 dinars, eventually reduced to 40,000 dinars; coins issued soon after this by Fariborz acknowledge the ʿAbbasid caliph and then Sultan Malekšāh as his suzerain (Minorsky 1958, pp. 35-38, 68; Kouymjian, pp. 146ff, who surmises that, since we have no evidence for the minting of gold coins in Azerbaijan and the Caucasus at this time, Fariborz must have paid the tribute in Byzantine or Saljuq coins).

Fariborz’s diplomatic and military skills thus preserved much of his family’s power, but after his death in c. 487/1094 there seem to have been succession disputes and uncertainty (the information of the Taʾriḵ Bāb al-abwāb dries up after Fariborz’s death).

In the time of the Saljuq sultan Maḥmud b. Moḥammad (r. 511-25/1118-31), Šervān was again occupied by Saljuq troops, and the disturbed situation there encouraged invasions of Šammāḵa and Darband by the Georgians. During the middle years of the 12th century, Šervān was virtually a protectorate of Christian Georgia. There were marriage alliances between the Shahs and the Bagratid monarchs, who at times even assumed the title of Šervānšāh for themselves; and the regions of Šakki, Qabala and Muqān came for a time directly under Georgian rule (Nasawi, text, pp. 146, 174). The energies of the Yazidi Shahs had to be directed eastwards towards the Caspian, and on various occasions they expanded as far as Darband.