The Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis

At this time in 1962, the U.S. was in the thick of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Here’s a brief recap of what exactly happened during those thirteen days.

It’s not hard to imagine a world where at any given moment, you and everyone you know could be wiped out without warning at the push of a button. This was the reality for millions of people during the 45-year period after World War II, now known as the Cold War. As the United States and Soviet Union faced off across the globe, each knew that the other had nuclear weapons capable of destroying it. And destruction never loomed closer than during the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In 1961, the U.S. unsuccessfully tried to overthrow Cuba’s new communist government. That failed attempt was known as the Bay of Pigs, and it convinced Cuba to seek help from the U.S.S.R. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev was happy to comply by secretly deploying nuclear missiles to Cuba, not only to protect the island, but to counteract the threat from U.S. missiles in Italy and Turkey. By the time U.S. intelligence discovered the plan, the materials to create the missiles were already in place.

At an emergency meeting on October 16, 1962, military advisors urged an airstrike on missile sites and invasion of the island. But President John F. Kennedy chose a more careful approach. On October 22, he announced that the the U.S. Navy would intercept all shipments to Cuba, but a naval blockade was considered an act of war. Although the President called it a quarantine that did not block basic necessities, the Soviets didn’t appreciate the distinction.

Thus ensued the most intense six days of the Cold War. As the weapons continued to be armed, the U.S. prepared for a possible invasion. For the first time in history, the U.S. Military set itself to DEFCON 2, the defense readiness one step away from nuclear war. With hundreds of nuclear missiles ready to launch, the metaphorical Doomsday Clock stood at one minute to midnight.

But diplomacy carried on. In Washington, D.C., Attorney General Robert Kennedy secretly met with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. After intense negotiation, they reached the following proposal. The U.S. would remove their missiles from Turkey and Italy and promise to never invade Cuba in exchange for the Soviet withdrawal from Cuba under U.N. inspection. The crisis was now over.

While criticized at the time by their respective governments for bargaining with the enemy, contemporary historical analysis shows great admiration for Kennedy’s and Khrushchev’s ability to diplomatically solve the crisis. Overall, the Cuban Missile Crisis revealed just how fragile human politics are compared to the terrifying power they can unleash.

For a deeper dive into the circumstances of the Cuban Missile Crisis, be sure to watch The history of the Cuban Missile Crisis - Matthew A. Jordan

Animation by Patrick Smith

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

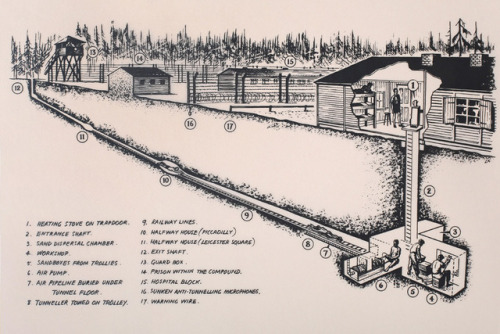

March 24th 1944: The ‘Great Escape’

On this day in 1944, a group of Allied prisoners of war staged a daring escape attempt from the German prisoner of war camp at Stalag Luft III. This camp, located in what is now Poland, held captured Allied pilots mostly from Britain and the United States. In 1943, an Escape Committee under the leadership of Squadron Leader Roger Bushell of the RAF, supervised prisoners surreptitiously digging three 30 foot tunnels out of the camp, which they nicknamed ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’ and ‘Harry’. The tunnels led to woods beyond the camp and were remarkably sophisticated - lined with wood, and equipped with rudimentary ventilation and electric lighting. The successful construction of the tunnels was particularly impressive as the Stalag Luft III camp was designed to make it extremely difficult to tunnel out as the barracks were raised and the area had a sandy subsoil. ‘Tom’ was discovered by the Germans in September 1943, and ‘Dick’ was abandoned to be used as a dirt depository, leaving ‘Harry’ as the prisoners’ only hope. By the time of the escape, American prisoners who had assisted in tunneling had been relocated to a different compound, making the escapeees mostly British and Commonwealth citizens. 200 airmen had planned to make their escape through the ‘Harry’ tunnel, but on the night of March 24th 1944, only 76 managed to escape the camp before they were discovered by the guards. However, only three of the escapees - Norwegians Per Bergsland and Jens Müller and Dutchman Bram van der Stok - found their freedom. The remaining 73 were recaptured, and 50 of them, including Bushell, were executed by the Gestapo on Adolf Hitler’s orders, while the rest were sent to other camps. While the escape was generally a failure, it helped boost morale among prisoners of war, and has become enshrined in popular memory due to its fictionalised depiction in the 1963 film The Great Escape.

“Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug – Tom, Dick, and Harry. One will succeed!” - Roger Bushell

Why do we love?

Ah, romantic love; beautiful and intoxicating, heart-breaking and soul-crushing… often all at the same time! Why do we choose to put ourselves though its emotional wringer? Does love make our lives meaningful, or is it an escape from our loneliness and suffering? Is love a disguise for our sexual desire, or a trick of biology to make us procreate? Is it all we need? Do we need it at all?

If romantic love has a purpose, neither science nor psychology has discovered it yet – but over the course of history, some of our most respected philosophers have put forward some intriguing theories.

1. Love makes us whole, again / Plato (427—347 BCE)

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato explored the idea that we love in order to become complete. In his Symposium, he wrote about a dinner party at which Aristophanes, a comic playwright, regales the guests with the following story. Humans were once creatures with four arms, four legs, and two faces. One day they angered the gods, and Zeus sliced them all in two. Since then, every person has been missing half of him or herself. Love is the longing to find a soul mate who will make us feel whole again… or at least that’s what Plato believed a drunken comedian would say at a party.

2. Love tricks us into having babies / Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Much, much later, German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer maintained that love, based in sexual desire, was a “voluptuous illusion”. He suggested that we love because our desires lead us to believe that another person will make us happy, but we are sorely mistaken. Nature is tricking us into procreating and the loving fusion we seek is consummated in our children. When our sexual desires are satisfied, we are thrown back into our tormented existences, and we succeed only in maintaining the species and perpetuating the cycle of human drudgery. Sounds like somebody needs a hug.

3. Love is escape from our loneliness / Russell (1872-1970)

According to the Nobel Prize-winning British philosopher Bertrand Russell we love in order to quench our physical and psychological desires. Humans are designed to procreate; but, without the ecstasy of passionate love, sex is unsatisfying. Our fear of the cold, cruel world tempts us to build hard shells to protect and isolate ourselves. Love’s delight, intimacy, and warmth helps us overcome our fear of the world, escape our lonely shells, and engage more abundantly in life. Love enriches our whole being, making it the best thing in life.

4. Love is a misleading affliction / Buddha (~6th- 4thC BCE)

Siddhartha Gautama. who became known as ‘the Buddha’, or ‘the enlightened one’, probably would have had some interesting arguments with Russell. Buddha proposed that we love because we are trying to satisfy our base desires. Yet, our passionate cravings are defects, and attachments – even romantic love – are a great source of suffering. Luckily, Buddha discovered the eight-fold path, a sort of program for extinguishing the fires of desire so that we can reach ‘nirvana’ – an enlightened state of peace, clarity, wisdom, and compassion.

5. Love lets us reach beyond ourselves / Beauvoir (1908-86)

Let’s end on a slightly more positive note. The French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir proposed that love is the desire to integrate with another and that it infuses our lives with meaning. However, she was less concerned with why we love and more interested in how we can love better. She saw that the problem with traditional romantic love is it can be so captivating that we are tempted to make it our only reason for being. Yet, dependence on another to justify our existence easily leads to boredom and power games.

To avoid this trap, Beauvoir advised loving authentically, which is more like a great friendship: lovers support each other in discovering themselves, reaching beyond themselves, and enriching their lives and the world, together.

Though we might never know why we fall in love, we can be certain that it’ll be an emotional rollercoaster ride. It’s scary and exhilarating. It makes us suffer and makes us soar. Maybe we lose ourselves. Maybe we find ourselves. It might be heartbreaking or it might just be the best thing in life. Will you dare to find out?

From the TED-Ed Lesson Why do we love? A philosophical inquiry - Skye C. Cleary

Animation by Avi Ofer

My boyfriend, @inlove-with-a-spine, is very uninformed about Southeast Asian fruits (he only knows durian) which inspired me to find these online.

I’m pretty sure the names are different in other Southeast Asian countries, though.

From left to right (in Indonesian):

Duku

Jambu monyet

Jeruk

Lengkeng

Kedondong

Manggis

Rambutan

Nangka

Salak

Sawo

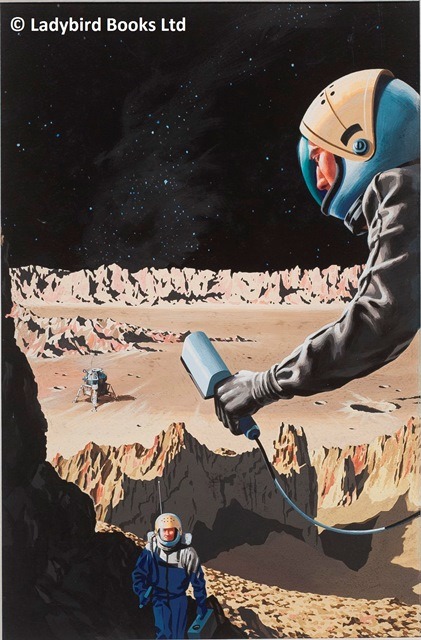

The @unirdg-collections Squint

The University of Reading holds the archive of original artwork for the much-loved Ladybird children’s book. This painting on board was used to illustrate Exploring Space, a Ladybird ‘Achievements’ Book first published in 1964. The artwork was created by Brian Knight.

If you look closely at the painting, you can see the faint trace of Knight’s initial design for the lunar landing module - just visible under the later amendment.

Published before the first Moon landing in 1969, the fantasy spacecraft was sleek and utopian. It typifies the extent to which The Space Race captured our mid-century imaginations and permeated visual culture. The later correction, based on the Eagle Lunar Module, was printed in subsequent revisions to the book. It was an acknowledgment of a successful mission and testament to Ladybird’s emphasis on accuracy for its young readers.

All artwork is © Ladybird Books Ltd.

Aphasia: The disorder that makes you lose your words

It’s hard to imagine being unable to turn thoughts into words. But, if the delicate web of language networks in your brain became disrupted by stroke, illness or trauma, you could find yourself truly at a loss for words. This disorder, called “aphasia,” can impair all aspects of communication. Approximately 1 million people in the U.S. alone suffer from aphasia, with an estimated 80,000 new cases per year. About one-third of stroke survivors suffer from aphasia, making it more prevalent than Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis, yet less widely known.

There are several types of aphasia, grouped into two categories: fluent (or “receptive”) aphasia and non-fluent (or “expressive”) aphasia.

People with fluent aphasia may have normal vocal inflection, but use words that lack meaning. They have difficulty comprehending the speech of others and are frequently unable to recognize their own speech errors.

People with non-fluent aphasia, on the other hand, may have good comprehension, but will experience long hesitations between words and make grammatical errors. We all have that “tip-of-the-tongue” feeling from time to time when we can’t think of a word. But having aphasia can make it hard to name simple everyday objects. Even reading and writing can be difficult and frustrating.

It’s important to remember that aphasia does not signify a loss in intelligence. People who have aphasia know what they want to say, but can’t always get their words to come out correctly. They may unintentionally use substitutions, called “paraphasias” – switching related words, like saying dog for cat, or words that sound similar, such as house for horse. Sometimes their words may even be unrecognizable.

So, how does this language-loss happen? The human brain has two hemispheres. In most people, the left hemisphere governs language. We know this because in 1861, the physician Paul Broca studied a patient who lost the ability to use all but a single word: “tan.” During a postmortem study of that patient’s brain, Broca discovered a large lesion in the left hemisphere, now known as “Broca’s area.” Scientists today believe that Broca’s area is responsible in part for naming objects and coordinating the muscles involved in speech. Behind Broca’s area is Wernicke’s area, near the auditory cortex. That’s where the brain attaches meaning to speech sounds. Damage to Wernicke’s area impairs the brain’s ability to comprehend language. Aphasia is caused by injury to one or both of these specialized language areas.

Fortunately, there are other areas of the brain which support these language centers and can assist with communication. Even brain areas that control movement are connected to language. Our other hemisphere contributes to language too, enhancing the rhythm and intonation of our speech. These non-language areas sometimes assist people with aphasia when communication is difficult.

However, when aphasia is acquired from a stroke or brain trauma, language improvement may be achieved through speech therapy. Our brain’s ability to repair itself, known as “brain plasticity,” permits areas surrounding a brain lesion to take over some functions during the recovery process. Scientists have been conducting experiments using new forms of technology, which they believe may encourage brain plasticity in people with aphasia.

Meanwhile, many people with aphasia remain isolated, afraid that others won’t understand them or give them extra time to speak. By offering them the time and flexibility to communicate in whatever way they can, you can help open the door to language again, moving beyond the limitations of aphasia.

Don’t play, play - Singlish is studied around the globe

Blogger Wendy Cheng’s Web video series Xiaxue’s Guide To Life and Jack Neo’s Ah Boys To Men film franchise are well-known shows among Singaporeans. For one thing, they are filled with colloquial terms, local references and copious doses of Singlish terms such as “lah” and “lor”.

But they are not merely for entertainment. In recent years, such shows have found a place in universities around the world, where linguists draw on dialogues used in these local productions to introduce to undergraduates and postgraduate students how Singlish has become a unique variety of the English language.

This comes even as concerns have been raised over how Singlish could impede the use of standard English here.

From Italy and Germany to Japan, at least seven universities around the world have used Singlish as a case study in linguistics courses over the past decade. This is on top of more than 40 academics outside of Singapore - some of whom were previously based here - who have written books or papers on Singlish as part of their research.

How many did you know? All worth reading more about!!

11 New Facts Science Has Revealed About The Body

1. Hundreds of genes spring to life after you die - and they keep functioning for up to four days.

2. Livers grow by almost half during waking hours.

3. The root cause of eczema has finally been identified.

4. We were wrong - the testes are connected to the immune system after all.

5. The causes of hair loss and greying are linked, and for the first time, scientists have identified the cells responsible.

6. A brand new human organ has been classified - the mesentery - an organ that’s been hiding in plain sight in our digestive system this whole time.

7. An unexpected new lung function has been found - they also play a key role in blood production, with the ability to produce more than 10 million platelets (tiny blood cells) per hour.

8. Your appendix might actually be serving an important biological function- and one that our species isn’t ready to give up just yet.

9. The brain literally starts eating itself when it doesn’t get enough sleep. brain to clear a huge amount of neurons and synaptic connections away.

10. Neuroscientists have discovered a whole new role for the brain’s cerebellum - it could actually play a key role in shaping human behaviour.

11. Our gut bacteria are messing with us in ways we could never have imagined. Neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s might actually start out in the gut, rather than the brain, and there’s mounting evidence that the human microbiome could be to blame for chronic fatigue syndrome.

Quick Study of the Maiko’s Furisode Kimono+Undergarments!

Just a simple little vocabulary dump! Still learning the details (there are many!) and would love any corrections or elaborations to be made!

Hadajuban: The first layer underneath a Maiko’s kimono. It is said that Geiko and Maiko don’t wear underwear because it throws off the line of the kimono; instead, they wear multi-layer undergarments.

Nagajuban: Another garment with sleeves, made of cotton, that goes over the Hadajuban.

Koshihimo: An under-wrap belt that holds the undergarments together in a foundation shape for the kimono over it.

Korin belt: Ties the juban collars together.

Obi-Ita: Stiff padding that will help to hold the obi belt in place.

Obi-Makura: “Pillow” that ties around from the front. This supports the front of the obi belt. I’ve read it’s something only girls wearing kimono use.

Eri Shin: Long strand of cardboard or plastic that serves as a collar stiffener.

Tabi: White, sometimes buttoned up, socks that separate the big toe from the rest of the four toes. Worn along with a Maiko’s Okobo or Zori.

Furisode Kimono: Formal-looking kimono with a characteristic of long, billowy sleeves with the seam connecting the top sleeve to the hanging sleeve visible. This kimono is also a popular formal traditional kimono for unmarried women. Originally, furisode kimono were only worn by children (both boys and girls) from well-off or even wealthy families. This connects the tradition of the Maiko symbolizing “childhood” and “youthfulness”.

Maru Obi: Primarily used by Maiko (or traditional brides), these especially formal obi belts are heavy, rich with brocade embroidery and very long. Both sides are usually fully patterned; a Maiko wears her obi tied in the back, one end of the belt folded slightly over the other, cascading in a loose-look down to her ankles.

Obi-jime: A thin braid of stippled silk that wraps around the front of the obi and holds it together with a final touch. The obi clasps are expensive and beautiful bejeweled and are attached to the obi-jime to adorn the front of the kimono.

Please message me if you’d like to add an ingredient to this list! I work with google and the books I have for accurate and complete information, and sometimes I just can’t find all that I’m lookin’ for! Thanks!

( @gion-lady )

-

typing294 liked this · 1 year ago

typing294 liked this · 1 year ago -

xining20 liked this · 2 years ago

xining20 liked this · 2 years ago -

vemoon liked this · 4 years ago

vemoon liked this · 4 years ago -

shimmeringwind liked this · 4 years ago

shimmeringwind liked this · 4 years ago -

itsswizardry liked this · 4 years ago

itsswizardry liked this · 4 years ago -

crazyplantgirl liked this · 4 years ago

crazyplantgirl liked this · 4 years ago -

847vampire777 liked this · 4 years ago

847vampire777 liked this · 4 years ago -

finding-euphoria-xo liked this · 4 years ago

finding-euphoria-xo liked this · 4 years ago -

mellycoco liked this · 5 years ago

mellycoco liked this · 5 years ago -

watermelonflavoredvoid reblogged this · 5 years ago

watermelonflavoredvoid reblogged this · 5 years ago -

xxriverspirit liked this · 5 years ago

xxriverspirit liked this · 5 years ago -

eruthiawenluin liked this · 5 years ago

eruthiawenluin liked this · 5 years ago -

eirspeace reblogged this · 5 years ago

eirspeace reblogged this · 5 years ago -

oh-honeyhunny liked this · 5 years ago

oh-honeyhunny liked this · 5 years ago -

notyouraveragetroll liked this · 6 years ago

notyouraveragetroll liked this · 6 years ago -

milohohohohooho-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago

milohohohohooho-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago -

godsfavoriteasian liked this · 6 years ago

godsfavoriteasian liked this · 6 years ago -

crossedheartsnwalks liked this · 6 years ago

crossedheartsnwalks liked this · 6 years ago -

sweetie206 liked this · 6 years ago

sweetie206 liked this · 6 years ago -

gemnore liked this · 6 years ago

gemnore liked this · 6 years ago -

samsam0706 liked this · 6 years ago

samsam0706 liked this · 6 years ago -

cygnusstiers liked this · 6 years ago

cygnusstiers liked this · 6 years ago -

earthtoflora liked this · 6 years ago

earthtoflora liked this · 6 years ago -

gothamcitypoprocks liked this · 6 years ago

gothamcitypoprocks liked this · 6 years ago -

outre-viridity liked this · 6 years ago

outre-viridity liked this · 6 years ago -

tumbleweed-chaser liked this · 6 years ago

tumbleweed-chaser liked this · 6 years ago -

gcodegfb liked this · 6 years ago

gcodegfb liked this · 6 years ago -

cringecandy liked this · 6 years ago

cringecandy liked this · 6 years ago -

captainbingpot liked this · 6 years ago

captainbingpot liked this · 6 years ago -

primaryaccofhf liked this · 6 years ago

primaryaccofhf liked this · 6 years ago -

joyinexpression reblogged this · 6 years ago

joyinexpression reblogged this · 6 years ago -

joyinexpression liked this · 6 years ago

joyinexpression liked this · 6 years ago -

nicolastascong reblogged this · 6 years ago

nicolastascong reblogged this · 6 years ago -

nicolastascong liked this · 6 years ago

nicolastascong liked this · 6 years ago -

tpk1019 liked this · 6 years ago

tpk1019 liked this · 6 years ago -

ruffie19-blog liked this · 6 years ago

ruffie19-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

negativenopenada liked this · 6 years ago

negativenopenada liked this · 6 years ago -

darklord-8 reblogged this · 6 years ago

darklord-8 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

anaeovili reblogged this · 6 years ago

anaeovili reblogged this · 6 years ago -

jujupenguins reblogged this · 6 years ago

jujupenguins reblogged this · 6 years ago -

medvetalp liked this · 6 years ago

medvetalp liked this · 6 years ago -

snowfallpeacetext reblogged this · 6 years ago

snowfallpeacetext reblogged this · 6 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts