What Is The Smallest Possible Distance In The Universe?

What Is The Smallest Possible Distance In The Universe?

“At present, there is no way to predict what’s going to happen on distance scales that are smaller than about 10-35 meters, nor on timescales that are smaller than about 10-43 seconds. These values are set by the fundamental constants that govern our Universe. In the context of General Relativity and quantum physics, we can go no farther than these limits without getting nonsense out of our equations in return for our troubles.

It may yet be the case that a quantum theory of gravity will reveal properties of our Universe beyond these limits, or that some fundamental paradigm shifts concerning the nature of space and time could show us a new path forward. If we base our calculations on what we know today, however, there’s no way to go below the Planck scale in terms of distance or time. There may be a revolution coming on this front, but the signposts have yet to show us where it will occur.”

If you went down to smaller and smaller distance scales, you might imagine that you’ll start to see the Universe more clearly and in higher resolution. You’ll be able to hone in on the fundamental properties of nature, and glean more information the deeper you go. This is true, but only up to a point. Beyond that, you start running into the inescapable quantum rules that govern the Universe, and that means there’s a fundamental scale at which our best laws of physics cannot be trusted any longer.

That scale is the Planck scale, and for distances, it corresponds to about 10^-35 meters. It really is a problem for physics, and it’s high time you understood why.

More Posts from Ocrim1967 and Others

What is an Exoplanet?

An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside our solar system that orbits a star. The first evidence of an exoplanet was noted as early as 1917, but was not recognized as such. However, the first scientific detection of an exoplanet was in 1988. Shortly afterwards, the first confirmed detection was in 1992. As of 1 April 2018, there are 3,758 confirmed planets in 2,808 systems, with 627 systems having more than one planet.

The High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS, since 2004) has discovered about a hundred exoplanets while the Kepler space telescope (since 2009) has found more than two thousand. Kepler has also detected a few thousand candidate planets, of which about 11% may be false positives.

In several cases, multiple planets have been observed around a star. About 1 in 5 Sun-like stars have an “Earth-sized” planet in the habitable zone. Assuming there are 200 billion stars in the Milky Way, one can hypothesize that there are 11 billion potentially habitable Earth-sized planets in the Milky Way, rising to 40 billion if planets orbiting the numerous red dwarfs are included.

The least massive planet known is Draugr (also known as PSR B1257+12 A or PSR B1257+12 b), which is about twice the mass of the Moon. The most massive planet listed on the NASA Exoplanet Archive is HR 2562 b, about 30 times the mass of Jupiter, although according to some definitions of a planet, it is too massive to be a planet and may be a brown dwarf instead.

There are planets that are so near to their star that they take only a few hours to orbit and there are others so far away that they take thousands of years to orbit.

Some are so far out that it is difficult to tell whether they are gravitationally bound to the star. Almost all of the planets detected so far are within the Milky Way. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that extragalactic planets, exoplanets further away in galaxies beyond the local Milky Way galaxy, may exist. The nearest exoplanet is Proxima Centauri b, located 4.2 light-years (1.3 parsecs) from Earth and orbiting Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun.

Besides exoplanets, there are also rogue planets, which do not orbit any star and which tend to be considered separately, especially if they are gas giants, in which case they are often counted, like WISE 0855−0714, as sub-brown dwarfs. The rogue planets in the Milky Way possibly number in the billions (or more).

Some planets orbit one member of a binary star system, and several circumbinary planets have been discovered which orbit around both members of binary star. A few planets in triple star systems are known and one in the quadruple system Kepler-64.

Methods of detecting exoplanets

1° Radial velocity

A star with a planet will move in its own small orbit in response to the planet’s gravity. This leads to variations in the speed with which the star moves toward or away from Earth, i.e. the variations are in the radial velocity of the star with respect to Earth. The radial velocity can be deduced from the displacement in the parent star’s spectral lines due to the Doppler effect. The radial-velocity method measures these variations in order to confirm the presence of the planet using the binary mass function.

2º Transit photometry

While the radial velocity method provides information about a planet’s mass, the photometric method can determine the planet’s radius. If a planet crosses (transits) in front of its parent star’s disk, then the observed visual brightness of the star drops by a small amount; depending on the relative sizes of the star and the planet.

3° Direct Imaging

Exoplanets are far away, and they are millions of times dimmer than the stars they orbit. So, unsurprisingly, taking pictures of them the same way you’d take pictures of, say Jupiter or Venus, is exceedingly hard.

New techniques and rapidly-advancing technology are making it happen.

The major problem astronomers face in trying to directly image exoplanets is that the stars they orbit are millions of times brighter than their planets. Any light reflected off of the planet or heat radiation from the planet itself is drowned out by the massive amounts of radiation coming from its host star. It’s like trying to find a flea in a lightbulb, or a firefly flitting around a spotlight.

On a bright day, you might use a pair of sunglasses, or a car’s sun visor, or maybe just your hand to block the glare of the sun so that you can see other things.

This is the same principle behind the instruments designed to directly image exoplanets. They use various techniques to block out the light of stars that might have planets orbiting them. Once the glare of the star is reduced, they can get a better look at objects around the star that might be exoplanets.

4° Gravitational Microlensing

Gravitational microlensing occurs when the gravitational field of a star acts like a lens, magnifying the light of a distant background star. This effect occurs only when the two stars are almost exactly aligned. Lensing events are brief, lasting for weeks or days, as the two stars and Earth are all moving relative to each other. More than a thousand such events have been observed over the past ten years.

If the foreground lensing star has a planet, then that planet’s own gravitational field can make a detectable contribution to the lensing effect. Since that requires a highly improbable alignment, a very large number of distant stars must be continuously monitored in order to detect planetary microlensing contributions at a reasonable rate. This method is most fruitful for planets between Earth and the center of the galaxy, as the galactic center provides a large number of background stars.

5° Astrometry

This method consists of precisely measuring a star’s position in the sky, and observing how that position changes over time. Originally, this was done visually, with hand-written records. By the end of the 19th century, this method used photographic plates, greatly improving the accuracy of the measurements as well as creating a data archive. If a star has a planet, then the gravitational influence of the planet will cause the star itself to move in a tiny circular or elliptical orbit.

Effectively, star and planet each orbit around their mutual centre of mass (barycenter), as explained by solutions to the two-body problem. Since the star is much more massive, its orbit will be much smaller. Frequently, the mutual centre of mass will lie within the radius of the larger body. Consequently, it is easier to find planets around low-mass stars, especially brown dwarfs.

source

source (+ Methods of detecting exoplanets)

source

images: NASA/ESA, ESO

animations: x, x, x, x, x

+ Exoplanets

Some intriguing exoplanets

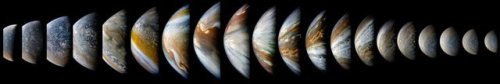

Swirls of Jupiter

Jupiter is a very stormy, turbulent, violent planet. The planet completes a day (or one complete rotation) within roughly 10 hours, which creates massive winds, producing these swirls, and violent storms. The fast rotation coupled with the fact that the planet is nothing but gas greatly multiplies the Coriolis effect. Earth too has a Coriolis effect, this creates the characteristic hurricane shapes and also contributes to the fact that storms will spin the opposite direction in different hemispheres. Luckily, our rotation is slower - our storms are less frequent and less violent than they would be if our days were shorter.

The above images come from the recent Juno mission by NASA.

All Cats Are Beautiful

This Is What The Milky Way’s Magnetic Field Looks Like

“The Milky Way’s gas, dust, stars and more create fascinating, measurable structures. Subtracting out all the foregrounds yields the cosmic background signal, which possesses tiny temperature imperfections. But the galactic foreground isn’t useless; it’s a map unto itself. All background light gets polarized by these foregrounds, enabling the reconstruction of our galaxy’s magnetic field.”

Have you ever wondered what our galaxy’s magnetic field looks like? As long as we restrict ourselves to looking in the type of light that human eyes can see, the optical portion of the spectrum, we’re extremely limited as far as what we can infer. However, if we move on to data from the microwave portion of the spectrum, and in particular we look at the data that comes from the polarization of background light (and the foreground light directly), we should be able to reconstruct our galaxy’s magnetic fields to the best precision ever. The Planck satellite, in addition to mapping the CMB to better precision than ever before, has enabled us to do exactly that.

Even though there are still some small questions and uncertainties, you won’t want to miss these incredible pictures that showcase just how far we’ve come!

The Summer Solstice Has Arrived!

This year’s summer solstice for the northern hemisphere arrives at 11:54 a.m. EDT, meaning today is the longest day of the year! The number of daylight hours varies by latitude, so our headquarters in Washington, D.C. will see 14 hours, 53 minutes, and 51 seconds of daylight. A lot can happen in that time! Let’s find out more.

If you’re spending the day outside, you might be in the path of our Earth Science Satellite Fleet (ESSF)! The fleet, made up of over a dozen Earth observation satellites, will pass over the continental United States about 37 times during today’s daylight hours.

These missions collect data on atmospheric chemistry and composition, cloud cover, ocean levels, climate, ecosystem dynamics, precipitation, and glacial movement, among other things. They aim to do everything from predicting extreme weather to helping informing the public and decision makers with the environment through GPS and imaging. Today, their sensors will send back over 200 gigabytes (GB) of data back to the ground by sunset.

As the sun sets today, the International Space Station (ISS) will be completing its 10th orbit since sunrise. In that time, a little more than 1 terabyte-worth of data will be downlinked to Earth.

That number encompasses data from ground communications, payloads, experiments, and control and navigation signals for the station. Approximately 330 GB of that TB is video, including live broadcasts and downlinks with news outlets. But as recently-returned astronaut Serena Auñón-Chancellor likes to point out, there’s still room for fun. The astronauts aboard the ISS can request YouTube videos or movies for what she likes to call “family movie night.”

Astronauts aboard the station also send back images—LOTS of them. Last year, astronauts sent back an average of 66,912 images per month! During today’s long hours of daylight, we expect the crew to send back about 656 images. But with Expedition 59 astronauts David Saint-Jacques (CSA), Anne McClain (NASA), and Oleg Kononenko (RKA) hard at work preparing to return to Earth on Monday, that number might be a little less.

Say you’re feeling left out after seeing the family dinners and want to join the crew. Would you have enough daylight to travel to the ISS and back on the longest day of the year? Yes, but only if you’re speedy enough, and plan your launch just right. With the current fastest launch-to-docking time of about six hours, you could complete two-and-a-half flights to the ISS today between sunrise and sunset.

When returning from orbit, it’s a longer ordeal. After the Expedition 59 trio arrives on Earth Monday night, they’ll have to travel from Kazakhstan to Houston to begin their post-flight activities. Their journey should take about 18 hours and 30 minutes, just a few hours longer than the hours of daylight we’ll see today.

Happy solstice! Make sure to tune in with us on Monday night for live coverage of the return of Expedition 59. Until then, enjoy the longest day of the year!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

A Tiny Satellite Studies Stormy Layers

The gif above shows data taken by an experimental weather satellite of Hurricane Dorian on September 3, 2019. TEMPEST-D, a NASA CubeSat, reveals rain bands in four layers of the storm by taking the data in four different radio frequencies. The multiple vertical layers show where the most warm, wet air within the hurricane is rising high into the atmosphere. Pink, red and yellow show the areas of heaviest rainfall, while the least intense areas of rainfall are in green and blue.

How does an Earth satellite the size of a cereal box help NASA monitor storms?

The goal of the TEMPEST-D (Temporal Experiment for Storms and Tropical Systems Demonstration) mission is to demonstrate the performance of a CubeSat designed to study precipitation events on a global scale.

If TEMPEST-D can successfully track storms like Dorian, the technology demonstration could lead to a train of small satellites that work together to track storms around the world. By measuring the evolution of clouds from the moment of the start of precipitation, a TEMPEST constellation mission, collecting multiple data points over short periods of time, would improve our understanding of cloud processes and help to clear up one of the largest sources of uncertainty in climate models. Knowledge of clouds, cloud processes and precipitation is essential to our understanding of climate change.

What is a CubeSat, anyway? And what’s the U for?

CubeSats are small, modular, customizable vessels for satellites. They come in single units a little larger than a rubix cube - 10cmx10cmx10cm - that can be stacked in multiple different configurations. One CubeSat is 1U. A CubeSat like TEMPEST-D, which is a 6U, has, you guessed it, six CubeSat units in it.

Pictured above is a full-size mockup of MarCO, a 6U CubeSat that recently went to Mars with the Insight mission. They really are about the size of a cereal box!

We are using CubeSats to test new technologies and push the boundaries of Earth Science in ways never before imagined. CubeSats are much less expensive to produce than traditional satellites; in multiples they could improve our global storm coverage and forecasting data.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

(Source)

A high-definition video camera outside the space station captured stark and sobering views of Hurricane Florence, a Category 4 storm. Image Credit: ESA/NASA–A. Gerst

The scene is a late-spring afternoon in the Amazonis Planitia region of northern Mars. The view covers an area about four-tenths of a mile (644 meters) across. North is toward the top. The length of the dusty whirlwind’s shadow indicates that the dust plume reaches more than half a mile (800 meters) in height. The plume is about 30 yards or meters in diameter. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona

A false-color image of the Great Red Spot of Jupiterfrom Voyager 1. The white oval storm directly below the Great Red Spot has the approximate diameter of Earth. NASA, Caltech/JPL

The huge storm (great white spot) churning through the atmosphere in Saturn’s northern hemisphere overtakes itself as it encircles the planet in this true-color view from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, SSI, JPL, ESA, NASA; Color Composite: Jean-Luc Dauvergne

The spinning vortex of Saturn’s north polar storm resembles a deep red rose of giant proportions surrounded by green foliage in this false-color image from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Measurements have sized the eye at 1,250 miles (2,000 kilometers) across with cloud speeds as fast as 330 miles per hour (150 meters per second). This image is among the first sunlit views of Saturn’s north pole captured by Cassini’s imaging cameras. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

Colorized infrared image of Uranus obtained on August 6, 2014, with adaptive optics on the 10-meter Keck telescope; white spots are large storms. Image credit: Imke de Pater, University of California, Berkeley / Keck Observatory images.

Neptune’s Great Dark Spot, a large anticyclonic storm similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, observed by NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1989. Credit: NASA / Jet Propulsion Lab

This true color image captured by NASA’S Cassini spacecraft before a distant flyby of Saturn’s moon Titan on June 27, 2012, shows a south polar vortex, or a swirling mass of gas around the pole in the atmosphere. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

This artist’s concept shows what the weather might look like on cool star-like bodies known as brown dwarfs. These giant balls of gas start out life like stars, but lack the mass to sustain nuclear fusion at their cores, and instead, fade and cool with time.

New research from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope suggests that most brown dwarfs are racked with colossal storms akin to Jupiter’s famous “Great Red Spot.” These storms may be marked by fierce winds, and possibly lightning. The turbulent clouds might also rain down molten iron, hot sand or salts – materials thought to make up the cloud layers of brown dwarfs.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Western Ontario/Stony Brook University

In this image, the nightmare world of HD 189733 b is the killer you never see coming. To the human eye, this far-off planet looks bright blue. But any space traveler confusing it with the friendly skies of Earth would be badly mistaken. The weather on this world is deadly. Its winds blow up to 5,400 mph (2 km/s) at seven times the speed of sound, whipping all would-be travelers in a sickening spiral around the planet. And getting caught in the rain on this planet is more than an inconvenience; it’s death by a thousand cuts. This scorching alien world possibly rains glass—sideways—in its howling winds. The cobalt blue color comes not from the reflection of a tropical ocean, as on Earth, but rather a hazy, blow-torched atmosphere containing high clouds laced with silicate particles. Image Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

cosmic microwave background

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is electromagnetic radiation as a remnant from an early stage of the universe in Big Bang cosmology. In older literature, the CMB is also variously known as cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR) or “relic radiation”. The CMB is a faint cosmic background radiation filling all space that is an important source of data on the early universe because it is the oldest electromagnetic radiation in the universe, dating to the epoch of recombination.

With a traditional optical telescope, the space between stars and galaxies (the background) is completely dark. However, a sufficiently sensitive radio telescope shows a faint background noise, or glow, almost isotropic, that is not associated with any star, galaxy, or other object. This glow is strongest in the microwave region of the radio spectrum. The accidental discovery of the CMB in 1964 by American radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson was the culmination of work initiated in the 1940s, and earned the discoverers the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics.

The discovery of CMB is landmark evidence of the Big Bang origin of the universe. When the universe was young, before the formation of stars and planets, it was denser, much hotter, and filled with a uniform glow from a white-hot fog of hydrogen plasma. As the universe expanded, both the plasma and the radiation filling it grew cooler. When the universe cooled enough, protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen atoms. Unlike the uncombined protons and electrons, these newly conceived atoms could not absorb the thermal radiation, and so the universe became transparent instead of being an opaque fog. Cosmologists refer to the time period when neutral atoms first formed as the recombination epoch, and the event shortly afterwards when photons started to travel freely through space rather than constantly being scattered by electrons and protons in plasma is referred to as photon decoupling.

Basically, cosmic microwave background radiation is the fossil of light, resulting from a time when the Universe was hot and dense, only 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Cosmic microwave background radiation is an electromagnetic radiation that fills the entire universe, whose spectrum is that of a blackbody at a temperature of 2.725 kelvin.

Cosmic microwave background radiation, along with the spacing from galaxies and the abundance of light elements, is one of the strongest observational evidences of the Big Bang model, which describes the evolution of the universe. Penzias and Wilson received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978 for this discovery

source, source in portuguese

images credit: Image credit: Institute of Astronomy / National Tsing Hua University/ NASA/ESA Hubble, wikipedia

Why 2020 Might Be The Best Geminid Meteor Shower Of All-Time

“As the large parent body of the Geminids, asteroid 3200 Phaethon, continues on its tight orbit around the Sun, it will continue to expel matter and be torn apart, bit by tiny bit. The asteroid is about the size of the one that struck Earth 65 million years ago, causing our last great mass extinction. But instead of colliding with us all at once, this ~6 km wide asteroid is slowly dissipating in the presence of the Sun, creating tails of matter and ions but also an ever-thickening debris stream.

With each mid-December that rolls past, Earth slams through that debris stream, creating a show that gets progressively more spectacular with each set of orbits that regularly tick by. Over the past 15 years, the Geminids have regularly been one of the two best displays of meteor showers on Earth, and it’s eminently possible that 2020 will set a new record. The Moon, the Earth, and all of the other predictable conditions are just right for a spectacular show. If the clouds cooperate on December 13 and 14, treat yourself to the greatest natural show of the year. With all that 2020 has brought us, we can all use a cosmic treat like this one.”

Can everyone just have a good thing to enjoy? Can we all just have something nice that we don’t have to fight over? Well, nature might deliver what humanity has been unable to bring us for 2020: a natural show that can’t be stopped by anything, except for clouds.

Get your Geminid fix today, and then look up on December 13/14 to fully enjoy the show!

-

misan-thropist reblogged this · 2 years ago

misan-thropist reblogged this · 2 years ago -

zhouzihengs reblogged this · 5 years ago

zhouzihengs reblogged this · 5 years ago -

dankeldre liked this · 5 years ago

dankeldre liked this · 5 years ago -

delicioushorseweaselpie liked this · 5 years ago

delicioushorseweaselpie liked this · 5 years ago -

supersaiyn3232 liked this · 5 years ago

supersaiyn3232 liked this · 5 years ago -

newmarinette liked this · 5 years ago

newmarinette liked this · 5 years ago -

miguelfavgf liked this · 5 years ago

miguelfavgf liked this · 5 years ago -

fraktally reblogged this · 5 years ago

fraktally reblogged this · 5 years ago -

thavinceman reblogged this · 5 years ago

thavinceman reblogged this · 5 years ago -

thavinceman liked this · 5 years ago

thavinceman liked this · 5 years ago -

sanjerodo liked this · 5 years ago

sanjerodo liked this · 5 years ago -

laws-axioms reblogged this · 5 years ago

laws-axioms reblogged this · 5 years ago -

oneiridescent liked this · 5 years ago

oneiridescent liked this · 5 years ago -

astronomerosh19 reblogged this · 5 years ago

astronomerosh19 reblogged this · 5 years ago -

astronomerosh19 liked this · 5 years ago

astronomerosh19 liked this · 5 years ago -

n0-name-gypsy reblogged this · 5 years ago

n0-name-gypsy reblogged this · 5 years ago -

rosaspinaciao-blog liked this · 5 years ago

rosaspinaciao-blog liked this · 5 years ago -

heartbreakcase liked this · 5 years ago

heartbreakcase liked this · 5 years ago -

birdflu2k11 liked this · 5 years ago

birdflu2k11 liked this · 5 years ago -

pmc8 liked this · 5 years ago

pmc8 liked this · 5 years ago -

loaiza-2308-blog liked this · 5 years ago

loaiza-2308-blog liked this · 5 years ago -

millerscritters reblogged this · 5 years ago

millerscritters reblogged this · 5 years ago -

gnifrus reblogged this · 5 years ago

gnifrus reblogged this · 5 years ago -

gnifrus liked this · 5 years ago

gnifrus liked this · 5 years ago -

hicksterman reblogged this · 5 years ago

hicksterman reblogged this · 5 years ago -

migmatites-blog liked this · 5 years ago

migmatites-blog liked this · 5 years ago -

geologyandstuff reblogged this · 5 years ago

geologyandstuff reblogged this · 5 years ago -

breatheandreset liked this · 5 years ago

breatheandreset liked this · 5 years ago -

death-by-physics liked this · 5 years ago

death-by-physics liked this · 5 years ago -

oldnoname5 reblogged this · 5 years ago

oldnoname5 reblogged this · 5 years ago -

geo-geralt liked this · 5 years ago

geo-geralt liked this · 5 years ago -

silpion01 liked this · 5 years ago

silpion01 liked this · 5 years ago -

ambraj reblogged this · 5 years ago

ambraj reblogged this · 5 years ago -

ambraj liked this · 5 years ago

ambraj liked this · 5 years ago -

blacktar17 liked this · 5 years ago

blacktar17 liked this · 5 years ago -

kalem-maelor reblogged this · 5 years ago

kalem-maelor reblogged this · 5 years ago -

pitchsilent liked this · 5 years ago

pitchsilent liked this · 5 years ago -

jonnieboiijr liked this · 5 years ago

jonnieboiijr liked this · 5 years ago -

truthofthesignal liked this · 5 years ago

truthofthesignal liked this · 5 years ago