FOR SALE: Mobile &Web Illustration

FOR SALE: Mobile &Web Illustration

More Posts from Ocrim1967 and Others

Couple goals

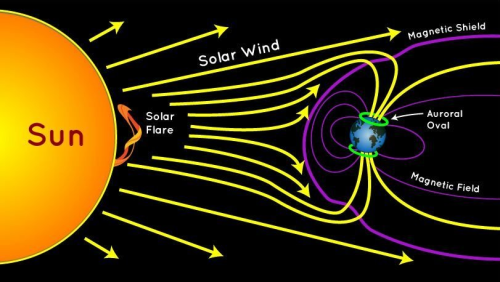

Stellar Winds

Stellar winds are fast moving flows of material (protons, electrons and atoms of heavier metals) that are ejected from stars. These winds are characterised by a continuous outflow of material moving at speeds anywhere between 20 and 2,000 km/s.

In the case of the Sun, the wind ‘blows’ at a speed of 200 to 300 km/s from quiet regions, and 700 km/s from coronal holes and active regions.

The causes, ejection rates and speeds of stellar winds vary with the mass of the star. In relatively cool, low-mass stars such as the Sun, the wind is caused by the extremely high temperature (millions of degrees Kelvin) of the corona.

his high temperature is thought to be the result of interactions between magnetic fields at the star’s surface, and gives the coronal gas sufficient energy to escape the gravitational attraction of the star as a wind. Stars of this type eject only a tiny fraction of their mass per year as a stellar wind (for example, only 1 part in 1014 of the Sun’s mass is ejected in this way each year), but this still represents losses of millions of tonnes of material each second. Even over their entire lifetime, stars like our Sun lose only a tiny fraction of 1% of their mass through stellar winds.

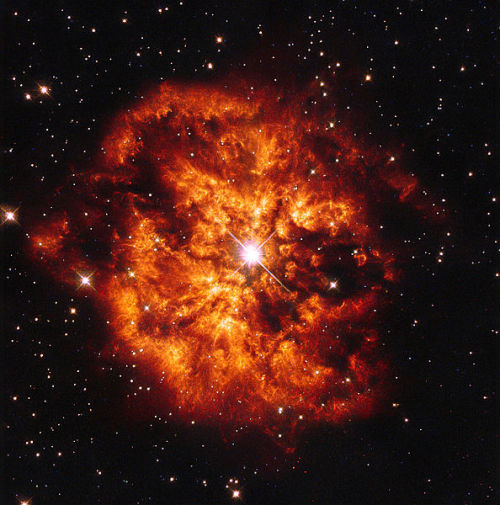

In contrast, hot, massive stars can produce stellar winds a billion times stronger than those of low-mass stars. Over their short lifetimes, they can eject many solar masses (perhaps up to 50% of their initial mass) of material in the form of 2,000 km/sec winds.

These stellar winds are driven directly by the radiation pressure from photons escaping the star. In some cases, high-mass stars can eject virtually all of their outer envelopes in winds. The result is a Wolf-Rayet star.

Stellar winds play an important part in the chemical evolution of the Universe, as they carry dust and metals back into the interstellar medium where they will be incorporated into the next generation of stars.

source (read more) + Wolf–Rayet star

(Source)

This Is How The Universe Changes With Every New Year That Passes

“With an 13.8 billion year lifetime so far, the Universe has certainly been around for some time. While it may seem to change only imperceptibly on human timescales, the fact remains that these changes are real, important, and cumulative. If we look closely and precisely enough, we can observe these changes on timescales as small as a single year.

These changes affect not only our home world, but our Solar System, galaxy, and even the entire Universe. We are only in the beginning stages of exploring how the Universe changes over time and what it looks like at the greatest distances and faintest extremes. May the 2020s mark the decade, at long last, where we pool our efforts as a species into the endeavor to uncover the greatest cosmic secrets of all.”

With every year that goes by, tiny, imperceptible changes occur in our physical Universe that really add up over time. The Earth’s rotation is slowing, the Moon is spiraling outwards, the Sun is heating up and new stars are forming. On a cosmic scale, the Universe is expanding and getting cooler, and more galaxies are becoming visible while fewer stars are capable of being visited.

This is how the Universe changes with each new year that passes, and we can quantify the effects today!

Black Holes are NICER Than You Think!

We’re learning more every day about black holes thanks to one of the instruments aboard the International Space Station! Our Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) instrument is keeping an eye on some of the most mysterious cosmic phenomena.

We’re going to talk about some of the amazing new things NICER is showing us about black holes. But first, let’s talk about black holes — how do they work, and where do they come from? There are two important types of black holes we’ll talk about here: stellar and supermassive. Stellar mass black holes are three to dozens of times as massive as our Sun while supermassive black holes can be billions of times as massive!

Stellar black holes begin with a bang — literally! They are one of the possible objects left over after a large star dies in a supernova explosion. Scientists think there are as many as a billion stellar mass black holes in our Milky Way galaxy alone!

Supermassive black holes have remained rather mysterious in comparison. Data suggest that supermassive black holes could be created when multiple black holes merge and make a bigger one. Or that these black holes formed during the early stages of galaxy formation, born when massive clouds of gas collapsed billions of years ago. There is very strong evidence that a supermassive black hole lies at the center of all large galaxies, as in our Milky Way.

Imagine an object 10 times more massive than the Sun squeezed into a sphere approximately the diameter of New York City — or cramming a billion trillion people into a car! These two examples give a sense of how incredibly compact and dense black holes can be.

Because so much stuff is squished into such a relatively small volume, a black hole’s gravity is strong enough that nothing — not even light — can escape from it. But if light can’t escape a dark fate when it encounters a black hole, how can we “see” black holes?

Scientists can’t observe black holes directly, because light can’t escape to bring us information about what’s going on inside them. Instead, they detect the presence of black holes indirectly — by looking for their effects on the cosmic objects around them. We see stars orbiting something massive but invisible to our telescopes, or even disappearing entirely!

When a star approaches a black hole’s event horizon — the point of no return — it’s torn apart. A technical term for this is “spaghettification” — we’re not kidding! Cosmic objects that go through the process of spaghettification become vertically stretched and horizontally compressed into thin, long shapes like noodles.

Scientists can also look for accretion disks when searching for black holes. These disks are relatively flat sheets of gas and dust that surround a cosmic object such as a star or black hole. The material in the disk swirls around and around, until it falls into the black hole. And because of the friction created by the constant movement, the material becomes super hot and emits light, including X-rays.

At last — light! Different wavelengths of light coming from accretion disks are something we can see with our instruments. This reveals important information about black holes, even though we can’t see them directly.

So what has NICER helped us learn about black holes? One of the objects this instrument has studied during its time aboard the International Space Station is the ever-so-forgettably-named black hole GRS 1915+105, which lies nearly 36,000 light-years — or 200 million billion miles — away, in the direction of the constellation Aquila.

Scientists have found disk winds — fast streams of gas created by heat or pressure — near this black hole. Disk winds are pretty peculiar, and we still have a lot of questions about them. Where do they come from? And do they change the shape of the accretion disk?

It’s been difficult to answer these questions, but NICER is more sensitive than previous missions designed to return similar science data. Plus NICER often looks at GRS 1915+105 so it can see changes over time.

NICER’s observations of GRS 1915+105 have provided astronomers a prime example of disk wind patterns, allowing scientists to construct models that can help us better understand how accretion disks and their outflows around black holes work.

NICER has also collected data on a stellar mass black hole with another long name — MAXI J1535-571 (we can call it J1535 for short) — adding to information provided by NuSTAR, Chandra, and MAXI. Even though these are all X-ray detectors, their observations tell us something slightly different about J1535, complementing each other’s data!

This rapidly spinning black hole is part of a binary system, slurping material off its partner, a star. A thin halo of hot gas above the disk illuminates the accretion disk and causes it to glow in X-ray light, which reveals still more information about the shape, temperature, and even the chemical content of the disk. And it turns out that J1535’s disk may be warped!

Image courtesy of NRAO/AUI and Artist: John Kagaya (Hoshi No Techou)

This isn’t the first time we have seen evidence for a warped disk, but J1535’s disk can help us learn more about stellar black holes in binary systems, such as how they feed off their companions and how the accretion disks around black holes are structured.

NICER primarily studies neutron stars — it’s in the name! These are lighter-weight relatives of black holes that can be formed when stars explode. But NICER is also changing what we know about many types of X-ray sources. Thanks to NICER’s efforts, we are one step closer to a complete picture of black holes. And hey, that’s pretty nice!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

The Scorpii AR system

In the system AR Scorpii a rapidly spinning white dwarf star powers electrons up to almost the speed of light. These high energy particles release blasts of radiation that lash the companion red dwarf star, and cause the entire system to pulse dramatically every 1.97 minutes with radiation ranging from the ultraviolet to radio.

The star system AR Scorpii, or AR Sco for short, lies in the constellation of Scorpius, 380 light-years from Earth. It comprises a rapidly spinning white dwarf, the size of Earth but containing 200,000 times more mass, and a cool red dwarf companion one third the mass of the Sun, orbiting one another every 3.6 hours in a cosmic dance as regular as clockwork.

Read more at: cosmosmagazine & astronomynow

NASA’s New Planet Hunter Reveals a Sky Full of Stars

NASA’s newest planet-hunting satellite — the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS for short — has just released its first science image using all of its cameras to capture a huge swath of the sky! TESS is NASA’s next step in the search for planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets.

This spectacular image, the first released using all four of TESS’ cameras, shows the satellite’s full field of view. It captures parts of a dozen constellations, from Capricornus (the Sea Goat) to Pictor (the Painter’s Easel) — though it might be hard to find familiar constellations among all these stars! The image even includes the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, our galaxy’s two largest companion galaxies.

The science community calls this image “first light,” but don’t let that fool you — TESS has been seeing light since it launched in April. A first light image like this is released to show off the first science-quality image taken after a mission starts collecting science data, highlighting a spacecraft’s capabilities.

TESS has been busy since it launched from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. First TESS needed to get into position, which required a push from the Moon. After nearly a month in space, the satellite passed about 5,000 miles from the Moon, whose gravity gave it the boost it needed to get into a special orbit that will keep it stable and maximize its view of the sky.

During those first few weeks, we also got a sneak peek of the sky through one of TESS’s four cameras. This test image captured over 200,000 stars in just two seconds! The spacecraft was pointed toward the constellation Centaurus when it snapped this picture. The bright star Beta Centauri is visible at the lower left edge, and the edge of the Coalsack Nebula is in the right upper corner.

After settling into orbit, scientists ran a number of checks on TESS, including testing its ability to collect a set of stable images over a prolonged period of time. TESS not only proved its ability to perform this task, it also got a surprise! A comet named C/2018 N1 passed through TESS’s cameras for about 17 hours in July.

The images show a treasure trove of cosmic curiosities. There are some stars whose brightness changes over time and asteroids visible as small moving white dots. You can even see an arc of stray light from Mars, which is located outside the image, moving across the screen.

Now that TESS has settled into orbit and has been thoroughly tested, it’s digging into its main mission of finding planets around other stars. How will it spot something as tiny and faint as a planet trillions of miles away? The trick is to look at the star!

So far, most of the exoplanets we’ve found were detected by looking for tiny dips in the brightness of their host stars. These dips are caused by the planet passing between us and its star – an event called a transit. Over its first two years, TESS will stare at 200,000 of the nearest and brightest stars in the sky to look for transits to identify stars with planets.

TESS will be building on the legacy of NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which also used transits to find exoplanets. TESS’s target stars are about 10 times closer than Kepler’s, so they’ll tend to be brighter. Because they’re closer and brighter, TESS’s target stars will be ideal candidates for follow-up studies with current and future observatories.

TESS is challenging over 200,000 of our stellar neighbors to a staring contest! Who knows what new amazing planets we’ll find?

The TESS mission is led by MIT and came together with the help of many different partners. You can keep up with the latest from the TESS mission by following mission updates.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

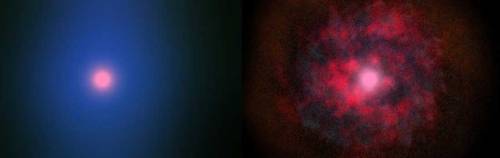

cosmic microwave background

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is electromagnetic radiation as a remnant from an early stage of the universe in Big Bang cosmology. In older literature, the CMB is also variously known as cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR) or “relic radiation”. The CMB is a faint cosmic background radiation filling all space that is an important source of data on the early universe because it is the oldest electromagnetic radiation in the universe, dating to the epoch of recombination.

With a traditional optical telescope, the space between stars and galaxies (the background) is completely dark. However, a sufficiently sensitive radio telescope shows a faint background noise, or glow, almost isotropic, that is not associated with any star, galaxy, or other object. This glow is strongest in the microwave region of the radio spectrum. The accidental discovery of the CMB in 1964 by American radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson was the culmination of work initiated in the 1940s, and earned the discoverers the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics.

The discovery of CMB is landmark evidence of the Big Bang origin of the universe. When the universe was young, before the formation of stars and planets, it was denser, much hotter, and filled with a uniform glow from a white-hot fog of hydrogen plasma. As the universe expanded, both the plasma and the radiation filling it grew cooler. When the universe cooled enough, protons and electrons combined to form neutral hydrogen atoms. Unlike the uncombined protons and electrons, these newly conceived atoms could not absorb the thermal radiation, and so the universe became transparent instead of being an opaque fog. Cosmologists refer to the time period when neutral atoms first formed as the recombination epoch, and the event shortly afterwards when photons started to travel freely through space rather than constantly being scattered by electrons and protons in plasma is referred to as photon decoupling.

Basically, cosmic microwave background radiation is the fossil of light, resulting from a time when the Universe was hot and dense, only 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Cosmic microwave background radiation is an electromagnetic radiation that fills the entire universe, whose spectrum is that of a blackbody at a temperature of 2.725 kelvin.

Cosmic microwave background radiation, along with the spacing from galaxies and the abundance of light elements, is one of the strongest observational evidences of the Big Bang model, which describes the evolution of the universe. Penzias and Wilson received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978 for this discovery

source, source in portuguese

images credit: Image credit: Institute of Astronomy / National Tsing Hua University/ NASA/ESA Hubble, wikipedia

I love flowers 💐❤️

5 New Competitions for the Artemis Generation!

A common question we get is, “How can I work with NASA?”

The good news is—just in time for the back-to-school season—we have a slew of newly announced opportunities for citizen scientists and researchers in the academic community to take a shot at winning our prize competitions.

As we plan to land humans on the Moon by 2024 with our upcoming Artemis missions, we are urging students and universities to get involved and offer solutions to the challenges facing our path to the Moon and Mars. Here are five NASA competitions and contests waiting for your ideas on everything from innovative ways to drill for water on other planets to naming our next rover:

1. The BIG Idea Challenge: Studying Dark Regions on the Moon

Before astronauts step on the Moon again, we will study its surface to prepare for landing, living and exploring there. Although it is Earth’s closest neighbor, there is still much to learn about the Moon, particularly in the permanently shadowed regions in and near the polar regions.

Through the annual Breakthrough, Innovative and Game-changing (BIG) Idea Challenge, we’re asking undergraduate and graduate student teams to submit proposals for sample lunar payloads that can demonstrate technology systems needed to explore areas of the Moon that never see the light of day. Teams of up to 20 students and their faculty advisors are invited to propose unique solutions in response to one of the following areas:

• Exploration of permanently shadowed regions in lunar polar regions • Technologies to support in-situ resource utilization in these regions • Capabilities to explore and operate in permanently shadowed regions

Interested teams are encouraged to submit a Notice of Intent by September 27 in order to ensure an adequate number of reviewers and to be invited to participate in a Q&A session with the judges prior to the proposal deadline. Proposal and video submission are due by January 16, 2020.

2. RASC-AL 2020: New Concepts for the Moon and Mars

Although boots on the lunar surface by 2024 is step one in expanding our presence beyond low-Earth orbit, we’re also readying our science, technology and human exploration missions for a future on Mars.

The 2020 Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concepts – Academic Linkage (RASC-AL) Competition is calling on undergraduate and graduate teams to develop new concepts that leverage innovations for both our Artemis program and future human missions to the Red Planet. This year’s competition branches beyond science and engineering with a theme dedicated to economic analysis of commercial opportunities in deep space.

Competition themes range from expanding on how we use current and future assets in cislunar space to designing systems and architectures for exploring the Moon and Mars. We’re seeking proposals that demonstrate originality and creativity in the areas of engineering and analysis and must address one of the five following themes: a south pole multi-purpose rover, the International Space Station as a Mars mission analog, short surface stay Mars mission, commercial cislunar space development and autonomous utilization and maintenance on the Gateway or Mars-class transportation.

The RASC-AL challenge is open to undergraduate and graduate students majoring in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics at an accredited U.S.-based university. Submissions are due by March 5, 2020 and must include a two-minute video and a detailed seven to nine-page proposal that presents novel and robust applications that address one of the themes and support expanding humanity’s ability to thrive beyond Earth.

3. The Space Robotics Challenge for Autonomous Rovers

Autonomous robots will help future astronauts during long-duration missions to other worlds by performing tedious, repetitive and even strenuous tasks. These robotic helpers will let crews focus on the more meticulous areas of exploring. To help achieve this, our Centennial Challenges initiative, along with Space Center Houston of Texas, opened the second phase of the Space Robotics Challenge. This virtual challenge aims to advance autonomous robotic operations for missions on the surface of distant planets or moons.

This new phase invites competitors 18 and older from the public, industry and academia to develop code for a team of virtual robots that will support a simulated in-situ resource utilization mission—meaning gathering and using materials found locally—on the Moon.

The deadline to submit registration forms is December 20.

4. Moon to Mars Ice & Prospecting Challenge to Design Hardware, Practice Drilling for Water on the Moon and Mars

A key ingredient for our human explorers staying anywhere other than Earth is water. One of the most crucial near-term plans for deep space exploration includes finding and using water to support a sustained presence on our nearest neighbor and on Mars.

To access and extract that water, NASA needs new technologies to mine through various layers of lunar and Martian dirt and into ice deposits we believe are buried beneath the surface. A special edition of the RASC-AL competition, the Moon to Mars Ice and Prospecting Challenge, seeks to advance critical capabilities needed on the surface of the Moon and Mars. The competition, now in its fourth iteration, asks eligible undergraduate and graduate student teams to design and build hardware that can identify, map and drill through a variety of subsurface layers, then extract water from an ice block in a simulated off-world test bed.

Interested teams are asked to submit a project plan detailing their proposed concept’s design and operations by November 14. Up to 10 teams will be selected and receive a development stipend. Over the course of six months teams will build and test their systems in preparation for a head-to-head competition at our Langley Research Center in June 2020.

5. Name the Mars 2020 Rover!

Red rover, red rover, send a name for Mars 2020 right over! We’re recruiting help from K-12 students nationwide to find a name for our next Mars rover mission.

The Mars 2020 rover is a 2,300-pound robotic scientist that will search for signs of past microbial life, characterize the planet’s climate and geology, collect samples for future return to Earth, and pave the way for human exploration of the Red Planet.

K-12 students in U.S. public, private and home schools can enter the Mars 2020 Name the Rover essay contest. One grand prize winner will name the rover and be invited to see the spacecraft launch in July 2020 from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. To enter the contest, students must submit by November 1 their proposed rover name and a short essay, no more than 150 words, explaining why their proposed name should be chosen.

Just as the Apollo program inspired innovation in the 1960s and ‘70s, our push to the Moon and Mars is inspiring students—the Artemis generation—to solve the challenges for the next era of space exploration.

For more information on all of our open prizes and challenges, visit: https://www.nasa.gov/solve/explore_opportunities

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

-

sammcnoise liked this · 6 years ago

sammcnoise liked this · 6 years ago -

interactivefactory liked this · 6 years ago

interactivefactory liked this · 6 years ago -

johnny-pixel reblogged this · 6 years ago

johnny-pixel reblogged this · 6 years ago -

milltee liked this · 6 years ago

milltee liked this · 6 years ago -

myhellocn liked this · 6 years ago

myhellocn liked this · 6 years ago -

crazycatillustrations reblogged this · 6 years ago

crazycatillustrations reblogged this · 6 years ago -

hablachecho reblogged this · 6 years ago

hablachecho reblogged this · 6 years ago -

7luck liked this · 6 years ago

7luck liked this · 6 years ago -

ocrim1967 reblogged this · 6 years ago

ocrim1967 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

ocrim1967 liked this · 6 years ago

ocrim1967 liked this · 6 years ago -

threesevenfive liked this · 6 years ago

threesevenfive liked this · 6 years ago -

inreylo liked this · 6 years ago

inreylo liked this · 6 years ago -

joheroba liked this · 6 years ago

joheroba liked this · 6 years ago -

meliodas-odragraodaira liked this · 6 years ago

meliodas-odragraodaira liked this · 6 years ago -

webdesignshopping reblogged this · 6 years ago

webdesignshopping reblogged this · 6 years ago