Galaxies: Types And Morphology

Galaxies: Types and morphology

A galaxy is a gravitationally bound system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, and dark matter. Galaxies range in size from dwarfs with just a few hundred million (108) stars to giants with one hundred trillion (1014) stars, each orbiting its galaxy’s center of mass.

Galaxies come in three main types: ellipticals, spirals, and irregulars. A slightly more extensive description of galaxy types based on their appearance is given by the Hubble sequence.

Since the Hubble sequence is entirely based upon visual morphological type (shape), it may miss certain important characteristics of galaxies such as star formation rate in starburst galaxies and activity in the cores of active galaxies.

Ellipticals

The Hubble classification system rates elliptical galaxies on the basis of their ellipticity, ranging from E0, being nearly spherical, up to E7, which is highly elongated. These galaxies have an ellipsoidal profile, giving them an elliptical appearance regardless of the viewing angle. Their appearance shows little structure and they typically have relatively little interstellar matter. Consequently, these galaxies also have a low portion of open clusters and a reduced rate of new star formation. Instead they are dominated by generally older, more evolved stars that are orbiting the common center of gravity in random directions.

Spirals

Spiral galaxies resemble spiraling pinwheels. Though the stars and other visible material contained in such a galaxy lie mostly on a plane, the majority of mass in spiral galaxies exists in a roughly spherical halo of dark matter that extends beyond the visible component, as demonstrated by the universal rotation curve concept.

Spiral galaxies consist of a rotating disk of stars and interstellar medium, along with a central bulge of generally older stars. Extending outward from the bulge are relatively bright arms. In the Hubble classification scheme, spiral galaxies are listed as type S, followed by a letter (a, b, or c) that indicates the degree of tightness of the spiral arms and the size of the central bulge.

Barred spiral galaxy

A majority of spiral galaxies, including our own Milky Way galaxy, have a linear, bar-shaped band of stars that extends outward to either side of the core, then merges into the spiral arm structure. In the Hubble classification scheme, these are designated by an SB, followed by a lower-case letter (a, b or c) that indicates the form of the spiral arms (in the same manner as the categorization of normal spiral galaxies).

Ring galaxy

A ring galaxy is a galaxy with a circle-like appearance. Hoag’s Object, discovered by Art Hoag in 1950, is an example of a ring galaxy. The ring contains many massive, relatively young blue stars, which are extremely bright. The central region contains relatively little luminous matter. Some astronomers believe that ring galaxies are formed when a smaller galaxy passes through the center of a larger galaxy. Because most of a galaxy consists of empty space, this “collision” rarely results in any actual collisions between stars.

Lenticular galaxy

A lenticular galaxy (denoted S0) is a type of galaxy intermediate between an elliptical (denoted E) and a spiral galaxy in galaxy morphological classification schemes. They contain large-scale discs but they do not have large-scale spiral arms. Lenticular galaxies are disc galaxies that have used up or lost most of their interstellar matter and therefore have very little ongoing star formation. They may, however, retain significant dust in their disks.

Irregular galaxy

An irregular galaxy is a galaxy that does not have a distinct regular shape, unlike a spiral or an elliptical galaxy. Irregular galaxies do not fall into any of the regular classes of the Hubble sequence, and they are often chaotic in appearance, with neither a nuclear bulge nor any trace of spiral arm structure.

Dwarf galaxy

Despite the prominence of large elliptical and spiral galaxies, most galaxies in the Universe are dwarf galaxies. These galaxies are relatively small when compared with other galactic formations, being about one hundredth the size of the Milky Way, containing only a few billion stars. Ultra-compact dwarf galaxies have recently been discovered that are only 100 parsecs across.

Interacting

Interactions between galaxies are relatively frequent, and they can play an important role in galactic evolution. Near misses between galaxies result in warping distortions due to tidal interactions, and may cause some exchange of gas and dust. Collisions occur when two galaxies pass directly through each other and have sufficient relative momentum not to merge.

Starburst

Stars are created within galaxies from a reserve of cold gas that forms into giant molecular clouds. Some galaxies have been observed to form stars at an exceptional rate, which is known as a starburst. If they continue to do so, then they would consume their reserve of gas in a time span less than the lifespan of the galaxy. Hence starburst activity usually lasts for only about ten million years, a relatively brief period in the history of a galaxy.

Active galaxy

A portion of the observable galaxies are classified as active galaxies if the galaxy contains an active galactic nucleus (AGN). A significant portion of the total energy output from the galaxy is emitted by the active galactic nucleus, instead of the stars, dust and interstellar medium of the galaxy.

The standard model for an active galactic nucleus is based upon an accretion disc that forms around a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at the core region of the galaxy. The radiation from an active galactic nucleus results from the gravitational energy of matter as it falls toward the black hole from the disc. In about 10% of these galaxies, a diametrically opposed pair of energetic jets ejects particles from the galaxy core at velocities close to the speed of light. The mechanism for producing these jets is not well understood.

The main known types are: Seyfert galaxies, quasars, Blazars, LINERS and Radio galaxy.

source

images: NASA/ESA, Hubble (via wikipedia)

More Posts from Evisno and Others

![WATCH: Crystal Birth, A Beautiful Timelapse Of Metallic Crystals Forming In Chemical Solutions [video]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/a6b789bd547bb0fc1e3119df87332f1a/tumblr_oghrhqfMiX1rte5gyo2_500.gif)

![WATCH: Crystal Birth, A Beautiful Timelapse Of Metallic Crystals Forming In Chemical Solutions [video]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/0c08f977f51ba218837b72a94f7bbd69/tumblr_oghrhqfMiX1rte5gyo4_500.gif)

![WATCH: Crystal Birth, A Beautiful Timelapse Of Metallic Crystals Forming In Chemical Solutions [video]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/94f32be0db445db0cdfe2546b015295b/tumblr_oghrhqfMiX1rte5gyo1_500.gif)

![WATCH: Crystal Birth, A Beautiful Timelapse Of Metallic Crystals Forming In Chemical Solutions [video]](https://64.media.tumblr.com/333f1f1da60d5ff8500aa7a751dba6c4/tumblr_oghrhqfMiX1rte5gyo3_500.gif)

WATCH: Crystal Birth, a Beautiful Timelapse of Metallic Crystals Forming in Chemical Solutions [video]

Drops of a liquid can often join a pool gradually through a process known as the coalescence cascade (top left). In this process, a drop sits atop a pool, separated by a thin air layer. Once that air drains out, contact is made and part of the drop coalesces. Then a smaller daughter droplet rebounds and the process repeats.

A recent study describes a related phenomenon (top right) in which the coalescence cascade is drastically sped up through the use of surfactants. The normal cascade depends strongly on the amount of time it takes for the air layer between the drop and pool to drain. By making the pool a liquid with a much greater surface tension value than the drop, the researchers sped up the air layer’s drainage. The mismatch in surface tension between the drop and pool creates an outward flow on the surface (below) due to the Marangoni effect. As the pool’s liquid moves outward, it drags air with it, thereby draining the separating layer more quickly. The result is still a coalescence cascade but one in which the later stages have no rebound and coalesce quickly. (Image and research credit: S. Shim and H. Stone, source)

death of a star by a supernova explosion,

and the birth of a black hole

New supernova likely arose from massive Wolf-Rayet star

They’ve been identified as possible causes for supernovae for a while, but until now, there was a lack of evidence linking massive Wolf-Rayet stars to these star explosions. A new study was able to find a “likely” link between this star type and a supernova called SN 2013cu, however.

“When the supernova exploded, it flash ionized its immediate surroundings, giving the astronomers a direct glimpse of the progenitor star’s chemistry. This opportunity lasts only for a day before the supernovablast wave sweeps the ionization away. So it’s crucial to rapidly respond to a young supernova discovery to get the flash spectrum in the nick of time,” the Carnegie Institution for Science wrote in a statement.

“The observations found evidence of composition and shape that aligns with that of a nitrogen-rich Wolf-Rayet star. What’s more, the progenitor star likely experienced an increased loss of mass shortly before the explosion, which is consistent with model predictions for Wolf-Rayet explosions.”

The star type is known for lacking hydrogen (in comparison to other stars) — which makes it easy to identify spectrally — and being large (upwards of 20 times more massive than our Sun), hot and breezy, with fierce stellar winds that can reach more than 1,000 kilometres per second. This particular supernova was spotted by the Palomar 48-inch telescope in California, and the “likely progenitor” was found about 15 hours after the explosion.

Researchers also noted that the new technique, called “flash spectroscopy”, allows them to look at stars over a range of about 100 megaparsecs or more than 325 million light years — about five times further than what previous observations with the Hubble Space Telescope revealed.

Image credit: ESO

HIV virus particle, budding influenza virus and HIV in blood serum as illustrated by David S. Goodsell.

Goodsell is a professor at the Scripps Research Institute and is widely known for his scientific illustrations of life at a molecular scale. The illustrations are usually based on electron microscopy images and available protein structure data, which makes them more or less accurate. Each month a new illustrated protein structure can be found in Protein Data Bank molecule of the month section and you can read more on how his art is made here.

Solar System: Things to Know This Week

Learn the latest on Cassini’s Grand Finale, Pluto, Hubble Space Telescope and the Red Planet.

1. Cassini’s Grand Finale

After more than 12 years at Saturn, our Cassini mission has entered the final year of its epic voyage to the giant planet and its family of moons. But the journey isn’t over. The upcoming months will be like a whole new mission, with lots of new science and a truly thrilling ride in the unexplored space near the rings. Later this year, the spacecraft will fly repeatedly just outside the rings, capturing the closest views ever. Then, it will actually orbit inside the gap between the rings and the planet’s cloud tops.

Get details on Cassini’s final mission

The von Kármán Lecture Series: 2016

2. Chandra X-Rays Pluto

As the New Horizon’s mission headed to Pluto, our Chandra X-Ray Observatory made the first detection of the planet in X-rays. Chandra’s observations offer new insight into the space environment surrounding the largest and best-known object in the solar system’s outermost regions.

See Pluto’s X-Ray

3. … And Then Pluto Painted the Town Red

When the cameras on our approaching New Horizons spacecraft first spotted the large reddish polar region on Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, mission scientists knew two things: they’d never seen anything like it before, and they couldn’t wait to get the story behind it. After analyzing the images and other data that New Horizons has sent back from its July 2015 flight through the Pluto system, scientists think they’ve solved the mystery. Charon’s polar coloring comes from Pluto itself—as methane gas that escapes from Pluto’s atmosphere and becomes trapped by the moon’s gravity and freezes to the cold, icy surface at Charon’s pole.

Get the details

4. Pretty as a Postcard

The famed red-rock deserts of the American Southwest and recent images of Mars bear a striking similarity. New color images returned by our Curiosity Mars rover reveal the layered geologic past of the Red Planet in stunning detail.

More images

5. Things Fall Apart

Our Hubble Space Telescope recently observed a comet breaking apart. In a series of images taken over a three-day span in January 2016, Hubble captured images of 25 building-size blocks made of a mixture of ice and dust drifting away from the comet. The resulting debris is now scattered along a 3,000-mile-long trail, larger than the width of the continental U.S.

Learn more

Discover the full list of 10 things to know about our solar system this week HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Why Bennu?

Our OSIRIS-REx spacecraft will travel to a near-Earth asteroid, called Bennu, where it will collect a sample to bring back to Earth for study.

But why was Bennu chosen as the target destination asteroid for OSIRIS-REx? The science team took into account three criteria: accessibility, size and composition.

Accessibility: We need an asteroid that we can easily travel to, retrieve a sample from and return to Earth, all within a few years time. The closest asteroids are called near-Earth objects and they travel within 1.3 Astronomical Units (AU) of the sun. For those of you who don’t think in astronomical units…one Astronomical Unit is approximately equal to the distance between the sun and the Earth: ~93 million miles.

For a mission like OSIRIS-REx, the most accessible asteroids are somewhere between 0.08 – 1.6 AU. But we also needed to make sure that those asteroids have a similar orbit to Earth. Bennu fit this criteria! Check!

Size: We need an asteroid the right size to perform two critical portions of the mission: operations close to the asteroid and the actual sample collection from the surface of the asteroid. Bennu is roughly spherical and has a rotation period of 4.3 hours, which is in our size criteria. Check!

Composition: Asteroids are categorized by their spectral properties. In the visible and infrared light minerals have unique signatures or colors, much like fingerprints. Scientists use these fingerprints to identify molecules, like organics. For primitive, carbon-rich asteroids like Bennu, materials are preserved from over 4.5 billion years ago! We’re talking about the start of the formation of our solar system here! These primitive materials could contain organic molecules that may be the precursors to life here on Earth, or elsewhere in our solar system.

Thanks to telescopic observations in the visible and the infrared, as well as in radar, Bennu is currently the best understood asteroid not yet visited by a spacecraft.

All of these things make Bennu a fascinating and accessible asteroid for the OSIRIS-REx mission.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Starfish larvae, like other microorganisms, use tiny hair-like cilia to move the fluid around them. By beating these cilia in opposite directions on different parts of their bodies, the larvae create vortices, as seen in the flow visualization above. The starfish larvae don’t use these vortices for swimming – to swim, you’d want to push all the fluid in the same direction. Instead the vortices help the larvae feed. The more vortices they create, the more it stirs the fluid around them and draws in algae from far away. The larvae actually switch gears regularly, using few vortices when they want to swim and more when they want to eat. Check out the full video below to see the full explanation and more beautiful footage. (Image/video credit: W. Gilpin et al.)

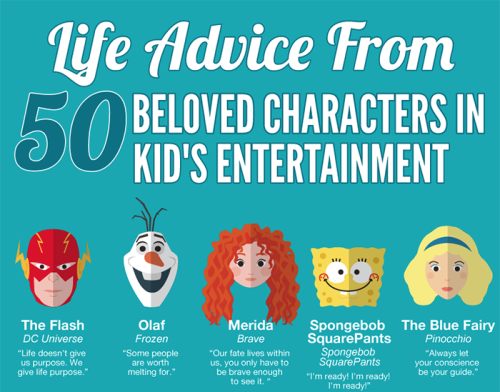

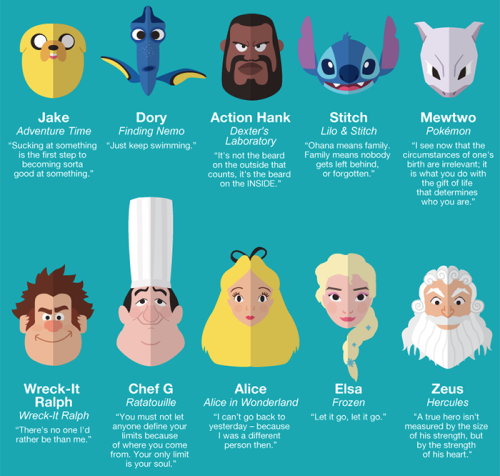

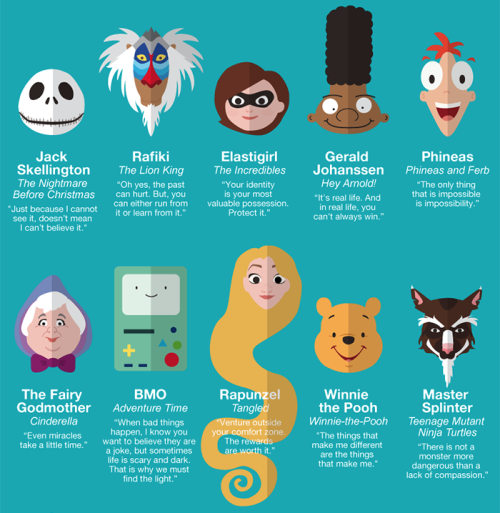

Life Advice from 50 Beloved Characters in Kid’s Entertainment by AAA State of Play -source-

The Van Allen Belt & the South Atlantic Anomaly

NASA’s first satellite, launched in 1958, discovered two giant swaths of radiation encircling Earth. Five decades later, scientists are still trying to unlock the mysteries of these phenomena known as the Van Allen belt. The belt is named after its discoverer, American astrophysicist James Van Allen.

The near-Earth space environment is a complex interaction between the planet’s magnetic field, cool plasma moving up from Earth’s ionosphere, and hotter plasma coming in from the solar wind. This dynamic region is populated by charged particles (electrons and ions) which occupy regions known as the plasmasphere and the Van Allen radiation belt. As solar wind and cosmic rays carry fast-moving, highly energized particles past Earth, some of these particles become trapped by the planet’s magnetic field. These particles carry a lot of energy, and it is important to mention their energies when describing the belt, because there are actually two distinct belts; one with energetic electrons forming the outer belt, and a combination of protons and electrons creating the inner belt. The resulting belts, can swell or shrink in size in response to incoming particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere and changes in the solar wind. Recent studies suggest that there is boundary at the inner edge of the outer belt at roughly 7,200 miles in altitude that appears to block the ultrafast electrons from breaching the invisible shield that protects Earth.

Earth’s magnetic field doesn’t exactly line up with the planet’s rotation axis, the belts are actually tilted a bit. Because of this asymmetry, one of the shields that trap potentially harmful particles from space dips down to 200 km (124 mi) altitude.

This dip in the earth’s magnetic field allows charged particles and cosmic rays to reach lower into the atmosphere. Satellites and other low orbiting spacecraft passing through this region of space actually enter the Van Allen radiation belt and are bombarded by protons. Exposure to such radiation can wreak havoc on satellite electronics, and pose serious health risks to astronauts. This peculiar region is called the South Atlantic Anomaly.

Credit: NASA/ESA/M. Kornmesser

-

happilylosti reblogged this · 1 month ago

happilylosti reblogged this · 1 month ago -

happilylosti liked this · 1 month ago

happilylosti liked this · 1 month ago -

paoloferrario1970 liked this · 6 months ago

paoloferrario1970 liked this · 6 months ago -

blueiscoool liked this · 8 months ago

blueiscoool liked this · 8 months ago -

avalon709 liked this · 11 months ago

avalon709 liked this · 11 months ago -

angel-viviz liked this · 11 months ago

angel-viviz liked this · 11 months ago -

kvtie-pie reblogged this · 1 year ago

kvtie-pie reblogged this · 1 year ago -

kvtie-pie liked this · 1 year ago

kvtie-pie liked this · 1 year ago -

monstalexa reblogged this · 1 year ago

monstalexa reblogged this · 1 year ago -

monstalexa liked this · 1 year ago

monstalexa liked this · 1 year ago -

the-raven-that-refused-to-sing reblogged this · 1 year ago

the-raven-that-refused-to-sing reblogged this · 1 year ago -

the-raven-that-refused-to-sing liked this · 1 year ago

the-raven-that-refused-to-sing liked this · 1 year ago -

epsilontauri reblogged this · 1 year ago

epsilontauri reblogged this · 1 year ago -

epsilontauri liked this · 1 year ago

epsilontauri liked this · 1 year ago -

norelorn reblogged this · 1 year ago

norelorn reblogged this · 1 year ago -

xploseof reblogged this · 1 year ago

xploseof reblogged this · 1 year ago -

devildog452 liked this · 1 year ago

devildog452 liked this · 1 year ago -

cerberus253 reblogged this · 1 year ago

cerberus253 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

big-boah liked this · 1 year ago

big-boah liked this · 1 year ago -

cowboycostume reblogged this · 1 year ago

cowboycostume reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mokuknight reblogged this · 1 year ago

mokuknight reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mokuknight liked this · 1 year ago

mokuknight liked this · 1 year ago -

bgyhbgyhbgyh liked this · 1 year ago

bgyhbgyhbgyh liked this · 1 year ago -

bgyhbgyhbgyh reblogged this · 1 year ago

bgyhbgyhbgyh reblogged this · 1 year ago -

dan-lee99 liked this · 1 year ago

dan-lee99 liked this · 1 year ago -

xanican-exile liked this · 1 year ago

xanican-exile liked this · 1 year ago -

keozai reblogged this · 1 year ago

keozai reblogged this · 1 year ago -

busterregalia liked this · 1 year ago

busterregalia liked this · 1 year ago -

aeilde-light reblogged this · 1 year ago

aeilde-light reblogged this · 1 year ago -

aeilde-light liked this · 1 year ago

aeilde-light liked this · 1 year ago -

cherrytartfilling liked this · 1 year ago

cherrytartfilling liked this · 1 year ago -

azzy-the-christian-furry reblogged this · 1 year ago

azzy-the-christian-furry reblogged this · 1 year ago -

azzy-the-christian-furry liked this · 1 year ago

azzy-the-christian-furry liked this · 1 year ago -

ysabelfaerie reblogged this · 1 year ago

ysabelfaerie reblogged this · 1 year ago -

ferngullyhedge reblogged this · 1 year ago

ferngullyhedge reblogged this · 1 year ago -

the-raven-that-refused-to-sing reblogged this · 1 year ago

the-raven-that-refused-to-sing reblogged this · 1 year ago -

toastedphantom liked this · 1 year ago

toastedphantom liked this · 1 year ago -

heatandapathy reblogged this · 1 year ago

heatandapathy reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heatandapathy liked this · 1 year ago

heatandapathy liked this · 1 year ago -

qualityblizzardcreation reblogged this · 1 year ago

qualityblizzardcreation reblogged this · 1 year ago -

magicalvin liked this · 1 year ago

magicalvin liked this · 1 year ago -

beardedmrbean reblogged this · 1 year ago

beardedmrbean reblogged this · 1 year ago -

schwarzebrandung liked this · 1 year ago

schwarzebrandung liked this · 1 year ago -

nordsturm reblogged this · 1 year ago

nordsturm reblogged this · 1 year ago -

anpaintsthemoon reblogged this · 1 year ago

anpaintsthemoon reblogged this · 1 year ago -

sensual-sideofme liked this · 1 year ago

sensual-sideofme liked this · 1 year ago