Solar System: Things To Know This Week

Solar System: Things to Know This Week

Learn the latest on Cassini’s Grand Finale, Pluto, Hubble Space Telescope and the Red Planet.

1. Cassini’s Grand Finale

After more than 12 years at Saturn, our Cassini mission has entered the final year of its epic voyage to the giant planet and its family of moons. But the journey isn’t over. The upcoming months will be like a whole new mission, with lots of new science and a truly thrilling ride in the unexplored space near the rings. Later this year, the spacecraft will fly repeatedly just outside the rings, capturing the closest views ever. Then, it will actually orbit inside the gap between the rings and the planet’s cloud tops.

Get details on Cassini’s final mission

The von Kármán Lecture Series: 2016

2. Chandra X-Rays Pluto

As the New Horizon’s mission headed to Pluto, our Chandra X-Ray Observatory made the first detection of the planet in X-rays. Chandra’s observations offer new insight into the space environment surrounding the largest and best-known object in the solar system’s outermost regions.

See Pluto’s X-Ray

3. … And Then Pluto Painted the Town Red

When the cameras on our approaching New Horizons spacecraft first spotted the large reddish polar region on Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, mission scientists knew two things: they’d never seen anything like it before, and they couldn’t wait to get the story behind it. After analyzing the images and other data that New Horizons has sent back from its July 2015 flight through the Pluto system, scientists think they’ve solved the mystery. Charon’s polar coloring comes from Pluto itself—as methane gas that escapes from Pluto’s atmosphere and becomes trapped by the moon’s gravity and freezes to the cold, icy surface at Charon’s pole.

Get the details

4. Pretty as a Postcard

The famed red-rock deserts of the American Southwest and recent images of Mars bear a striking similarity. New color images returned by our Curiosity Mars rover reveal the layered geologic past of the Red Planet in stunning detail.

More images

5. Things Fall Apart

Our Hubble Space Telescope recently observed a comet breaking apart. In a series of images taken over a three-day span in January 2016, Hubble captured images of 25 building-size blocks made of a mixture of ice and dust drifting away from the comet. The resulting debris is now scattered along a 3,000-mile-long trail, larger than the width of the continental U.S.

Learn more

Discover the full list of 10 things to know about our solar system this week HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

More Posts from Evisno and Others

A Glowing Pool Of Light

"NGC 3132 is a striking example of a planetary nebula. This expanding cloud of gas, surrounding a dying star, is known to amateur astronomers in the southern hemisphere as the "Eight-Burst" or the "Southern Ring" Nebula.

The name “planetary nebula” refers only to the round shape that many of these objects show when examined through a small visual telescope. In reality, these nebulae have little or nothing to do with planets, but are instead huge shells of gas ejected by stars as they near the ends of their lifetimes. NGC 3132 is nearly half a light year in diameter, and at a distance of about 2000 light years is one of the nearer known planetary nebulae. The gases are expanding away from the central star at a speed of 9 miles per second.

This image, captured by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, clearly shows two stars near the center of the nebula, a bright white one, and an adjacent, fainter companion to its upper right. (A third, unrelated star lies near the edge of the nebula.) The faint partner is actually the star that has ejected the nebula. This star is now smaller than our own Sun, but extremely hot. The flood of ultraviolet radiation from its surface makes the surrounding gases glow through fluorescence. The brighter star is in an earlier stage of stellar evolution, but in the future it will probably eject its own planetary nebula”

Credit: The Hubble Heritage Team

NASA’s WISE findings poke hole in black hole ‘doughnut’ theory

A survey of more than 170,000 supermassive black holes, using NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), has astronomers reexamining a decades-old theory about the varying appearances of these interstellar objects.

The unified theory of active, supermassive black holes, first developed in the late 1970s, was created to explain why black holes, though similar in nature, can look completely different. Some appear to be shrouded in dust, while others are exposed and easy to see.

The unified model answers this question by proposing that every black hole is surrounded by a dusty, doughnut-shaped structure called a torus. Depending on how these “doughnuts” are oriented in space, the black holes will take on various appearances. For example, if the doughnut is positioned so that we see it edge-on, the black hole is hidden from view. If the doughnut is observed from above or below, face-on, the black hole is clearly visible.

However, the new WISE results do not corroborate this theory. The researchers found evidence that something other than a doughnut structure may, in some circumstances, determine whether a black hole is visible or hidden. The team has not yet determined what this may be, but the results suggest the unified, or doughnut, model does not have all the answers.

Every galaxy has a massive black hole at its heart. The new study focuses on the “feeding” ones, called active, supermassive black holes, or active galactic nuclei. These black holes gorge on surrounding gas material that fuels their growth.

With the aid of computers, scientists were able to pick out more than 170,000 active supermassive black holes from the WISE data. They then measured the clustering of the galaxies containing both hidden and exposed black holes — the degree to which the objects clump together across the sky.

If the unified model was true, and the hidden black holes are simply blocked from view by doughnuts in the edge-on configuration, then researchers would expect them to cluster in the same way as the exposed ones. According to theory, since the doughnut structures would take on random orientations, the black holes should also be distributed randomly. It is like tossing a bunch of glazed doughnuts in the air — roughly the same percentage of doughnuts always will be positioned in the edge-on and face-on positions, regardless of whether they are tightly clumped or spread far apart.

But WISE found something totally unexpected. The results showed the galaxies with hidden black holes are more clumped together than those of the exposed black holes. If these findings are confirmed, scientists will have to adjust the unified model and come up with new ways to explain why some black holes appear hidden.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

I visited Nantes’ Natural History Museum.

All the times science fiction became fact

I don’t usually go for these really-big-ads-disguised-as-infographics (Really? Sci-fi ink & toner?), but this one was too cool to pass up.

Unfortunately, no hoverboards yet. But we’ve still got 15 months before time runs out on that one:

Bonus: Why are some science fiction authors so good at predicting the future? Check out this episode of It’s Okay To Be Smart where I talk all about that:

(via io9)

Polycephaly is the condition of having more than one head. Two-headed animals (called bicephalic or dicephalic) and three-headed (tricephalic) animals are the only type of multi-headed creatures seen in the real world, and form by the same process as conjoined twins from monozygotic twin embryos.

While two headed snakes are rare, they do occur in both the wild and in captivity at a rate of about 1 in 10,000 births. Most wild polycephalic snakes do not live long, but some captive individuals do. A two-headed black rat snake with separate throats and stomachs survived for 20 years.

(Sources: x x x x x x x x)

Drops of a liquid can often join a pool gradually through a process known as the coalescence cascade (top left). In this process, a drop sits atop a pool, separated by a thin air layer. Once that air drains out, contact is made and part of the drop coalesces. Then a smaller daughter droplet rebounds and the process repeats.

A recent study describes a related phenomenon (top right) in which the coalescence cascade is drastically sped up through the use of surfactants. The normal cascade depends strongly on the amount of time it takes for the air layer between the drop and pool to drain. By making the pool a liquid with a much greater surface tension value than the drop, the researchers sped up the air layer’s drainage. The mismatch in surface tension between the drop and pool creates an outward flow on the surface (below) due to the Marangoni effect. As the pool’s liquid moves outward, it drags air with it, thereby draining the separating layer more quickly. The result is still a coalescence cascade but one in which the later stages have no rebound and coalesce quickly. (Image and research credit: S. Shim and H. Stone, source)

Look Up! Perseid Meteor Shower Peaks Aug. 11-12

Asteroid Watch logo. Aug. 2, 2016 Make plans now to stay up late or set the alarm early next week to see a cosmic display of “shooting stars” light up the night sky. Known for it’s fast and bright meteors, the annual Perseid meteor shower is anticipated to be one of the best potential meteor viewing opportunities this year. The Perseids show up every year in August when Earth ventures through trails of debris left behind by an ancient comet. This year, Earth may be in for a closer encounter than usual with the comet trails that result in meteor shower, setting the stage for a spectacular display.

Image above: An outburst of Perseid meteors lights up the sky in August 2009 in this time-lapse image. Stargazers expect a similar outburst during next week’s Perseid meteor shower, which will be visible overnight on Aug. 11 and 12. Image Credits: NASA/JPL. “Forecasters are predicting a Perseid outburst this year with double normal rates on the night of Aug. 11-12,” said Bill Cooke with NASA’s Meteoroid Environments Office in Huntsville, Alabama. “Under perfect conditions, rates could soar to 200 meteors per hour.” An outburst is a meteor shower with more meteors than usual. The last Perseid outburst occurred in 2009. Every Perseid meteor is a tiny piece of the comet Swift-Tuttle, which orbits the sun every 133 years. Each swing through the inner solar system can leave trillions of small particles in its wake. When Earth crosses paths with Swift-Tuttle’s debris, specks of comet-stuff hit Earth’s atmosphere and disintegrate in flashes of light. These meteors are called Perseids because they seem to fly out of the constellation Perseus. Most years, Earth might graze the edge of Swift-Tuttle’s debris stream, where there’s less activity. Occasionally, though, Jupiter’s gravity tugs the huge network of dust trails closer, and Earth plows through closer to the middle, where there’s more material. This may be one of those years. Experts at NASA and elsewhere agree that three or more streams are on a collision course with Earth. “Here’s something to think about. The meteors you’ll see this year are from comet flybys that occurred hundreds if not thousands of years ago,” said Cooke. “And they’ve traveled billions of miles before their kamikaze run into Earth’s atmosphere.” How to Watch the Perseids The best way to see the Perseids is to go outside between midnight and dawn on the morning of Aug. 12. Allow about 45 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the dark. Lie on your back and look straight up. Increased activity may also be seen on Aug. 12-13. For stargazers experiencing cloudy or light-polluted skies, a live broadcast of the Perseid meteor shower will be available via Ustream overnight on Aug. 11-12 and Aug. 13-14, beginning at 10 p.m. EDT.: http://www.ustream.tv/channel/nasa-msfc

Meteor Moment: Viewing Tips.

More about the Perseids Perseid meteors travel at the blistering speed of 132,000 miles per hour (59 kilometers per second). That’s 500 times faster than the fastest car in the world. At that speed, even a smidgen of dust makes a vivid streak of light when it collides with Earth’s atmosphere. Peak temperatures can reach anywhere from 3,000 to 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit as they speed across the sky. The Perseids pose no danger to Earth. Most burn up 50 miles above our planet. But an outburst could mean trouble for spacecraft. About the Meteoroid Environment Office It’s Cooke’s job to help NASA understand and prepare for risks posed by meteoroids. He leads a team of meteor experts in the Meteoroid Environments Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. They study meteoroids in space so that NASA can protect our nation’s satellites, spacecraft and even astronauts aboard the International Space Station from these bits of tiny space debris. Related links: Meteors & Meteorites: http://www.nasa.gov/topics/solarsystem/features/watchtheskies/index.html Meteoroid Environments Office: https://www.nasa.gov/offices/meo/home/index.html Image (mentioned), Video, Text, Credits: NASA/Jennifer Harbaugh. Greetings, Orbiter.ch Full article

N44C nebula

On the middle left of the image is a source of its artistic likeness, a network of nebulous filaments surrounding the Wolf-Rayet star. This type of rare star is characterized by an exceptionally vigorous “wind” of charged particles. The shock of the wind colliding with the surrounding gas causes the gas to glow.

The Wolf-Rayet star is part of N44C, a nebula of glowing hydrogen gas surrounding young stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Visible from the Southern Hemisphere, the Large Magellanic Cloud is a small companion galaxy to the Milky Way.

What makes N44C peculiar is the temperature of the star that illuminates it. The most massive stars — those that are 10 to 50 times more massive than the Sun — have maximum temperatures of 30,000 to 50,000 degrees Celsius (54,000 to 90,000 degrees Fahrenheit). The temperature of this star is about 75,000 degrees Celsius (135,000 degrees Fahrenheit). This unusually high temperature may be due to a neutron star or black hole that occasionally produces X-rays but is now inactive.

N44C is part of a larger complex that includes young, hot, massive stars, nebulae, and a “superbubble” blown out by multiple supernova explosions. Part of the superbubble is seen in red at the very bottom left of the Hubble image.

Credit: NASA/JPL/Hubble

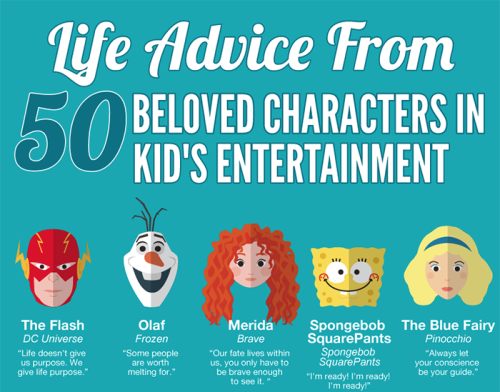

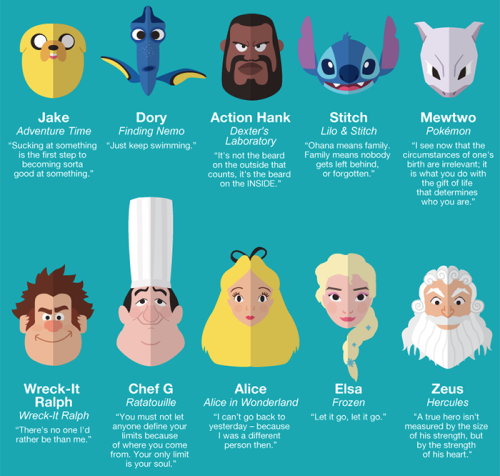

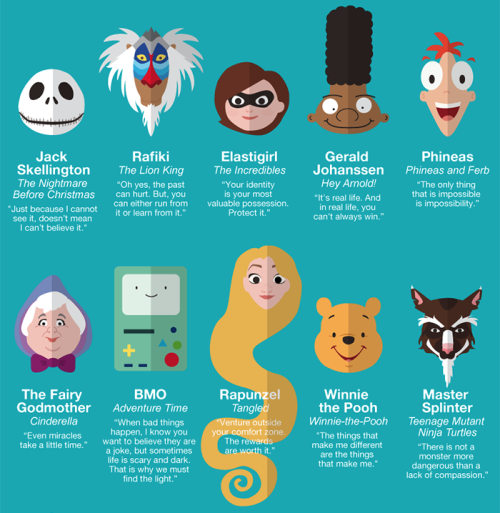

Life Advice from 50 Beloved Characters in Kid’s Entertainment by AAA State of Play -source-

How Do Volcanoes Make Lightning?

“Volcanic lightning appears to occur most frequently around volcanoes with large ash plumes, particularly during active stages of the eruption, where flowing, molten lava creates the largest temperature gradients. The phenomena of lightning has been exquisitely recorded around a number of recent volcanic eruptions, including Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull, Japan’s Sakurajima, Italy’s Mt. Etna, and Chile’s Puyehue, Calbuco and Chaiten volcanoes. But what you may not know is this phenomenon was not only captured during Mt. Vesuvius’ last eruption in 1944, but was accurately described nearly 2,000 years ago when it erupted all the way back in the year 79!”

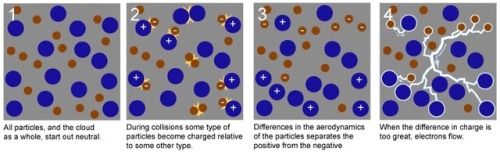

Volcanoes are some of the most potentially destructive natural phenomena known to occur on our world. The most violent eruptions feature not only lava, but soot, ash, volatile gases, and even enormous chunks of rock hurled great distances. What you might not realize, however, is just how frequently these eruptions are accompanied by another spectacular show: volcanic lightning. Lightning isn’t only found in thunderstorms or other great electrical discharges between the clouds and the ground, but is produced in volcanic eruptions all throughout the world, and throughout history as well. After countless generations, where we wondered what could produce such an unusual but spectacular show, we’ve finally figured it out.

Come get the science behind how volcanoes make lightning, and enjoy some of the greatest photographs of this phenomena humanity’s ever taken!

-

katty2088 liked this · 2 years ago

katty2088 liked this · 2 years ago -

vanessa-spice-runner reblogged this · 4 years ago

vanessa-spice-runner reblogged this · 4 years ago -

tulinkiper reblogged this · 4 years ago

tulinkiper reblogged this · 4 years ago -

vordorvitriol reblogged this · 6 years ago

vordorvitriol reblogged this · 6 years ago -

kyu7000-blog liked this · 7 years ago

kyu7000-blog liked this · 7 years ago -

art-hoe-2000 liked this · 7 years ago

art-hoe-2000 liked this · 7 years ago -

alex-webster liked this · 7 years ago

alex-webster liked this · 7 years ago -

cubanaj1-blog liked this · 7 years ago

cubanaj1-blog liked this · 7 years ago -

cookiemarimonster liked this · 8 years ago

cookiemarimonster liked this · 8 years ago -

best-hotels-posts reblogged this · 8 years ago

best-hotels-posts reblogged this · 8 years ago -

joellehelou8-blog liked this · 8 years ago

joellehelou8-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

greybeard55 reblogged this · 8 years ago

greybeard55 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

greybeard55 liked this · 8 years ago

greybeard55 liked this · 8 years ago -

cosmicripple reblogged this · 8 years ago

cosmicripple reblogged this · 8 years ago -

amabilis liked this · 8 years ago

amabilis liked this · 8 years ago -

denissegnz liked this · 8 years ago

denissegnz liked this · 8 years ago -

xjii liked this · 8 years ago

xjii liked this · 8 years ago -

polivien1-blog liked this · 8 years ago

polivien1-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

mcm-curiosity liked this · 8 years ago

mcm-curiosity liked this · 8 years ago -

oniwoolf-blog liked this · 8 years ago

oniwoolf-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

set-saiil liked this · 8 years ago

set-saiil liked this · 8 years ago -

ackwok reblogged this · 8 years ago

ackwok reblogged this · 8 years ago -

artsdrawingsandgamesold-blog liked this · 8 years ago

artsdrawingsandgamesold-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

bertoltblecht liked this · 8 years ago

bertoltblecht liked this · 8 years ago -

o-sacra-virgo-laudes-tibi reblogged this · 8 years ago

o-sacra-virgo-laudes-tibi reblogged this · 8 years ago