Neuroscientist Captures An MRI Of A Mother And Child

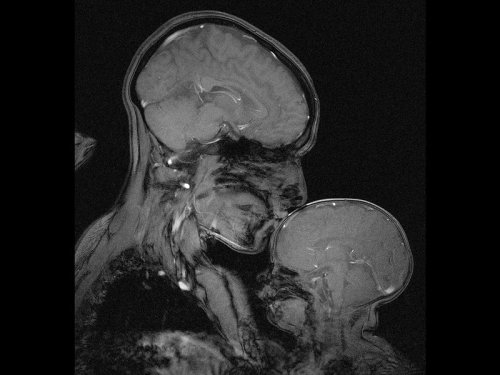

Neuroscientist captures an MRI of a mother and child

Professor Rebecca Saxe (MIT) has taken the first ever MR image of a mother and child.

“This picture is an MR image of a mother and a child that I made in my lab at MIT. You might see it as sweet and touching… an image of universal love. We can’t see clothes or hairstyles or even skin colour. From what we do see, the biology and the brains, this could be any mother and child or even father and child at any time and place in history; having an experience that any human can recognise.

Or you might see it as disturbing, a reminder that our human bodies are much too fragile as houses for ourselves. MRI’s are usually medical images and often bad news. Each white spot in that picture is a blood vessel that could clog, each tiny fold of those brains could harbour a tumour. The baby’s brain maybe looks particularly vulnerable pressed against the soft thin shell of its skull.

I see those things, universal emotions and frightening fragility but I also see one of the most amazing transformations in biology.”

Quotes have been taken from a TEDx talk given by Professor Saxe explaining the story behind the above picture.

More Posts from Contradictiontonature and Others

Steve Gentleman, a neuropathologist, demonstrates the process of brain dissection and preservation for research.

At last, we’ve seen what might be the primary building blocks of memories lighting up in the brains of mice.

We have cells in our brains – and so do rodents – that keep track of our location and the distances we’ve travelled. These neurons are also known to fire in sequence when a rat is resting, as if the animal is mentally retracing its path – a process that probably helps memories form, says Rosa Cossart at the Institut de Neurobiologie de la Méditerranée in Marseille, France.

But without a way of mapping the activity of a large number of these individual neurons, the pattern that these replaying neurons form in the brain has been unclear. Researchers have suspected for decades that the cells might fire together in small groups, but nobody could really look at them, says Cossart.

To get a look, Cossart and her team added a fluorescent protein to the neurons of four mice. This protein fluoresces the most when calcium ions flood into a cell – a sign that a neuron is actively firing. The team used this fluorescence to map neuron activity much more widely than previous techniques, using implanted electrodes, have been able to do.

Observing the activity of more than 1000 neurons per mouse, the team watched what happened when mice walked on a treadmill or stood still.

As expected, when the mice were running, the neurons that trace how far the animal has travelled fired in a sequential pattern, keeping track.

These same cells also lit up while the mice were resting, but in a strange pattern. As they reflected on their memories, the neurons fired in the same sequence as they had when the animals were running, but much faster. And rather than firing in turn individually, they fired together in sequential blocks that corresponded to particular fragments of a mouse’s run.

“We’ve been able to image the individual building-blocks of memory,” Cossart says, each one reflecting a chunk of the original episode that the mouse experienced.

Continue Reading.

Liver Circulation - Flashcard

The liver is supplied with blood by the hepatic artery and the hepatic portal vein

branches of the hepatic artery and the hepatic portal vein distribute blood to the periphery of the liver lobules.

Blood passes along sinusoids, which are lined by hepatocytes, which perform numerous metabolic and synthetic functions.

The processed blood passes into branches of the hepatic vein in the centre of each lobule, and eventually drains into the hepatic vein.

The biliary system is independent of the vascular system and bile moves in the opposite direction to the blood.

Initially it is collected in bile ductules which are surrounded by collagenous tissue, which forms part of the collagenous trabecular septum.

The bile is collected by increasingly large trabecular ducts, which fuse to form intrahepatic ducts which finally drain into the main hepatic ducts.

Rosalind Franklin was born #OTD in 1920. Her work was instrumental in the discovery of the structure of DNA: http://wp.me/s4aPLT-franklin

Archbishop Ussher’s chronology was taken as gospel in the Western world. Until we turned to another book to find the age of the earth, the one that was written in the rocks themselves.

COLORS OF CHEMISTRY

The bright colors of chemistry fascinate people of all ages. Hriday Bhattacharjee, a Ph.D. student in the lab of Jens Mueller at the University of Saskatchewan, assembled this showcase from compounds he prepared as well as from some synthesized by the undergraduate students he teaches. Organometallic and inorganic chemistry—the study of molecules like these that involve metal atoms—is especially colorful.

The table below the picture indicates the chemicals seen in the photo.

Submitted by Hriday Bhattacharjee

Do science. Take pictures. Win money: Enter our photo contest.

Fungal tissues – the fungal mantle around the root tip and the fungal network of tendrils that penetrates the root of plants, or Hartig Net, between Pinus sylvestris plant root cells – in green. Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi help trees tolerate drought and boost the productivity of bioenergy feedstock trees, including poplar and willow.

Via Berkeley Lab: The sclerotia are in the soil!

More: How Fungi Help Trees Tolerate Drought (Joint Genome Institute)

Social Stress Leads To Changes In Gut Bacteria

Exposure to psychological stress in the form of social conflict alters gut bacteria in Syrian hamsters, according to a new study by Georgia State University.

It has long been said that humans have “gut feelings” about things, but how the gut might communicate those “feelings” to the brain was not known. It has been shown that gut microbiota, the complex community of microorganisms that live in the digestive tracts of humans and other animals, can send signals to the brain and vice versa.

In addition, recent data have indicated that stress can alter the gut microbiota. The most common stress experienced by humans and other animals is social stress, and this stress can trigger or worsen mental illness in humans. Researchers at Georgia State have examined whether mild social stress alters the gut microbiota in Syrian hamsters, and if so, whether this response is different in animals that “win” compared to those that “lose” in conflict situations.

Hamsters are ideal to study social stress because they rapidly form dominance hierarchies when paired with other animals. In this study, pairs of adult males were placed together and they quickly began to compete, resulting in dominant (winner) and subordinate (loser) animals that maintained this status throughout the experiment. Their gut microbes were sampled before and after the first encounter as well as after nine interactions. Sampling was also done in a control group of hamsters that were never paired and thus had no social stress. The researchers’ findings are published in the journal Behavioural Brain Research.

“We found that even a single exposure to social stress causes a change in the gut microbiota, similar to what is seen following other, much more severe physical stressors, and this change gets bigger following repeated exposures,” said Dr. Kim Huhman, Distinguished University Professor of Neuroscience at Georgia State. “Because ‘losers’ show much more stress hormone release than do ‘winners,’ we initially hypothesized that the microbial changes would be more pronounced in animals that lost than in animals that won.”

“Interestingly, we found that social stress, regardless of who won, led to similar overall changes in the microbiota, although the particular bacteria that were impacted were somewhat different in winners and losers. It might be that the impact of social stress was somewhat greater for the subordinate animals, but we can’t say that strongly.”

Another unique finding came from samples that were taken before the animals were ever paired, which were used to determine if any of the preexisting bacteria seemed to correlate with whether an animal turned out to be the winner or loser.

“It’s an intriguing finding that there were some bacteria that seemed to predict whether an animal would become a winner or a loser,” Huhman said.

“These findings suggest that bi-directional communication is occurring, with stress impacting the microbiota, and on the other hand, with some specific bacteria in turn impacting the response to stress,” said Dr. Benoit Chassaing, assistant professor in the Neuroscience Institute at Georgia State.

This is an exciting possibility that builds on evidence that gut microbiota can regulate social behavior and is being investigated by Huhman and Chassaing.

Antibiotic resistance has been called one of the biggest public health threats of our time. There is a pressing need for new and novel antibiotics to combat the rise in antibiotic-resistant bacteria worldwide.

Researchers from Florida International University’s Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine are part of an international team that has discovered a new broad-spectrum antibiotic that contains arsenic. The study, published in Nature’s Communication Biology, is a collaboration between Barry P. Rosen, Masafumi Yoshinaga, Venkadesh Sarkarai Nadar and others from the Department of Cellular Biology and Pharmacology, and Satoru Ishikawa and Masato Kuramata from the Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, NARO in Japan.

“The antibiotic, arsinothricin or AST, is a natural product made by soil bacteria and is effective against many types of bacteria, which is what broad-spectrum means,” said Rosen, co-senior author of the study published in the Nature journal, Communications Biology. “Arsinothricin is the first and only known natural arsenic-containing antibiotic, and we have great hopes for it.”

Although it contains arsenic, researchers say they tested AST toxicity on human blood cells and reported that “it doesn’t kill human cells in tissue culture.”

Continue Reading.

This illustrator’s new book is a clever introduction to women scientists through history.

During a dinnertime discussion two years ago, illustrator Rachel Ignotofsky and her friend started chewing on the subject of what’s become a meaty conversation in America: women’s representation in STEM fields.

Ignotofsky, who lives in Kansas City, Missouri, lamented that kids don’t seem to hear much about women scientists. “I just kept saying over and over and over again that we’re not taught the stories of these women when we’re in school,” she recalls. Eventually, it dawned on her: “I was saying it enough that I was like, you know, I’m just talking a lot about this; I should draw some of the women in science that I feel really excited about.”

Learn more here.

[Reprinted with permission from Women in Science Copyright ©2016 by Rachel Ignotofsky. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.]

-

tea-tties liked this · 4 years ago

tea-tties liked this · 4 years ago -

neslepaks liked this · 4 years ago

neslepaks liked this · 4 years ago -

mfreedomstuff liked this · 5 years ago

mfreedomstuff liked this · 5 years ago -

artificialcherryflavour liked this · 5 years ago

artificialcherryflavour liked this · 5 years ago -

archeia99 reblogged this · 5 years ago

archeia99 reblogged this · 5 years ago -

archeia99 liked this · 5 years ago

archeia99 liked this · 5 years ago -

artificialcherryflavour reblogged this · 6 years ago

artificialcherryflavour reblogged this · 6 years ago -

sarahlorett liked this · 6 years ago

sarahlorett liked this · 6 years ago -

190624 reblogged this · 6 years ago

190624 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

are-you-a-watcher-or-player liked this · 6 years ago

are-you-a-watcher-or-player liked this · 6 years ago -

luluuu02-blog liked this · 6 years ago

luluuu02-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

noodlesandcake reblogged this · 7 years ago

noodlesandcake reblogged this · 7 years ago -

tmedic reblogged this · 7 years ago

tmedic reblogged this · 7 years ago -

jouncensored-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago

jouncensored-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago -

jouncensored-blog liked this · 7 years ago

jouncensored-blog liked this · 7 years ago -

boobooluvzu liked this · 7 years ago

boobooluvzu liked this · 7 years ago -

flawedhue liked this · 7 years ago

flawedhue liked this · 7 years ago -

f0rthew0rds liked this · 7 years ago

f0rthew0rds liked this · 7 years ago -

gothauntclaudia liked this · 7 years ago

gothauntclaudia liked this · 7 years ago -

darthlenaplant liked this · 7 years ago

darthlenaplant liked this · 7 years ago -

fashionratsz liked this · 7 years ago

fashionratsz liked this · 7 years ago -

bachatanero liked this · 7 years ago

bachatanero liked this · 7 years ago -

pepin-the-short liked this · 7 years ago

pepin-the-short liked this · 7 years ago -

samashithtong-blog liked this · 7 years ago

samashithtong-blog liked this · 7 years ago -

juliesosa reblogged this · 7 years ago

juliesosa reblogged this · 7 years ago -

juliesosa liked this · 7 years ago

juliesosa liked this · 7 years ago -

asocialacademic liked this · 7 years ago

asocialacademic liked this · 7 years ago -

ilseannchavez liked this · 8 years ago

ilseannchavez liked this · 8 years ago -

complexmed-blog liked this · 8 years ago

complexmed-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

lasoupedujourestlight reblogged this · 8 years ago

lasoupedujourestlight reblogged this · 8 years ago -

heythatsprettyneit liked this · 8 years ago

heythatsprettyneit liked this · 8 years ago -

diveniredreams liked this · 8 years ago

diveniredreams liked this · 8 years ago -

aaaaanaaaaaa liked this · 8 years ago

aaaaanaaaaaa liked this · 8 years ago -

sunorpiycema liked this · 8 years ago

sunorpiycema liked this · 8 years ago -

jiminghoul liked this · 8 years ago

jiminghoul liked this · 8 years ago -

cypress-sequoia liked this · 8 years ago

cypress-sequoia liked this · 8 years ago -

qveen-of-procrastination liked this · 8 years ago

qveen-of-procrastination liked this · 8 years ago -

zh1608 liked this · 8 years ago

zh1608 liked this · 8 years ago -

mega-super-batman reblogged this · 8 years ago

mega-super-batman reblogged this · 8 years ago -

mega-super-batman liked this · 8 years ago

mega-super-batman liked this · 8 years ago -

studyingslob reblogged this · 8 years ago

studyingslob reblogged this · 8 years ago -

heartbeatstudies reblogged this · 8 years ago

heartbeatstudies reblogged this · 8 years ago

A pharmacist and a little science sideblog. "Knowledge belongs to humanity, and is the torch which illuminates the world." - Louis Pasteur

215 posts