Europa

Europa

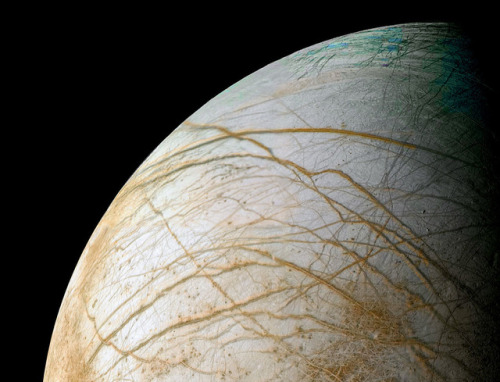

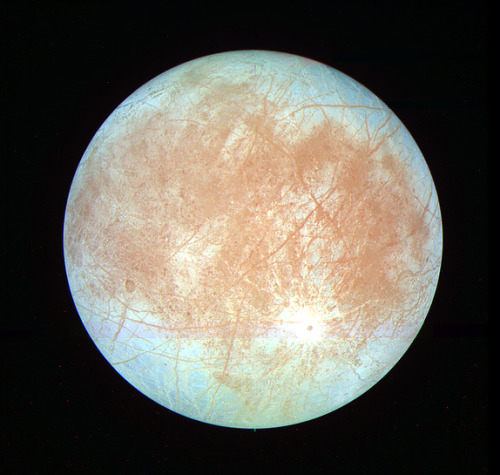

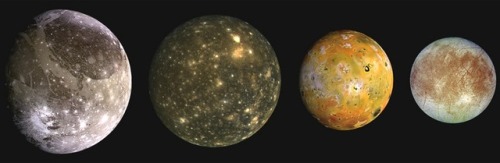

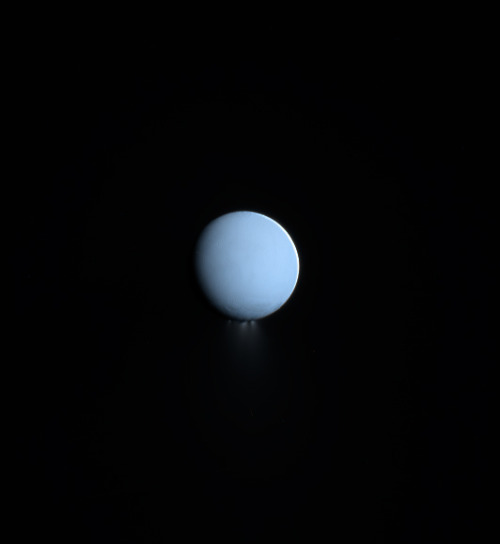

Jupiter’s moon Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s moon. Its surface is smooth and bright, consisting of water ice crisscrossed by long, linear fractures. Like our planet, Europa is thought to have an iron core, a rocky mantle and an ocean of salty water beneath its ice crust. Unlike Earth, however, this ocean would be deep enough to extend from the moon’s surface to the top of its rocky mantle. Being far from the sun, the ocean’s surface would be globally frozen over. While evidence for this internal ocean is quite strong, its presence awaits confirmation by a future mission.

Europa orbits Jupiter every 3.5 days and is locked by gravity to Jupiter such that the same hemisphere of the moon always faces the planet. Because Europa’s orbit is slightly stretched out from circular, or elliptical, its distance from Jupiter varies, creating tides that stretch and relax its surface. The tides occur because Jupiter’s gravity is just slightly stronger on the near side of the moon than on the far side, and the magnitude of this difference changes as Europa orbits. Flexing from the tides supplies energy to the moon’s icy shell, creating the linear fractures across its surface. If Europa’s ocean exists, the tides might also create volcanic or hydrothermal activity on the seafloor, supplying nutrients that could make the ocean suitable for living things.

Europa Clipper

NASA’s planned Europa Clipper would conduct detailed reconnaissance of Jupiter’s moon Europa and investigate whether the icy moon could harbor conditions suitable for life.

The mission would place a spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter in order to perform a detailed investigation of the giant planet’s moon Europa – a world that shows strong evidence for an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust and which could host conditions favorable for life. The mission would send a highly capable, radiation-tolerant spacecraft into a long, looping orbit around Jupiter to perform repeated close flybys of Europa. NASA has selected nine science instruments for a future mission to Europa. The selected payload includes cameras and spectrometers to produce high-resolution images of Europa’s surface and determine its composition. An ice penetrating radar would determine the thickness of the moon’s icy shell and search for subsurface lakes similar to those beneath Antarctica’s ice sheet. The mission would also carry a magnetometer to measure the strength and direction of the moon’s magnetic field, which would allow scientists to determine the depth and salinity of its ocean.

Image credit: NASA / JPL / Galileo / Voyager & Processed by Kevin M. Gill

Credit: NASA & Europa Clipper Mission

More Posts from Xyhor-astronomy and Others

Space Station flight from a clear North Africa over a story Mediterranean

Apollo 11 Launch

A slow-motion animation of the Crab Pulsar taken at 800 nm wavelength (near-infrared) using a Lucky Imaging camera from Cambridge University, showing the bright pulse and fainter interpulse.

Credit: Cambridge University Lucky Imaging Group

December 13, 1972 – Photos taken during the Apollo 17 rover’s drive back to the lunar module. (NASA)

North Cascades National Park, Washington

A night in the Cascade Mountains

Comet Lovejoy is visible near Earth’s horizon in this nighttime image photographed by NASA astronaut Dan Burbank, Expedition 30 commander, onboard the International Space Station on Dec. 21, 2011.

Image credit: NASA

A Hitchhiker’s Ride to Space

This month, we are set to launch the latest weather satellite from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Joint Polar Satellite System-1, or JPSS-1, satellite will provide essential data for timely and accurate weather forecasts and for tracking environmental events such as forest fires and droughts.

Image Credit: Ball Aerospace

JPSS-1 is the primary satellite launching, but four tiny satellites will also be hitchhiking a ride into Earth orbit. These shoebox-sized satellites (part of our CubeSat Launch Initiative) were developed in partnership with university students and used for education, research and development. Here are 4 reasons why MiRaTA, one of the hitchhikers, is particularly interesting…

Miniaturized Weather Satellite Technology

The Microwave Radiometer Technology Acceleration (MiRaTA) CubeSat is set to orbit the Earth to prove that a small satellite can advance the technology necessary to reduce the cost and size of future weather satellites. At less than 10 pounds, these nanosatellites are faster and more cost-effective to build and launch since they have been constructed by Principal Investigator Kerri Cahoy’s students at MIT Lincoln Laboratory (with lots of help). There’s even a chance it could be put into operation with forecasters.

The Antenna? It’s a Measuring Tape

That long skinny piece coming out of the bottom right side under MiRaTA’s solar panel? That’s a measuring tape. It’s doubling as a communications antenna. MiRaTA will measure temperature, water vapor and cloud ice in Earth’s atmosphere. These measurements are used to track major storms, including hurricanes, as well as everyday weather. If this test flight is successful, the new, smaller technology will likely be incorporated into future weather satellites – part of our national infrastructure.

Tiny Package Packing a Punch MiRaTA will also test a new technique using radio signals received from GPS satellites in a higher orbit. They will be used to measure the temperature of the same volume of atmosphere that the radiometer is viewing. The GPS satellite measurement can then be used for calibrating the radiometer. “In physics class, you learn that a pencil submerged in water looks like it’s broken in half because light bends differently in the water than in the air,” Principal Investigator Kerri Cahoy said. “Radio waves are like light in that they refract when they go through changing densities of air, and we can use the magnitude of the refraction to calculate the temperature of the surrounding atmosphere with near-perfect accuracy and use this to calibrate a radiometer.”

What’s Next?

In the best-case scenario, three weeks after launch MiRaTA will be fully operational, and within three months the team will have obtained enough data to study if this technology concept is working. The big goal for the mission—declaring the technology demonstration a success—would be confirmed a bit farther down the road, at least half a year away, following the data analysis. If MiRaTA’s technology validation is successful, Cahoy said she envisions an eventual constellation of these CubeSats orbiting the entire Earth, taking snapshots of the atmosphere and weather every 15 minutes—frequent enough to track storms, from blizzards to hurricanes, in real time.

Learn more about MiRaTA

Watch the launch!

The mission is scheduled to launch this month (no sooner than Nov. 14), with JPSS-1 atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Delta II rocket lifting off from Space Launch Complex 2 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. You’ll be able to watch on NASA TV or at nasa.gov/live.

Watch the launch live HERE on Nov. 14, liftoff is scheduled for Tuesday, 4:47 a.m.!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

If we ever want a long-distance relationship with aliens, they have to be able to find us.

NASAs Solar Dynamics Observatory captured this image of a significant solar flare as seen in the bright flash on the right on Dec. 19, 2014. The image shows a subset of extreme ultraviolet light that highlights the extremely hot material in flares

js

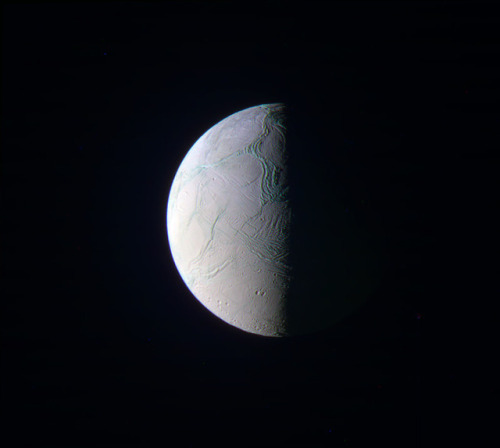

Enceladus

Enceladus is one of the major inner moons of Saturn along with Dione, Tethys, and Mimas. It orbits Saturn at a distance of 148,000 miles (238,000 km), falling between the orbits of Mimas and Tethys. It is tidally locked with Saturn, keeping the same face toward the planet. It completes one orbit every 32.9 hours within the densest part of Saturn’s E Ring, the outermost of its major rings, and is its main source.

Enceladus is, like many moons in the extensive systems of the giant planets, trapped in an orbital resonance. Its resonance with Dione excites its orbital eccentricity, which is damped by tidal forces, tidally heating its interior, and possibly driving the geological activity.

Enceladus is Saturn’s sixth largest moon, only 157 miles (252 km) in mean radius, but it’s one of the most scientifically compelling bodies in our solar system. Hydrothermal vents spew water vapor and ice particles from an underground ocean beneath the icy crust of Enceladus. This plume of material includes organic compounds, volatile gases, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, salts and silica.

With its global ocean, unique chemistry and internal heat, Enceladus has become a promising lead in our search for worlds where life could exist.

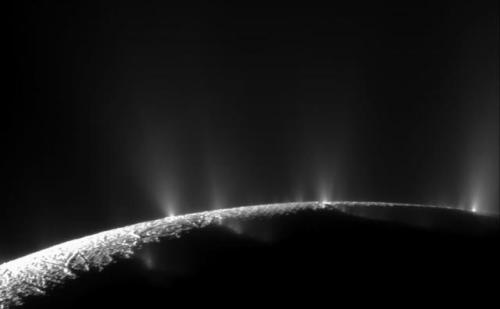

In 2005, Cassini’s multiple instruments discovered that this icy outpost is gushing water vapor geysers out to a distance of three times the radius of Enceladus. The icy water particles are roughly one ten-thousandth of an inch, or about the width of a human hair. The particles and gas escape the surface at jet speed at approximately 800 miles per hour (400 meters per second). The eruptions appear to be continuous, refreshing the surface and generating an enormous halo of fine ice dust around Enceladus, which supplies material to one of Saturn’s rings, the E-ring.

Several gases, including water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, perhaps a little ammonia and either carbon monoxide or nitrogen gas make up the gaseous envelope of the plume.

Read more at: solarsystem.nasa.gov

Image credit: NASA/JPL/Cassini & Kevin Gill

-

littlepuffy4ever liked this · 2 months ago

littlepuffy4ever liked this · 2 months ago -

bonusforbonzo liked this · 1 year ago

bonusforbonzo liked this · 1 year ago -

hasuppnapefer liked this · 1 year ago

hasuppnapefer liked this · 1 year ago -

fallinoutoforbit liked this · 1 year ago

fallinoutoforbit liked this · 1 year ago -

s0cr4t3s reblogged this · 1 year ago

s0cr4t3s reblogged this · 1 year ago -

s0cr4t3s liked this · 1 year ago

s0cr4t3s liked this · 1 year ago -

echecrates liked this · 2 years ago

echecrates liked this · 2 years ago -

wonders-of-the-cosmos liked this · 2 years ago

wonders-of-the-cosmos liked this · 2 years ago -

dreaming-moon-child reblogged this · 2 years ago

dreaming-moon-child reblogged this · 2 years ago -

hgfcdj liked this · 2 years ago

hgfcdj liked this · 2 years ago -

losusdesperatus liked this · 2 years ago

losusdesperatus liked this · 2 years ago -

00101001lilill00101001 liked this · 2 years ago

00101001lilill00101001 liked this · 2 years ago -

nahdogyouarenthavingit liked this · 2 years ago

nahdogyouarenthavingit liked this · 2 years ago -

werewolf240moon liked this · 2 years ago

werewolf240moon liked this · 2 years ago -

themardlonk reblogged this · 2 years ago

themardlonk reblogged this · 2 years ago -

daskrug reblogged this · 3 years ago

daskrug reblogged this · 3 years ago -

hyggev liked this · 3 years ago

hyggev liked this · 3 years ago -

lokaarc liked this · 3 years ago

lokaarc liked this · 3 years ago -

robbiedaus40 reblogged this · 4 years ago

robbiedaus40 reblogged this · 4 years ago -

robbiedaus40 liked this · 4 years ago

robbiedaus40 liked this · 4 years ago -

etherunreal reblogged this · 4 years ago

etherunreal reblogged this · 4 years ago -

moon-waterrr liked this · 4 years ago

moon-waterrr liked this · 4 years ago -

synchlora liked this · 4 years ago

synchlora liked this · 4 years ago -

witherhoard-enthusiast reblogged this · 4 years ago

witherhoard-enthusiast reblogged this · 4 years ago -

witherhoard-enthusiast liked this · 4 years ago

witherhoard-enthusiast liked this · 4 years ago -

capt-aldair liked this · 4 years ago

capt-aldair liked this · 4 years ago -

confusedcataclysm reblogged this · 4 years ago

confusedcataclysm reblogged this · 4 years ago -

confusedcataclysm liked this · 4 years ago

confusedcataclysm liked this · 4 years ago

For more content, Click Here and experience this XYHor in its entirety!Space...the Final Frontier. Let's boldly go where few have gone before with XYHor: Space: Astronomy & Spacefaring: the collection of the latest finds and science behind exploring our solar system, how we'll get there and what we need to be prepared for!

128 posts