Microscopic Cars Square Off In Big Race

This car race involved years of training, feats of engineering, high-profile sponsorships, competitors from around the world and a racetrack made of gold.

But the high-octane competition, described as a cross between physics and motor-sports, is invisible to the naked eye. In fact, the track itself is only a fraction of the width of a human hair, and the cars themselves are each comprised of a single molecule.

The Nanocar Race, which happened over the weekend at Le centre national de la recherché scientific in Toulouse, France, was billed as the “first-ever race of molecule-cars.”

It’s meant to generate excitement about molecular machines. Research on the tiny structures won last year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry, and they have been lauded as the “first steps into a new world,” as The Two-Way reported.

Microscopic Cars Square Off In Big Race

Image: CNRS

More Posts from Smparticle2 and Others

Balancing Time and Space in the Brain: A New Model Holds Promise for Predicting Brain Dynamics

For as long as scientists have been listening in on the activity of the brain, they have been trying to understand the source of its noisy, apparently random, activity. In the past 20 years, “balanced network theory” has emerged to explain this apparent randomness through a balance of excitation and inhibition in recurrently coupled networks of neurons. A team of scientists has extended the balanced model to provide deep and testable predictions linking brain circuits to brain activity.

Lead investigators at the University of Pittsburgh say the new model accurately explains experimental findings about the highly variable responses of neurons in the brains of living animals. On Oct. 31, their paper, “The spatial structure of correlated neuronal variability,” was published online by the journal Nature Neuroscience.

The new model provides a much richer understanding of how activity is coordinated between neurons in neural circuits. The model could be used in the future to discover neural “signatures” that predict brain activity associated with learning or disease, say the investigators.

“Normally, brain activity appears highly random and variable most of the time, which looks like a weird way to compute,” said Brent Doiron, associate professor of mathematics at Pitt, senior author on the paper, and a member of the University of Pittsburgh Brain Institute (UPBI). “To understand the mechanics of neural computation, you need to know how the dynamics of a neuronal network depends on the network’s architecture, and this latest research brings us significantly closer to achieving this goal.”

Earlier versions of the balanced network theory captured how the timing and frequency of inputs—excitatory and inhibitory—shaped the emergence of variability in neural behavior, but these models used shortcuts that were biologically unrealistic, according to Doiron.

“The original balanced model ignored the spatial dependence of wiring in the brain, but it has long been known that neuron pairs that are near one another have a higher likelihood of connecting than pairs that are separated by larger distances. Earlier models produced unrealistic behavior—either completely random activity that was unlike the brain or completely synchronized neural behavior, such as you would see in a deep seizure. You could produce nothing in between.”

In the context of this balance, neurons are in a constant state of tension. According to co-author Matthew Smith, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Pitt and a member of UPBI, “It’s like balancing on one foot on your toes. If there are small overcorrections, the result is big fluctuations in neural firing, or communication.”

The new model accounts for temporal and spatial characteristics of neural networks and the correlations in the activity between neurons—whether firing in one neuron is correlated with firing in another. The model is such a substantial improvement that the scientists could use it to predict the behavior of living neurons examined in the area of the brain that processes the visual world.

After developing the model, the scientists examined data from the living visual cortex and found that their model accurately predicted the behavior of neurons based on how far apart they were. The activity of nearby neuron pairs was strongly correlated. At an intermediate distance, pairs of neurons were anticorrelated (When one responded more, the other responded less.), and at greater distances still they were independent.

“This model will help us to better understand how the brain computes information because it’s a big step forward in describing how network structure determines network variability,” said Doiron. “Any serious theory of brain computation must take into account the noise in the code. A shift in neuronal variability accompanies important cognitive functions, such as attention and learning, as well as being a signature of devastating pathologies like Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy.”

While the scientists examined the visual cortex, they believe their model could be used to predict activity in other parts of the brain, such as areas that process auditory or olfactory cues, for example. And they believe that the model generalizes to the brains of all mammals. In fact, the team found that a neural signature predicted by their model appeared in the visual cortex of living mice studied by another team of investigators.

“A hallmark of the computational approach that Doiron and Smith are taking is that its goal is to infer general principles of brain function that can be broadly applied to many scenarios. Remarkably, we still don’t have things like the laws of gravity for understanding the brain, but this is an important step for providing good theories in neuroscience that will allow us to make sense of the explosion of new experimental data that can now be collected,” said Nathan Urban, associate director of UPBI.

Why can we find geometric shapes in the night sky? How can we know that at least two people in London have exactly the same number of hairs on their head? And why can patterns be found in just about any text — even Vanilla Ice lyrics? Is there a deeper meaning?

The answer is no, and we know that thanks to a mathematical principle called Ramsey theory. So what is Ramsey theory? Simply put, it states that given enough elements in a set or structure, some particular interesting pattern among them is guaranteed to emerge.

The mathematician T.S. Motzkin once remarked that, “while disorder is more probable in general, complete disorder is impossible.” The sheer size of the Universe guarantees that some of its random elements will fall into specific arrangements, and because we evolved to notice patterns and pick out signals among the noise, we are often tempted to find intentional meaning where there may not be any. So while we may be awed by hidden messages in everything from books, to pieces of toast, to the night sky, their real origin is usually our own minds.

From the TED-Ed Lesson The origin of countless conspiracy theories - PatrickJMT

Animation by Aaron, Sean & Mathias Studios

Finding Your Way Around in an Uncertain World

Suppose you woke up in your bedroom with the lights off and wanted to get out. While heading toward the door with your arms out, you would predict the distance to the door based on your memory of your bedroom and the steps you have already made. If you touch a wall or furniture, you would refine the prediction. This is an example of how important it is to supplement limited sensory input with your own actions to grasp the situation. How the brain comprehends such a complex cognitive function is an important topic of neuroscience.

Dealing with limited sensory input is also a ubiquitous issue in engineering. A car navigation system, for example, can predict the current position of the car based on the rotation of the wheels even when a GPS signal is missing or distorted in a tunnel or under skyscrapers. As soon as the clean GPS signal becomes available, the navigation system refines and updates its position estimate. Such iteration of prediction and update is described by a theory called “dynamic Bayesian inference.”

In a collaboration of the Neural Computation Unit and the Optical Neuroimaging Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), Dr. Akihiro Funamizu, Prof. Bernd Kuhn, and Prof. Kenji Doya analyzed the brain activity of mice approaching a target under interrupted sensory inputs. This research is supported by the MEXT Kakenhi Project on “Prediction and Decision Making” and the results were published online in Nature Neuroscience on September 19th, 2016.

The team performed surgeries in which a small hole was made in the skulls of mice and a glass cover slip was implanted onto each of their brains over the parietal cortex. Additionally, a small metal headplate was attached in order to keep the head still under a microscope. The cover slip acted as a window through which researchers could record the activities of hundreds of neurons using a calcium-sensitive fluorescent protein that was specifically expressed in neurons in the cerebral cortex. Upon excitation of a neuron, calcium flows into the cell, which causes a change in fluorescence of the protein. The team used a method called two-photon microscopy to monitor the change in fluorescence from the neurons at different depths of the cortical circuit (Figure 1).

(Figure 1: Parietal Cortex. A depiction of the location of the parietal cortex in a mouse brain can be seen on the left. On the right, neurons in the parietal cortex are imaged using two-photon microscopy)

The research team built a virtual reality system in which a mouse can be made to believe it was walking around freely, but in reality, it was fixed under a microscope. This system included an air-floated Styrofoam ball on which the mouse can walk and a sound system that can emit sounds to simulate movement towards or past a sound source (Figure 2).

(Figure 2: Acoustic Virtual Reality System. Twelve speakers are placed around the mouse. The speakers generate sound based on the movement of the mouse running on the spherical treadmill (left). When the mouse reaches the virtual sound source it will get a droplet of sugar water as a reward)

An experimental trial starts with a sound source simulating a distance from 67 to 134 cm in front of and 25 cm to the left of the mouse. As the mouse steps forward and rotates the ball, the sound is adjusted to mimic the mouse approaching the source by increasing the volume and shifting in direction. When the mouse reaches just by the side of the sound source, drops of sugar water come out from a tube in front of the mouse as a reward for reaching the goal. After the mice learn that they will be rewarded at the goal position, they increase licking the tube as they come closer to the goal position, in expectation of the sugar water.

The team then tested what happens if the sound is removed for certain simulated distances in segments of about 20 cm. Even when the sound is not given, the mice increase licking as they came closer to the goal position in anticipation of the reward (Figure 3). This means that the mice predicted the goal distance based on their own movement, just like the dynamic Bayesian filter of a car navigation system predicts a car’s location by rotation of tires in a tunnel. Many neurons changed their activities depending on the distance to the target, and interestingly, many of them maintained their activities even when the sound was turned off. Additionally, when the team injects a drug that suppresses neural activities in a region of the mice’s brains, called the parietal cortex they find that the mice did not increase licking when the sound is omitted. This suggests that the parietal cortex plays a role in predicting the goal position.

(Figure 3: Estimation of the goal distance without sound. Mice are eager to find the virtual sound source to get the sugar water reward. When the mice get closer to the goal, they increase licking in expectation of the sugar water reward. They increased licking when the sound is on but also when the sound is omitted. This result suggests that mice estimate the goal distance by taking their own movement into account)

In order to further explore what the activity of these neurons represents, the team applied a probabilistic neural decoding method. Each neuron is observed for over 150 trials of the experiment and its probability of becoming active at different distances to the goal could be identified. This method allowed the team to estimate each mouse’s distance to the goal from the recorded activities of about 50 neurons at each moment. Remarkably, the neurons in the parietal cortex predict the change in the goal distance due to the mouse’s movement even in the segments where sound feedback was omitted (Figure 4). When the sound was given, the predicted distance from the sound became more accurate. These results show that the parietal cortex predicts the distance to the goal due to the mouse’s own movements even when sensory inputs are missing and updates the prediction when sensory inputs are available, in the same form as dynamic Bayesian inference.

(Figure 4: Distance estimation in the parietal cortex utilizes dynamic Bayesian inference. Probabilistic neural decoding allows for the estimation of the goal distance from neuronal activity imaged from the parietal cortex. Neurons could predict the goal distance even during sound omissions. The prediction became more accurate when sound was given. These results suggest that the parietal cortex predicts the goal distance from movement and updates the prediction with sensory inputs, in the same way as dynamic Bayesian inference)

The hypothesis that the neural circuit of the cerebral cortex realizes dynamic Bayesian inference has been proposed before, but this is the first experimental evidence showing that a region of the cerebral cortex realizes dynamic Bayesian inference using action information. In dynamic Bayesian inference, the brain predicts the present state of the world based on past sensory inputs and motor actions. “This may be the basic form of mental simulation,” Prof. Doya says. Mental simulation is the fundamental process for action planning, decision making, thought and language. Prof. Doya’s team has also shown that a neural circuit including the parietal cortex was activated when human subjects performed mental simulation in a functional MRI scanner. The research team aims to further analyze those data to obtain the whole picture of the mechanism of mental simulation.

Understanding the neural mechanism of mental simulation gives an answer to the fundamental question of “How are thoughts formed?” It should also contribute to our understanding of the causes of psychiatric disorders caused by flawed mental simulation, such as schizophrenia, depression, and autism. Moreover, by understanding the computational mechanisms of the brain, it may become possible to design robots and programs that think like the brain does. This research contributes to the overall understanding of how the brain allows us to function.

winter sunrise reflections

by Denny Bitte

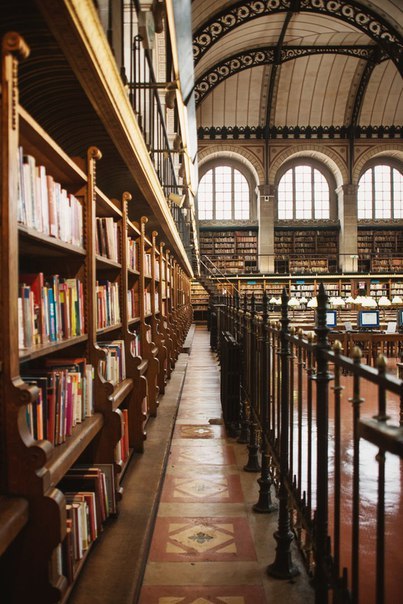

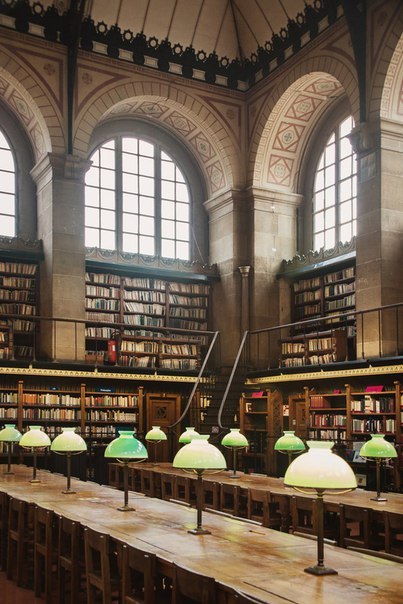

Sainte-Geneviève Library. Paris, France.

(Image caption: New model mimics the connectivity of the brain by connecting three distinct brain regions on a chip. Credit: Disease Biophysics Group/Harvard University)

Multiregional brain on a chip

Harvard University researchers have developed a multiregional brain-on-a-chip that models the connectivity between three distinct regions of the brain. The in vitro model was used to extensively characterize the differences between neurons from different regions of the brain and to mimic the system’s connectivity.

The research was published in the Journal of Neurophysiology.

“The brain is so much more than individual neurons,” said Ben Maoz, co-first author of the paper and postdoctoral fellow in the Disease Biophysics Group in the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “It’s about the different types of cells and the connectivity between different regions of the brain. When modeling the brain, you need to be able to recapitulate that connectivity because there are many different diseases that attack those connections.”

“Roughly twenty-six percent of the US healthcare budget is spent on neurological and psychiatric disorders,” said Kit Parker, the Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics Building at SEAS and Core Faculty Member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. “Tools to support the development of therapeutics to alleviate the suffering of these patients is not only the human thing to do, it is the best means of reducing this cost.“

Researchers from the Disease Biophysics Group at SEAS and the Wyss Institute modeled three regions of the brain most affected by schizophrenia — the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

They began by characterizing the cell composition, protein expression, metabolism, and electrical activity of neurons from each region in vitro.

“It’s no surprise that neurons in distinct regions of the brain are different but it is surprising just how different they are,” said Stephanie Dauth, co-first author of the paper and former postdoctoral fellow in the Disease Biophysics Group. “We found that the cell-type ratio, the metabolism, the protein expression and the electrical activity all differ between regions in vitro. This shows that it does make a difference which brain region’s neurons you’re working with.”

Next, the team looked at how these neurons change when they’re communicating with one another. To do that, they cultured cells from each region independently and then let the cells establish connections via guided pathways embedded in the chip.

The researchers then measured cell composition and electrical activity again and found that the cells dramatically changed when they were in contact with neurons from different regions.

“When the cells are communicating with other regions, the cellular composition of the culture changes, the electrophysiology changes, all these inherent properties of the neurons change,” said Maoz. “This shows how important it is to implement different brain regions into in vitro models, especially when studying how neurological diseases impact connected regions of the brain.”

To demonstrate the chip’s efficacy in modeling disease, the team doped different regions of the brain with the drug Phencyclidine hydrochloride — commonly known as PCP — which simulates schizophrenia. The brain-on-a-chip allowed the researchers for the first time to look at both the drug’s impact on the individual regions as well as its downstream effect on the interconnected regions in vitro.

The brain-on-a-chip could be useful for studying any number of neurological and psychiatric diseases, including drug addiction, post traumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.

"To date, the Connectome project has not recognized all of the networks in the brain,” said Parker. “In our studies, we are showing that the extracellular matrix network is an important part of distinguishing different brain regions and that, subsequently, physiological and pathophysiological processes in these brain regions are unique. This advance will not only enable the development of therapeutics, but fundamental insights as to how we think, feel, and survive.”

Faster, smaller, more powerful computer chips: Hafnia dons a new face

Materials research creates potential for improved computer chips and transistors

It’s a material world, and an extremely versatile one at that, considering its most basic building blocks – atoms – can be connected together to form different structures that retain the same composition.

Diamond and graphite, for example, are but two of the many polymorphs of carbon, meaning that both have the same chemical composition and differ only in the manner in which their atoms are connected. But what a world of difference that connectivity makes: The former goes into a ring and costs thousands of dollars, while the latter has to sit content within a humble pencil.

The inorganic compound hafnium dioxide commonly used in optical coatings likewise has several polymorphs, including a tetragonal form with highly attractive properties for computer chips and other optical elements. However, because this form is stable only at temperatures above 3100 degrees Fahrenheit – think blazing inferno – scientists have had to make do with its more limited monoclinic polymorph. Until now.

Read more.

Tuz Gölü - Cereal / WORDS & PHOTOS: Peter Edel

FOR THE AMERICAN COLOUR FIELD PAINTER BARNETT NEWMAN, THE EMPTY, BOUNDLESS LANDSCAPE ENHANCED AN INDIVIDUAL’S SENSE OF PRESENCE WITHIN THEM. THE TUZ GÖLÜ, THE SALT LAKE LOCATED IN THE CORE OF TURKEY’S ANATOLIAN PENINSULA, IS ONE OF THE PLACES IN THE WORLD WHERE THIS UNDERSTANDING IS EXPERIENCED MOST PROFOUNDLY.

-

mmsouy liked this · 6 years ago

mmsouy liked this · 6 years ago -

dubiousspectrum reblogged this · 6 years ago

dubiousspectrum reblogged this · 6 years ago -

lazzie-writes reblogged this · 6 years ago

lazzie-writes reblogged this · 6 years ago -

lazzie-writes liked this · 6 years ago

lazzie-writes liked this · 6 years ago -

chichennuggies liked this · 6 years ago

chichennuggies liked this · 6 years ago -

zulnuts liked this · 7 years ago

zulnuts liked this · 7 years ago -

optimisticmiraclellama-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago

optimisticmiraclellama-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago -

deadlock liked this · 7 years ago

deadlock liked this · 7 years ago -

asynjadis reblogged this · 8 years ago

asynjadis reblogged this · 8 years ago -

asynjadis liked this · 8 years ago

asynjadis liked this · 8 years ago -

bas1l liked this · 8 years ago

bas1l liked this · 8 years ago -

tacocat-awkwardness liked this · 8 years ago

tacocat-awkwardness liked this · 8 years ago -

gravityinglass reblogged this · 8 years ago

gravityinglass reblogged this · 8 years ago -

minjiminjiminji reblogged this · 8 years ago

minjiminjiminji reblogged this · 8 years ago -

minjiminjiminji liked this · 8 years ago

minjiminjiminji liked this · 8 years ago -

fhecimfummu-blog liked this · 8 years ago

fhecimfummu-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

psychicvelociraptor liked this · 8 years ago

psychicvelociraptor liked this · 8 years ago -

superengineermind-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

superengineermind-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

deathbyparadox liked this · 8 years ago

deathbyparadox liked this · 8 years ago -

jetshelper liked this · 8 years ago

jetshelper liked this · 8 years ago -

bonczellini liked this · 8 years ago

bonczellini liked this · 8 years ago -

polishingopals reblogged this · 8 years ago

polishingopals reblogged this · 8 years ago -

sweaty-men liked this · 8 years ago

sweaty-men liked this · 8 years ago -

misty-anne reblogged this · 8 years ago

misty-anne reblogged this · 8 years ago -

jmaxchill reblogged this · 8 years ago

jmaxchill reblogged this · 8 years ago -

joker-of-gotham reblogged this · 8 years ago

joker-of-gotham reblogged this · 8 years ago -

crittersdoingstuff reblogged this · 8 years ago

crittersdoingstuff reblogged this · 8 years ago -

ominous-prognisticks reblogged this · 8 years ago

ominous-prognisticks reblogged this · 8 years ago -

piccolo-deis reblogged this · 8 years ago

piccolo-deis reblogged this · 8 years ago -

hoochmonster liked this · 8 years ago

hoochmonster liked this · 8 years ago -

pilotbay1 liked this · 8 years ago

pilotbay1 liked this · 8 years ago -

mdwhite101-official liked this · 8 years ago

mdwhite101-official liked this · 8 years ago -

artisanidiot reblogged this · 8 years ago

artisanidiot reblogged this · 8 years ago -

artisanidiot liked this · 8 years ago

artisanidiot liked this · 8 years ago -

rake-moms liked this · 8 years ago

rake-moms liked this · 8 years ago -

thehomo-sapiensagenda liked this · 8 years ago

thehomo-sapiensagenda liked this · 8 years ago -

massivetreechild liked this · 8 years ago

massivetreechild liked this · 8 years ago