Complex Learning Dismantles Barriers In The Brain

Complex learning dismantles barriers in the brain

Biology lessons teach us that the brain is divided into separate areas, each of which processes a specific sense. But findings published in eLife show we can supercharge it to be more flexible.

Scientists at the Jagiellonian University in Poland taught Braille to sighted individuals and found that learning such a complex tactile task activates the visual cortex, when you’d only expect it to activate the tactile one.

“The textbooks tell us that the visual cortex processes visual tasks while the tactile cortex, called the somatosensory cortex, processes tasks related to touch,” says lead author Marcin Szwed from Jagiellonian University.

“Our findings tear up that view, showing we can establish new connections if we undertake a complex enough task and are given long enough to learn it.”

The findings could have implications for our power to bend different sections of the brain to our will by learning other demanding skills, such as playing a musical instrument or learning to drive. The flexibility occurs because the brain overcomes the normal division of labour and establishes new connections to boost its power.

It was already known that the brain can reorganize after a massive injury or as a result of massive sensory deprivation such as blindness. The visual cortex of the blind, deprived of its input, adapts for other tasks such as speech, memory, and reading Braille by touch. There has been speculation that this might also be possible in the normal, adult brain, but there has been no conclusive evidence.

“For the first time we’re able to show that large-scale reorganization is a viable mechanism that the sighted, adult brain is able to recruit when it is sufficiently challenged,” says Szwed.

Over nine months, 29 volunteers were taught to read Braille while blindfolded. They achieved reading speeds of between 0 and 17 words per minute. Before and after the course, they took part in a functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) experiment to test the impact of their learning on regions of the brain. This revealed that following the course, areas of the visual cortex, particularly the Visual Word Form Area, were activated and that connections with the tactile cortex were established.

In an additional experiment using transcranial magnetic stimulation, scientists applied magnetic field from a coil to selectively suppress the Visual Word Form Area in the brains of nine volunteers. This impaired their ability to read Braille, confirming the role of this site for the task. The results also discount the hypothesis that the visual cortex could have just been activated because volunteers used their imaginations to picture Braille dots.

“We are all capable of retuning our brains if we’re prepared to put the work in,” says Szwed.

He asserts that the findings call for a reassessment of our view of the functional organization of the human brain, which is more flexible than the brains of other primates.

“The extra flexibility that we have uncovered might be one those features that made us human, and allowed us to create a sophisticated culture, with pianos and Braille alphabet,” he says.

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

Look! A scientist who says more scrutiny is needed! Yea!

AND - “Don’t try this at home!”

Cadaver study casts doubts on how zapping brain may boost mood, relieve pain

Earlier this month, György Buzsáki of New York University (NYU) in New York City showed a slide that sent a murmur through an audience in the Grand Ballroom of New York’s Midtown Hilton during the annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. It wasn’t just the grisly image of a human cadaver with more than 200 electrodes inserted into its brain that set people whispering; it was what those electrodes detected—or rather, what they failed to detect.

When Buzsáki and his colleague, Antal Berényi, of the University of Szeged in Hungary, mimicked an increasingly popular form of brain stimulation by applying alternating electrical current to the outside of the cadaver’s skull, the electrodes inside registered little. Hardly any current entered the brain. On closer study, the pair discovered that up to 90% of the current had been redirected by the skin covering the skull, which acted as a “shunt,” Buzsáki said.

The new, unpublished cadaver data make dramatic effects on neurons unlikely, Buzsáki says. Most tDCS and tACS devices deliver about 1 to 2 milliamps of current. Yet based on measurements from electrodes inside multiple cadavers, Buzsaki calculated that at least 4 milliamps—roughly equivalent to the discharge of a stun gun—would be necessary to stimulate the firing of living neurons inside the skull. Buzsáki notes he got dizzy when he tried 5 milliamps on his own scalp. “It was alarming,” he says, warning people not to try such intense stimulation at home.

Buzsáki expects a living person’s skin would shunt even more current away from the brain because it is better hydrated than a cadaver’s scalp. He agrees, however, that low levels of stimulation may have subtle effects on the brain that fall short of triggering neurons to fire. Electrical stimulation might also affect glia, brain cells that provide neurons with nutrients, oxygen, and protection from pathogens, and also can influence the brain’s electrical activity. “Further questions should be asked” about whether 1- to 2-milliamp currents affect those cells, he says.

Buzsáki, who still hopes to use such techniques to enhance memory, is more restrained than some critics. The tDCS field is “a sea of bullshit and bad science—and I say that as someone who has contributed some of the papers that have put gas in the tDCS tank,” says neuroscientist Vincent Walsh of University College London. “It really needs to be put under scrutiny like this.”

On this date in 1884, the first edition of what would become the Oxford English Dictionary was published under the name A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. Research for the OED had begun in 1857, when the Philological Society in London established an “Unregistered Words Committee” to find words that were either poorly defined, or absent from contemporary dictionaries. When the list of unregistered words outnumbered the amount of words found in nineteenth-century dictionaries, the group decided to write their own. The Oxford University Press agreed to publish the dictionary in 1879, and the group published the first fascicle – which covered A to Ant –in 1884 to disappointing sales. It wasn’t until 1928 that the final fascicle was published, totaling 128 fascicles in total.

In 1933, a thirteen-volume set including all fascicles and a one-volume supplement went on sale under its current name: Oxford English Dictionary – only seventy-six years in the making!

Pictured above is our well-loved copy of that historic first fascicle, which includes the preface to the dictionary and entries A through Ant. While the volume is huge and a little intimidating, it was only the beginning to what would become the most comprehensive dictionary in the English language.

Ed. James A.H. Murray. A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society v. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1888. 423 M96 v. 1.

Le festival Sōma-shi 相馬市 - préfecture de Fukushima-ken 福島県.

La région de Sōma est réputée pour ses chevaux. Tous les ans, du 22 au 25 juillet, s'y déroule le Sōma nomaoi 相馬野馬追, littéralement : “chasse aux chevaux sauvages de Sōma” autour des sanctuaires Ōta jinja 太田神社 et Odaka jinja 小高神社 à Minamisōma-shi 南相馬市, et du sanctuaire Nakamura jinja 中村神社 à Sōma. Durant 3 jours, les anciens cavaliers samouraïs sont mis à l’honneur lors de différentes démonstrations, parades de samouraïs, courses de chevaux, reconstitutions de batailles et processions.

A whole lot of books

In 1610, after successfully rebuilding, reopening and firmly establishing the Bodleian Library, Sir Thomas Bodley made it his new goal to ensure the library’s long-term relevance. He forged an agreement with the Stationers’ Company that saw his library receive one copy of everything printed under royal license. This would guarantee that the Bodleian would continue to be at the cutting edge of literature and librarianship.

And this was when the Bodleian became, by effect, the first Legal Deposit library in the UK. From 1662, the notions were solidified and the Royal Library and the University Library of Cambridge were also party to the same privileges. Until the establishment of the British Library in 1753, the university libraries of Oxford and Cambridge - especially the Bodleian Library, which had enjoyed the legal deposit privilege the longest – served as the de facto national libraries of the United Kingdom.

But what’s the current state of Legal Deposit at the Bodleian? And, as @LowlandsLady asked us on Twitter, might it ever feel like a curse to have this multitude of books rolling into the library?

There’s nobody better to answer these questions than Jackie Raw, Head of Legal Deposit Operations in our Collections Management department. From this point on, this Tumblr post belongs to Jackie.

The Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003 obliges publishers to deposit, at their own cost, one copy of every printed publication that is published or distributed in the UK with the British Library and, upon request, with up to five other Legal Deposit Libraries of which the Bodleian is one.

These Legal Deposit Libraries seek to ensure that the UK published output is preserved for posterity. To do this the requesting libraries together use the Agency for the Legal Deposit Libraries. The Agency makes claims for titles on our behalf and, on receipt, these are recorded and distributed weekly to the libraries. By collaborating the Legal Deposit Libraries seek to develop and co-ordinate national coverage and preservation of, and access to, publications acquired by legal deposit.

A random selection of books arriving by Legal Deposit.

While the Legal Deposit system has existed in various forms since 1662, the reformed Act in 2003 extended the provision for printed material to cover non-print works. This brings new and emerging publishing media under its scope. The Regulations for this came into force in April 2013. We now have the opportunity to add e-books, e-journals, digital maps and digital music scores to our collections and to harvest and archive content from UK-published material on UK websites under the new legislation.

Again the libraries are working together to ensure coverage. The benefits of holding a collection of over 12 million physical items, much of which has been deposited under Legal Deposit, and a growing digital collection cannot be overstated.

A recent count of books arriving daily at the Bodleian Libraries.

Legal Deposit ensures the nation’s heritage is collected systematically and preserved for posterity. It supports and advances the teaching and research activities of the University of Oxford and national and international scholarship more widely by collecting, recording and making available this material and it provides, in a cost-effective way, access to a wide range of publications many of which are unlikely to be found outside of the Legal Deposit system.

However, it is also a responsibility.

Clearly there can be pressures on space, storage and transportation. There are staff levels and processing costs to consider and issues around funding limitations. On the other hand there is provision within the Act to allow libraries, other than the British Library, to be selective in what we acquire. So, by consulting and collaborating we aim to ensure as complete coverage as possible within resourcing limits without overburdening any one library with the rate at which our collections are growing.

David in Singapore, Serious Moonlight Tour 1983

Photo © Denis O’Regan

Dau lun o weithwyr G P Lloyd & Co, Dumballs Rd, Caerdydd, gwneuthurwyr coesau pren i offer, c. 1930, ond beth yw'r gwahaniaeth rhwng y ddau?

-

Two photos of workers at G P Lloyd & Co, Dumballs Road, Cardiff, manufacturers of wooden tool handles, c. 1930. Can you spot the difference?

From the archives at St Fagans National Museum of History.

Joan Beauchamp Procter: her best friend was a Komodo dragon and if that doesn’t entice you to read this, I don’t know what will

Joan Beauchamp Procter is a scientist every reptile enthusiast should admire.

Joan was an incredibly intelligent young woman who was chronically ill (and as a result of her chronic illness, physically disabled by her early thirties). Her health issues kept her from going to college, but that did not stop her from studying and keeping reptiles. She presented her first paper to the Zoological Society of London at the tender age of nineteen, and the society was so impressed that they hired her to help design their aquarium. In 1923, despite having no formal secondary education and despite being only 26 years old, she was hired as the London Zoo’s curator of reptiles. Now, that in and of itself is an awesome accomplishment, but Joan was absolutely not content to maintain the status quo. Nosiree, by the age of 26 Joan had already kept many exotic pets (including a crocodile!) and knew a thing or two about what needed to be done to improve their lives in captivity. So Joan got together with an architect, Edward Guy Dawber, and designed the world’s first building designed solely for the keeping of reptiles. She had some really, really great ideas. Her first big idea was to make the building differentially heated- different areas and enclosures would have different heat zones, instead of having the whole building heated to one warm temperature. She also set up aquarium lighting- the gallery itself was dark, with dim lights on individual enclosures to make things less stressful for the inhabitants. She also insisted on the use of special glass that didn’t filter out UVB. This meant that reptiles could synthesize vitamin D and prevented cases of MBD in her charges.

But advances in enclosure design weren’t Joan’s only contribution to reptile keeping. She was also one of the first herpetologists to study albinism in snakes- she was the first to publish an identification how albinism manifests in reptile eyes differently than in mammal eyes, and stressed the importance of making accurate color plates of reptiles during life because study specimens often lose pigmentation. She also was really hands-on with many species, including crocodiles, large constrictors, and monitor lizards. Joan had this idea that if you socialize an animal and get it used to handling, then when you need to give it a vet checkup, things tend to go a lot better. This really hadn’t been done with reptiles before. She was able to identify many unstudied diseases, thanks to her patient handling of live specimens, and by being patient and going slow, she managed to get a lot of very large, dangerous creatures to trust her. One of them (that we know of) even came to like her- a Komodo dragon named Sumbawa.

In 1928, two of the first Komodo dragons to be imported to Europe arrived at the London Zoo. One of them, named Sumbawa, came in with a nasty mouth infection. His first several months at the zoo were a steady stream of antibiotics and gentle care, and by the time he’d recovered enough for display, he had come to be tolerant of handling and human interaction. In particular, he seemed to be genuinely fond of Joan. She was their primary caretaker and wrote many of the first popular accounts of Komodo dragon behavior in captivity. While recognizing their lethal capacity, she also wrote about how smart they are and how inquisitive they could be. In her account published in The Wonders of Animal Life, she said that "they could no doubt kill one if they wished, or give a terrible bite" but also that they were “as tame as dogs and even seem to show affection.” To demonstrate this, she would take Sumbawa around on a leash and let zoo visitors interact with him. She would also hand-feed Sumbawa- pigeons and chickens were noted to be favorite food, as were eggs.

Joan died in 1931 at the age of 34. By that time she was Doctor Procter, as the University of Chicago had awarded her an honorary doctorate. Until her death, she still remained active with the Zoological Society of London- and she was still in charge of her beloved reptiles. Towards the end of her life, Joan needed a wheelchair. But that didn’t stop her from hanging out with her giant lizard friend. Sumbawa would walk out in front of the wheelchair or beside it, still on leash- she’d steer him by touching his tail. At her death, she was one of the best-known and respected herpetologists in the world, and her innovative techniques helped shape the future of reptile care.

Beautiful Blaschka glass model of a Glaucus sea slug.

These amazing animals can give a painful sting if handled. This is because they feed on colonial cnidarians such as Portuguese man o’ war and store the venomous nematocysts of their prey for self-protection.

Oval Eggs

The word egg was a borrowing from Old Norse egg, replacing the native word ey (plural eyren) from Old English ǣġ, plural ǣġru. Like “children” and “kine” (obsolete plural of cow), the plural ending -en was added redundantly to the plural form in Middle English. As with most borrowings from Old Norse, this showed up first in northern dialects of English, and gradually moved southwards, so that for a while, ey and egg were used in different parts of England.

In 1490, when William Caxton printed the first English-language books, he wrote a prologue to his publication of Eneydos (Aeneid in contemporary English) in which he discussed the problems of choosing a dialect to publish in, due to the wide variety of English dialects that existed at the time. This word was a specific example he gave. He told a story about some merchants from London travelling down the Thames and stopping in a village in Kent

And one of theym… cam in to an hows and axed for mete and specyally he axyd after eggys, and the goode wyf answerde that she could speke no Frenshe. And the marchaunt was angry, for he also coude speke no Frenshe, but wolde have hadde egges; and she understode hym not. And thenne at laste a-nother sayd that he wolde have eyren. Then the good wyf sayd that she understod hym wel. Loo, what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte, egges, or eyren? Certaynly it is hard to playse every man, by-cause of dyversite and chaunge of langage.

The merchant in this story was only familiar with the word egg, while the woman only knew ey, and the confusion was only resolved by someone who knew both words. Indeed, the woman in the story was so confused by this unfamiliar word egg that she assumed it must be a French word! The word “meat” (or “mete” as Caxton spelled it) was a generic word for “food” at the time.

The word ey may also survive in the term Cockney, thought to derive from the Middle English cocken ey (”cock’s egg”), a term given to a small misshapen egg, and applied by rural people to townspeople

Both egg and ey derived from the same Proto-Germanic root, *ajją, which apparently had a variant *ajjaz in West Germanic. This Proto-Germanic form in turn derived from Proto-Indo-European *h2ōwyóm. In Latin, this root became ōvum, from which the adjective ōvalis meaning “egg-shaped”, was derived. Ōvum itself was borrowed into English in the biological sense of the larger gamete in animals, while ōvalis is the source of oval.

The PIE root is generally though to derive from the root *h2éwis, “bird”, which is the source of Latin avis “bird”, source of English terms such as aviation. This word may also be related to *h2ówis “sheep”, which survived in English as ewe. One theory is that they were both derived from a root meaning something like “to dress”, “to clothe”, with bird meaning “one who is clothed [in feathers]” and sheep meaning “one who clothes [by producing wool]”.

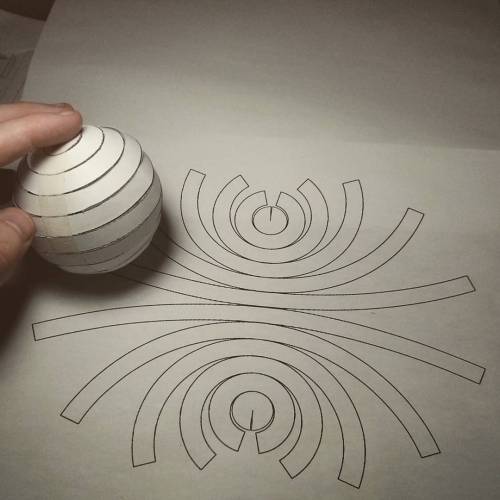

Can you flatten a sphere?

The answer is NO, you can not. This is why all map projections are innacurate and distorted, requiring some form of compromise between how accurate the angles, distances and areas in a globe are represented.

This is all due to Gauss’s Theorema Egregium, which dictates that you can only bend surfaces without distortion/stretching if you don’t change their Gaussian curvature.

The Gaussian curvature is an intrinsic and important property of a surface. Planes, cylinders and cones all have zero Gaussian curvature, and this is why you can make a tube or a party hat out of a flat piece of paper. A sphere has a positive Gaussian curvature, and a saddle shape has a negative one, so you cannot make those starting out with something flat.

If you like pizza then you are probably intimately familiar with this theorem. That universal trick of bending a pizza slice so it stiffens up is a direct result of the theorem, as the bend forces the other direction to stay flat as to maintain zero Gaussian curvature on the slice. Here’s a Numberphile video explaining it in more detail.

However, there are several ways to approximate a sphere as a collection of shapes you can flatten. For instance, you can project the surface of the sphere onto an icosahedron, a solid with 20 equal triangular faces, giving you what it is called the Dymaxion projection.

The Dymaxion map projection.

The problem with this technique is that you still have a sphere approximated by flat shapes, and not curved ones.

One of the earliest proofs of the surface area of the sphere (4πr2) came from the great Greek mathematician Archimedes. He realized that he could approximate the surface of the sphere arbitrarily close by stacks of truncated cones. The animation below shows this construction.

The great thing about cones is that not only they are curved surfaces, they also have zero curvature! This means we can flatten each of those conical strips onto a flat sheet of paper, which will then be a good approximation of a sphere.

So what does this flattened sphere approximated by conical strips look like? Check the image below.

But this is not the only way to distribute the strips. We could also align them by a corner, like this:

All of this is not exactly new, of course, but I never saw anyone assembling one of these. I wanted to try it out with paper, and that photo above is the result.

It’s really hard to put together and it doesn’t hold itself up too well, but it’s a nice little reminder that math works after all!

Here’s the PDF to print it out, if you want to try it yourself. Send me a picture if you do!

-

jera349 liked this · 7 years ago

jera349 liked this · 7 years ago -

blext liked this · 7 years ago

blext liked this · 7 years ago -

twix1010 liked this · 8 years ago

twix1010 liked this · 8 years ago -

twix1010 reblogged this · 8 years ago

twix1010 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

maciorka liked this · 8 years ago

maciorka liked this · 8 years ago -

flava-slav reblogged this · 8 years ago

flava-slav reblogged this · 8 years ago -

klarastjarnljus reblogged this · 8 years ago

klarastjarnljus reblogged this · 8 years ago -

gopalsingh00 reblogged this · 8 years ago

gopalsingh00 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

anothergil reblogged this · 9 years ago

anothergil reblogged this · 9 years ago -

dozyzay liked this · 9 years ago

dozyzay liked this · 9 years ago -

soundgrammar liked this · 9 years ago

soundgrammar liked this · 9 years ago -

iyeshaisriley reblogged this · 9 years ago

iyeshaisriley reblogged this · 9 years ago -

lightphotons liked this · 9 years ago

lightphotons liked this · 9 years ago -

themoonghosts reblogged this · 9 years ago

themoonghosts reblogged this · 9 years ago -

convoluted-moonscape reblogged this · 9 years ago

convoluted-moonscape reblogged this · 9 years ago -

convoluted-moonscape liked this · 9 years ago

convoluted-moonscape liked this · 9 years ago -

sweetsurrenderdoll liked this · 9 years ago

sweetsurrenderdoll liked this · 9 years ago -

hypno-panavatar reblogged this · 9 years ago

hypno-panavatar reblogged this · 9 years ago -

geezelouise8 reblogged this · 9 years ago

geezelouise8 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

edmunsen reblogged this · 9 years ago

edmunsen reblogged this · 9 years ago -

edmunsen liked this · 9 years ago

edmunsen liked this · 9 years ago -

enetiertianingentp reblogged this · 9 years ago

enetiertianingentp reblogged this · 9 years ago -

somekindofelvish liked this · 9 years ago

somekindofelvish liked this · 9 years ago -

platinumediting-blog liked this · 9 years ago

platinumediting-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

loafyloaf liked this · 9 years ago

loafyloaf liked this · 9 years ago -

cattfartts-blog liked this · 9 years ago

cattfartts-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

uppernoclass liked this · 9 years ago

uppernoclass liked this · 9 years ago -

the-linquisition reblogged this · 9 years ago

the-linquisition reblogged this · 9 years ago -

sirfernandoborges-blog liked this · 9 years ago

sirfernandoborges-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

sirfernandoborges-blog reblogged this · 9 years ago

sirfernandoborges-blog reblogged this · 9 years ago -

paisiblement liked this · 9 years ago

paisiblement liked this · 9 years ago -

xampai reblogged this · 9 years ago

xampai reblogged this · 9 years ago -

xampai liked this · 9 years ago

xampai liked this · 9 years ago -

usernamegeneric55-blog liked this · 9 years ago

usernamegeneric55-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

eka-mark liked this · 9 years ago

eka-mark liked this · 9 years ago -

studyinglogic reblogged this · 9 years ago

studyinglogic reblogged this · 9 years ago -

shooting-stars-andsatellites liked this · 9 years ago

shooting-stars-andsatellites liked this · 9 years ago -

anonymousreviewer-t reblogged this · 9 years ago

anonymousreviewer-t reblogged this · 9 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts