If You’re Offline Or Away And I Message You Something (like A Link To A Meme Or A Picture Or W/e) Honestly

if you’re offline or away and i message you something (like a link to a meme or a picture or w/e) honestly just assume that i’m just leaving it there for when you get back and not expecting you to answer straight away. i don’t need you to respond with “hey, sorry, i wasn’t at the computer!” or anything. i was leaving u a gift for later.

More Posts from Penguka and Others

First Moves (SakuAtsu)

Atsumu had always been the one to make the first move, may it be through messages or asking Kyoomi out for dates. Kiyoomi got so accustomed to it that he panics when Atsumu doesn't message him for an entire day. He goes back to their messages and rereads them.

Everything's fine. Atsumu used emojis, sent him some memes and even some selfies. So, he evaluates his responses to make sure he didn't sound uninterested or check if he could've said something that might've offended Atsumu or put him in a bad mood. But in the end, he found nothing out of the usual.

"Stop overthinking it. He tells you things he doesn't like, so there's no need to panic," Kiyoomi whispers to himself, but he still finds himself pressing the call button.

Kiyoomi hears the ringing, and his heart immediately starts beating erratically.

What if he's busy? What if he finds it annoying? What if everything's fine and I look like I'm too clingy? What if he gets mad?

All these questions keep running in Kiyoomi's head, making it difficult to make the first move. He sighs as his thoughts get the better of him, but before he could even turn off the call, Atsumu's voice pulls him out of his head.

"Hey, Omi-kun! What's up?" Atsumu asks on the other side. Kiyoomi gulps and straightens his back as he tries to keep his composure.

"Nothing," Kiyoomi answers, there's silence on the other side of the line, and this makes Kiyoomi panic once again.

"Oh, then why'd you call?" Atsumu asks. His tone's normal, and yet Kiyoomi still feels like something's off.

"I just missed you," Kiyoomi whispers, it was so small that Atsumu almost didn't catch it, "I'm sorry for bothering you so late at night,"

"What? No, don't apologize! I like it, actually," Atsumu says, "it makes my heart really soft hearing you say you miss me,"

Kiyoomi can imagine Atsumu smiling on the other end of the line, and this made him feel silly for panicking over Atsumu not messaging him.

"So, what now?" Kiyoomi asks as he lays on his bed with a calmer heart and a smile on his face.

"I don't know, tell me about your day. I just slept the entire day, so I don't have much," Atsumu answers.

Kiyoomi smiles, "okay,"

Kiyoomi then proceeds to tell Atsumu about his day, and they ended up talking until past nine. Once Atsumu notices, he says, "Omi, we have to go to sleep. We still have Saturday training,"

"Oh," Kiyoomi says and turns to the clock, "I guess this is good night then,"

"Yeah," Atsumu says, "but before you hang up,"

"What is it?"

"I just wanted you to know that it made me really happy that you called," Atsumu says, making Kiyoomi grin wide, "Then I'll call you more often,"

Kiyoomi doesn't hear a response, but he does hear a muffled scream which makes him chuckle, "Okay, I'll call you tomorrow morning,"

"Okay, Omi-kun, good night. I love you," Atsumu says, making Kiyoomi's heart run wild.

"Good night, I love you too, Atsumu," Kiyoomi says and hangs up before turning on his side and sleeping with a smile on his face now that he knows that making the first move won't annoy Atsumu.

No thoughts, just sexy aswang

Why is this so disconcerting....give me back ugly dokja im begging you

I rendered some characters of the Philippine Mythopoeia book in the style of Renaissance grotesque, with creeping flora, weird fauna, monsters, and deities.

#creating

I remember watching this interview of Hajime Isayama where he said that, when he presented the story of Attack on Titan to its current publishers, he was at the lowest possible point of self-esteem in his life, about himself and about his work, so much so that he was on the brink of giving it all up. It marked me so much because… I was watching this interview precisely because I deeply admired this man’s artistic work. I could not fathom that he would have ever doubted it himself.

It reminded me that you can only trust the work. It really doesn’t matter what your opinion of yourself or your abilities as a creator is. It is entirely irrelevant, even. Worse: it gets in the way of creation. When you focus too much on it, you stop trying and doing. And if there is one thing that cannot be doubted, it is that nothing is achieved without trying and doing. Nothing bad and nothing good.

So really, as long as the desire to create burns your insides and keeps you awake at night and makes your fingers shiver from the need to grab a pen or a brush, there is only one option: keep making. Doubt won’t ever disappear. Creating shall remain this uneasy, vertiginous activity, keeping you on the brink of the abyss.

Follow your guts and have faith in the process. Trust that the work needs to be done, no matter the whims of self-confidence. At the end of the day, your creation may have sprung out of your mind and your knowledge, your experiences and your emotions, your time and your dedication, but it is not you. It may be better; it may be worse; but it is a thing of its own that needs to be done and that only you can do.

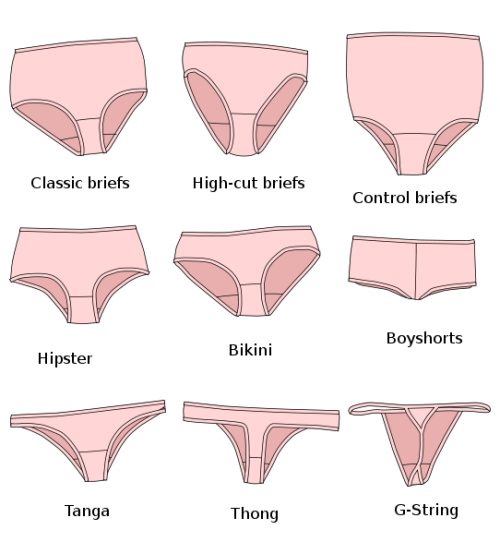

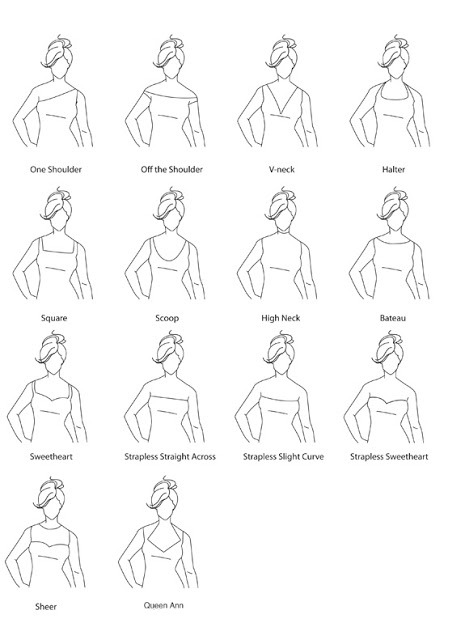

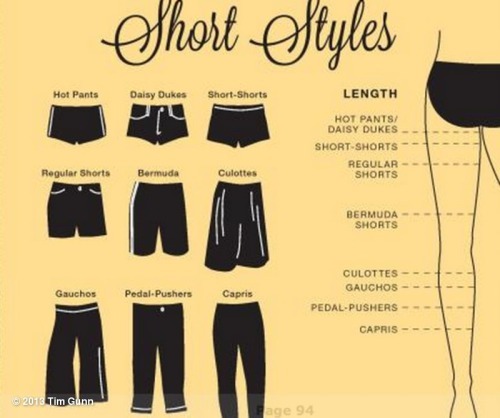

A Visual #Fashion Guide For Women - Necklines, Skirt Types & More!

By KikiCloset.com

Trese, as a story that features various mythological creatures from the Philippines, may give the impression that all these beings belong to only one group. That's not how it is. For one, Ibu and Talagbusao are not from the same pantheon.

This book (PDF) is an introduction to Philippine folk spirituality and religion.

Here's an excerpt relevant to the series.

[Edit 6/14/2021] Just checked. Yep, this is definitely one of Budjette Tan's references. From the Trese: Mass Murders (Visprint ed) afterword:

While doing research for Trese's next villain, I read about the Talagbusao, the god of war, in "The Soul Book" and he sounded like a formidable foe. The more I thought about it, the more it made sense to me that the Kambal needed to be more powerful than any aswang or enkanto.

Transcription:

Assistant Deities and Powers

Below the Lord of the Upper Sky is a host of anitos or diwatas, many of whom can do as they please the more distant they are from him. According to Barton, who studied the Ifugao spirit world (1946), these spirits are believed to be immortal, to change form at will, to become invisible, and to transport themselves quickly through space. There are other attributes associated with these powerful spirits. While they can diagnose and cure illness, they can afflict men with misfortune, ill-luck, disease. They can recover a soul if it has been carried off, but they can also coax away a person's soul. Though they prevent the dead from molesting the living, they too cause death. Indeed they can devour parts of the living human body. Men's minds they influence to suggest courses of conduct, such as payment of debt without losing face; passions they dampen so that men will not fight during a celebration; and stomachs they tie to dull the appetite for food and drink. Those who propitiate them know that these invisible presences can increase rice even after it has been stored in the granary, ward off trespassers, make the hunt safe, and bring victory in battle.

Powerful spirits roughly divide into three categories: ancestor spirits, nature spirits, guardian spirits.

Spirits of Ancestral Heroes

Some ancestors, particularly those who were outstanding in farming, hunting, warfare and the arts, acquired more and more powers in the memory of their descendants as time went on. They became fabulous beings. The more illustrious hero-spirits arc remembered in the great epics. Others arc remembered as culture heroes who taught their people new skills.

Some ancestral heroes (Cole 1916; de los Reyes 1909):

Lumabat - first Bagobo mortal to attain the Skyworld (Cole 1916).

Handiong - the hero of the Bikol epic who freed the land from the ravages of wild animals, brought Bikolanos rice, and planted the fruits.

Lumawig - taught the Bontok headhunting, agriculture, the art of building council houses and men's dwellings, and a code of ethics.

Bantugan - the charming, indestructible, much-wedded hero who could repulse any invasion. His cult probably began when the Maranaws were still animist.

Nature Spirits

Not all ancestral spirits become deified. Many remain nameless spirits residing in dark majestic trees and in the deep woods.

Nature Spirits reside in the natural environment, such as trees, rocks, crags, rivers and volcanoes. Humanlike, but much more powerful, these unseen beings are credited with feelings and sensibilities. Accordingly they may be offended and thus cause harm, or they may be propitiated and their friendship gained. Some spirits are represented as being sensitive to a fault as many Filipinos are when confronted with an unfamiliar or unpleasant situation. People do create spirits according to their likeness. On the other hand Frank Lynch, the anthropologist, says that the Filipino's care in handling interpersonal relations may in fact be the result rather than the cause of this belief in an environment filled with sensitive spirits (1970). In moving about, he takes care not to displease the many invisibles who could punish him.

Nature spirits can be either malevolent or beneficent. As in Philippine society as a whole, it all depends on how you deal with them. If you ignore them and hurt their dignity, they can make you sick; however, if you acknowledge them and ask permission to pass by and give them offerings on occasion, then they will reward you.

Some nature spirits:

The Lord of the Mound - spirit of an old man who lives in a termite mound. Throughout prehistoric Southeast Asia, the earth mound was a locus of power probably because of its phallic shape. "Tabi, tabi po baka kayo mabunggo" (Excuse me, please, lest I bump you) is the polite way to pass one of these inhabited hills. Though invisible, the nuno can be grazed and thus retaliate with a fever or skin rashes.

The Tree Dwellers - Spirits reportedly resided in trees. Thus the Mandayas, who are the largest ethnic group in southwestern Mindanao, believe that tagbanuwa and tagamaling are spirits who dwell in caves and balete trees. The belief persists to this day even among Christian Filipinos. The Ilokano pugot and the Tagalog kapre are gigantic, cigar-smoking black spirits who sit in deserted houses and up a balete or banyan tree with feet dangling to the ground. They can, however, assume any size they want including that of an infant. Engkantos also dwell in trees. But the term itself and the description of them as tall, fair-skinned and light-haired beings with high-bridged noses is post-hispanic. Engkantos, male or female, sometimes fall in love with mortals and lavish gifts on them (Ramos 1971).

The Babes in the Woods- probably the souls of foetuses or dead children. They arc called by the Ilokanos kibaan. The creature is a foot high, dwells in the fields, can be scalded with boiling water, and even die. The kibaan gift friends with gold, a cloak that confers invisibility and a large cup of coconut which is inexhaustible. To those who throw hot water at them, the kibaan scatter powder which produces a disagreeable affliction (de los Reyes 1909). Closely related is the Tagalog patianak which wails in the forest, like a baby, but inflicts harm. Common in pre-Christian times was the practice of exposing infirm deformed babies in the fields and forests (Alcina 1960). Their heart-wrenching wailing must have given rise to these beliefs.

The Bloodthirsty and Implacable

Among traditional Filipinos, the embodiment of evil is a being that is neither fully human nor fully animal. It stands upright like human beings and has a face; but it preys on human flesh and makes the living sick so that when they die there is carrion for food. Unlike the devil of the Judaeo-Christian-Moslem tradition, this being does not harm the soul by tempting it to sin. The death it causes is physical rather than spiritual. Other spirits can be negotiated with: offerings and kind words win their toleration if not help. It is not possible to do so with these implacable beings. Thus people fear them the most.

The busaw feared by the Bagobos of Davao, people the air, the mountains and the forest. They are limitless in number. Most malignant is the busaw called tigbanua. One eye gapes in the middle of the forehead; a hooked chin two spans long upturns to catch the drops of blood that drip from the mouth; and coarse black hair bristles on the body (Benedict 1916). It frequents graves, empty houses and solitary mountain trails. Indeed it may make an appearance at any place outside the safety of one's home.

Guardian Spirits

They are believed to preside over specific human activities such as birth, marriage, and death; over hunting, fishing, farming and fighting. Beneficent and powerful, guardian spirits generally rule from the sky; some, however, stay in their areas of responsibility on earth or in the underworld.

SOME GUARDIAN GODS

ON THE FARM

lkapati- Tagalog goddess of fertility. guardian anito of agriculture

Magbangal - Bukidnon planter god who became the constellation that appears to signal the start of the planting season

Damolag - an anito of the early Zambals who protects the fruiting rice from winds and typhoons

Lakan-bakod - Tagalog guardian god of the fruits of the earth who dwells m certam kinds of plants used as fences. Some anitos carry the title "Lakan" or Prince They could have been deified kinglets

Pamahandi - protector of carabaos and horses of the Bukidnon.

WHEN FISHING

Amansinaya - anito of fishermen of the ancient Tagalogs to whom they offer their first catch. Hence the term pa-sinaya ("for Sinaya") still used today. Following the theory of god-making, Amansinaya could be the soul of a maiden who was drowned and became an anito of the water.

Libtakan- god of sunrise. sunset and good weather of the Manobo.

Makabosog - a merciful diwata of the Bisayans who provides food for the hungry. (He was once a chief in the Araut River on the coast of Panay)

IN THE FORESTS

Amani kable - ancient Tagalog anito of hunters.

Makaboteng - Tinggian spirit guardian of deer and wild hogs.

WHEN REARING A FAMILY

Mingan - goddess of the early Pampangos mate of the god Suku (Consorts of the gods fall under the " guardian" category)

Katambay - guardian anito for individuals, a kind of inborn guardian angel of the Bicols.

Malimbung - a kind of Aphrodite of the Bagobos This goddess made man crave for sexual satisfaction

Tagbibi- diwata protector of children of the mountain tribes of Mindanao

WHILE AT WAR

Mandarangan and Darago - Bagobo god and goddess of war Mandarangan is believed to reside in the crater of Apo Volcano on a throne of fire and blood

Talagbusao - the uncontrollable Bukidnon god of war who takes the form of a warrior with big red eyes wearing a red garment. This deity can enter a mortal warnor's body and make him fight fiercely to avenge a wrong. But Talagbusao can also drive him to insanity by incessant demand for the blood of pigs, fowls and humans.

AT DEATH

Masiken - guardian of the underworld of the lgorots, whose followers have tails

lbu - queen of the Manobo underworld whose abode is down below at the pillars of the world.

This information came from the following sources: Jocano 1969; de los Reyes 1909; Garvan 1931; Garvan 1941; Cole 1922; Benedict 1916; Dadole 1989; Mallari-Wilson 1968

--

Demetrio, F. R., Cordero-Fernando, G. and Zialcita, F. N. (1991). The soul book. GCF Books.

In Philippine Mythology, Mayari is the one-eyed moon goddess of war, beauty, strength, and revolution. By @porkironandwine on twitter

-

ampersand-antics reblogged this · 2 months ago

ampersand-antics reblogged this · 2 months ago -

piep liked this · 2 months ago

piep liked this · 2 months ago -

starrylovessunny reblogged this · 2 months ago

starrylovessunny reblogged this · 2 months ago -

plutos-only-inhabitant liked this · 2 months ago

plutos-only-inhabitant liked this · 2 months ago -

sobbing-quietly02 reblogged this · 2 months ago

sobbing-quietly02 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sobbing-quietly02 liked this · 2 months ago

sobbing-quietly02 liked this · 2 months ago -

sugarnsweets liked this · 2 months ago

sugarnsweets liked this · 2 months ago -

pulmonaryplutonium reblogged this · 2 months ago

pulmonaryplutonium reblogged this · 2 months ago -

addieinfanworld reblogged this · 2 months ago

addieinfanworld reblogged this · 2 months ago -

prismaticproblem58 liked this · 2 months ago

prismaticproblem58 liked this · 2 months ago -

chaotic-cryptid-link liked this · 2 months ago

chaotic-cryptid-link liked this · 2 months ago -

aili-coyote liked this · 2 months ago

aili-coyote liked this · 2 months ago -

puckbees reblogged this · 2 months ago

puckbees reblogged this · 2 months ago -

kinda-wanna-kiss-your-gf reblogged this · 2 months ago

kinda-wanna-kiss-your-gf reblogged this · 2 months ago -

kinda-wanna-kiss-your-gf liked this · 2 months ago

kinda-wanna-kiss-your-gf liked this · 2 months ago -

skulkinspirit reblogged this · 2 months ago

skulkinspirit reblogged this · 2 months ago -

skulkinspirit liked this · 2 months ago

skulkinspirit liked this · 2 months ago -

nephritemoro88 liked this · 2 months ago

nephritemoro88 liked this · 2 months ago -

thegarbageman-can reblogged this · 2 months ago

thegarbageman-can reblogged this · 2 months ago -

thegarbageman-can liked this · 2 months ago

thegarbageman-can liked this · 2 months ago -

rockcreature liked this · 2 months ago

rockcreature liked this · 2 months ago -

muzikrules18-blog liked this · 2 months ago

muzikrules18-blog liked this · 2 months ago -

hhover liked this · 2 months ago

hhover liked this · 2 months ago -

undecided-musician liked this · 2 months ago

undecided-musician liked this · 2 months ago -

asymmetryestablished reblogged this · 2 months ago

asymmetryestablished reblogged this · 2 months ago -

asymmetryestablished liked this · 2 months ago

asymmetryestablished liked this · 2 months ago -

superiorjello reblogged this · 2 months ago

superiorjello reblogged this · 2 months ago -

bloodyravenstag reblogged this · 2 months ago

bloodyravenstag reblogged this · 2 months ago -

khaia-x4 liked this · 2 months ago

khaia-x4 liked this · 2 months ago -

4nythingforourmoony89 liked this · 2 months ago

4nythingforourmoony89 liked this · 2 months ago -

andromeda-flipss reblogged this · 2 months ago

andromeda-flipss reblogged this · 2 months ago -

1kazul reblogged this · 2 months ago

1kazul reblogged this · 2 months ago -

1kazul liked this · 2 months ago

1kazul liked this · 2 months ago -

lotuslol reblogged this · 2 months ago

lotuslol reblogged this · 2 months ago -

lotuslol liked this · 2 months ago

lotuslol liked this · 2 months ago -

inexperienced-egg liked this · 2 months ago

inexperienced-egg liked this · 2 months ago -

yourlocalxiaosimp reblogged this · 2 months ago

yourlocalxiaosimp reblogged this · 2 months ago -

yourlocalxiaosimp liked this · 2 months ago

yourlocalxiaosimp liked this · 2 months ago -

krowbat liked this · 2 months ago

krowbat liked this · 2 months ago -

casiopeamomo liked this · 2 months ago

casiopeamomo liked this · 2 months ago -

kikibumblesqueaks liked this · 2 months ago

kikibumblesqueaks liked this · 2 months ago -

jaekaicx reblogged this · 2 months ago

jaekaicx reblogged this · 2 months ago -

alley--rose liked this · 2 months ago

alley--rose liked this · 2 months ago -

justa-lazygoose liked this · 2 months ago

justa-lazygoose liked this · 2 months ago -

yunerokisapsodos liked this · 2 months ago

yunerokisapsodos liked this · 2 months ago -

deddritt liked this · 2 months ago

deddritt liked this · 2 months ago -

teamugdraws reblogged this · 2 months ago

teamugdraws reblogged this · 2 months ago -

teamugdraws liked this · 2 months ago

teamugdraws liked this · 2 months ago -

marybrittany liked this · 2 months ago

marybrittany liked this · 2 months ago -

tiredgaytheatrekid reblogged this · 2 months ago

tiredgaytheatrekid reblogged this · 2 months ago