Ocrim1967 - Senza Titolo

More Posts from Ocrim1967 and Others

Ask Ethan: Why Do Gravitational Waves Travel Exactly At The Speed Of Light?

We know that the speed of electromagnetic radiation can be derived from Maxwell’s equation[s] in a vacuum. What equations (similar to Maxwell’s - perhaps?) offer a mathematical proof that Gravity Waves must travel [at the] speed of light?

If you were to somehow make the Sun disappear, you would still see its emitted light for 8 minutes and 20 seconds: the amount of time it takes light to travel from the Sun to the Earth across 150,000,000 km of space. But what about gravitation? Would the Earth continue to orbit where the Sun was for that same 8 minutes and 20 seconds, or would it fly off in a straight line immediately?

There are two ways to look at this puzzle: theoretically and experimentally/observationally. From a theoretical point of view, this represents one of the most profound differences from Newton’s gravitation to Einstein’s, and demonstrates what a revolutionary leap General Relativity was. Observationally, we only had indirect measurements until 2017, where we determined the speed of gravity and the speed of light were equal to 15 significant digits!

Gravitational waves do travel at the speed of light, which equals the speed of gravity to a better precision than ever. Here’s how we know.

(Source)

Extreme Science: Launching Sounding Rockets from The Arctic

This winter, our scientists and engineers traveled to the world’s northernmost civilian town to launch rockets equipped with cutting-edge scientific instruments.

This is the beginning of a 14-month-long campaign to study a particular region of Earth’s magnetic field — which means launching near the poles. What’s it like to launch a science rocket in these extreme conditions?

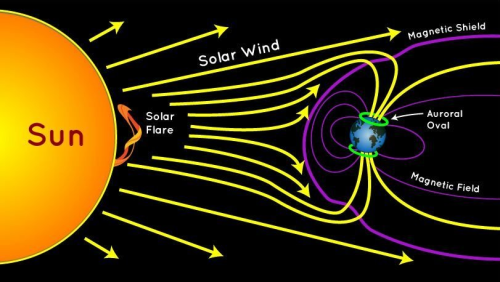

Our planet is protected by a natural magnetic field that deflects most of the particles that flow out from the Sun — the solar wind — away from our atmosphere. But near the north and south poles, two oddities in Earth’s magnetic field funnel these solar particles directly into our atmosphere. These regions are the polar cusps, and it turns out they’re the ideal spot for studying how our atmosphere interacts with space.

The scientists of the Grand Challenge Initiative — Cusp are using sounding rockets to do their research. Sounding rockets are suborbital rockets that launch to a few hundred miles in altitude, spending a few minutes in space before falling back to Earth. That means sounding rockets can carry sensitive instruments above our atmosphere to study the Sun, other stars and even distant galaxies.

They also fly directly through some of the most interesting regions of Earth’s atmosphere, and that’s what scientists are taking advantage of for their Grand Challenge experiments.

One of the ideal rocket ranges for cusp science is in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard, off the coast of Norway and within the Arctic circle. Because of its far northward position, each morning Svalbard passes directly under Earth’s magnetic cusp.

But launching in this extreme, remote environment puts another set of challenges on the mission teams. These launches need to happen during the winter, when Svalbard experiences 24/7 darkness because of Earth’s axial tilt. The launch teams can go months without seeing the Sun.

Like for all rocket launches, the science teams have to wait for the right weather conditions to launch. Because they’re studying upper atmospheric processes, some of these teams also have to wait for other science conditions, like active auroras. Auroras are created when charged particles collide with Earth’s atmosphere — often triggered by solar storms or changes in the solar wind — and they’re related to many of the upper-atmospheric processes that scientists want to study near the magnetic cusp.

But even before launch, the extreme conditions make launching rockets a tricky business — it’s so cold that the rockets must be encased in styrofoam before launch to protect them from the low temperatures and potential precipitation.

When all is finally ready, an alarm sounds throughout the town of Ny-Ålesund to alert residents to the impending launch. And then it’s up, up and away! This photo shows the launch of the twin VISIONS-2 sounding rockets on Dec. 7, 2018 from Ny-Ålesund.

These rockets are designed to break up during flight — so after launch comes clean-up. The launch teams track where debris lands so that they can retrieve the pieces later.

The next launch of the Grand Challenge Initiative is AZURE, launching from Andøya Space Center in Norway in April 2019.

For even more about what it’s like to launch science rockets in extreme conditions, check out one scientist’s notes from the field: https://go.nasa.gov/2QzyjR4

For updates on the Grand Challenge Initiative and other sounding rocket flights, visit nasa.gov/soundingrockets or follow along with NASA Wallops and NASA heliophysics on Twitter and Facebook.

@NASA_Wallops | NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility | @NASASun | NASA Sun Science

A high-definition video camera outside the space station captured stark and sobering views of Hurricane Florence, a Category 4 storm. Image Credit: ESA/NASA–A. Gerst

The scene is a late-spring afternoon in the Amazonis Planitia region of northern Mars. The view covers an area about four-tenths of a mile (644 meters) across. North is toward the top. The length of the dusty whirlwind’s shadow indicates that the dust plume reaches more than half a mile (800 meters) in height. The plume is about 30 yards or meters in diameter. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. of Arizona

A false-color image of the Great Red Spot of Jupiterfrom Voyager 1. The white oval storm directly below the Great Red Spot has the approximate diameter of Earth. NASA, Caltech/JPL

The huge storm (great white spot) churning through the atmosphere in Saturn’s northern hemisphere overtakes itself as it encircles the planet in this true-color view from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, SSI, JPL, ESA, NASA; Color Composite: Jean-Luc Dauvergne

The spinning vortex of Saturn’s north polar storm resembles a deep red rose of giant proportions surrounded by green foliage in this false-color image from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Measurements have sized the eye at 1,250 miles (2,000 kilometers) across with cloud speeds as fast as 330 miles per hour (150 meters per second). This image is among the first sunlit views of Saturn’s north pole captured by Cassini’s imaging cameras. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

Colorized infrared image of Uranus obtained on August 6, 2014, with adaptive optics on the 10-meter Keck telescope; white spots are large storms. Image credit: Imke de Pater, University of California, Berkeley / Keck Observatory images.

Neptune’s Great Dark Spot, a large anticyclonic storm similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, observed by NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1989. Credit: NASA / Jet Propulsion Lab

This true color image captured by NASA’S Cassini spacecraft before a distant flyby of Saturn’s moon Titan on June 27, 2012, shows a south polar vortex, or a swirling mass of gas around the pole in the atmosphere. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

This artist’s concept shows what the weather might look like on cool star-like bodies known as brown dwarfs. These giant balls of gas start out life like stars, but lack the mass to sustain nuclear fusion at their cores, and instead, fade and cool with time.

New research from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope suggests that most brown dwarfs are racked with colossal storms akin to Jupiter’s famous “Great Red Spot.” These storms may be marked by fierce winds, and possibly lightning. The turbulent clouds might also rain down molten iron, hot sand or salts – materials thought to make up the cloud layers of brown dwarfs.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Western Ontario/Stony Brook University

In this image, the nightmare world of HD 189733 b is the killer you never see coming. To the human eye, this far-off planet looks bright blue. But any space traveler confusing it with the friendly skies of Earth would be badly mistaken. The weather on this world is deadly. Its winds blow up to 5,400 mph (2 km/s) at seven times the speed of sound, whipping all would-be travelers in a sickening spiral around the planet. And getting caught in the rain on this planet is more than an inconvenience; it’s death by a thousand cuts. This scorching alien world possibly rains glass—sideways—in its howling winds. The cobalt blue color comes not from the reflection of a tropical ocean, as on Earth, but rather a hazy, blow-torched atmosphere containing high clouds laced with silicate particles. Image Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

Stellar Winds

Stellar winds are fast moving flows of material (protons, electrons and atoms of heavier metals) that are ejected from stars. These winds are characterised by a continuous outflow of material moving at speeds anywhere between 20 and 2,000 km/s.

In the case of the Sun, the wind ‘blows’ at a speed of 200 to 300 km/s from quiet regions, and 700 km/s from coronal holes and active regions.

The causes, ejection rates and speeds of stellar winds vary with the mass of the star. In relatively cool, low-mass stars such as the Sun, the wind is caused by the extremely high temperature (millions of degrees Kelvin) of the corona.

his high temperature is thought to be the result of interactions between magnetic fields at the star’s surface, and gives the coronal gas sufficient energy to escape the gravitational attraction of the star as a wind. Stars of this type eject only a tiny fraction of their mass per year as a stellar wind (for example, only 1 part in 1014 of the Sun’s mass is ejected in this way each year), but this still represents losses of millions of tonnes of material each second. Even over their entire lifetime, stars like our Sun lose only a tiny fraction of 1% of their mass through stellar winds.

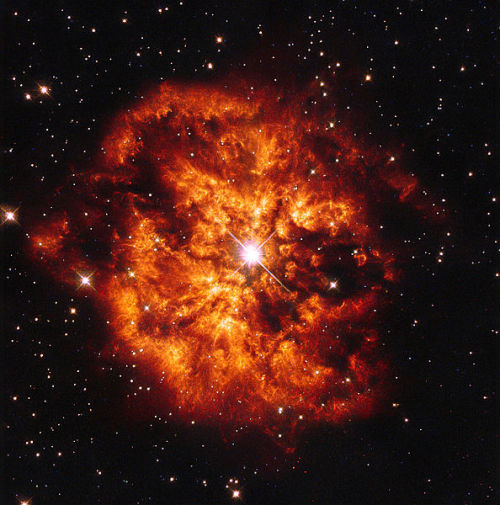

In contrast, hot, massive stars can produce stellar winds a billion times stronger than those of low-mass stars. Over their short lifetimes, they can eject many solar masses (perhaps up to 50% of their initial mass) of material in the form of 2,000 km/sec winds.

These stellar winds are driven directly by the radiation pressure from photons escaping the star. In some cases, high-mass stars can eject virtually all of their outer envelopes in winds. The result is a Wolf-Rayet star.

Stellar winds play an important part in the chemical evolution of the Universe, as they carry dust and metals back into the interstellar medium where they will be incorporated into the next generation of stars.

source (read more) + Wolf–Rayet star

Chandra Spots Extremely Long Cosmic Jet in Early Universe

http://www.sci-news.com/astronomy/chandra-extremely-long-cosmic-jet-early-universe-09436.html

(Source)

Earth: Our Oasis in Space

Earth: It’s our oasis in space, the one place we know that harbors life. That makes it a weird place – so far, we haven’t found life anywhere else in the solar system…or beyond. We study our home planet and its delicate balance of water, atmosphere and comfortable temperatures from space, the air, the ocean and the ground.

To celebrate our home, we want to see what you love about our planet. Share a picture, or several, of Earth with #PictureEarth on social media. In return, we’ll share some of our best views of our home, like this one taken from a million miles away by the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (yes, it’s EPIC).

From a DC-8 research plane flying just 1500 feet above Antarctic sea ice, we saw a massive iceberg newly calved off Pine Island Glacier. This is one in a series of large icebergs Pine Island has lost in the last few years – the glacier is one of the fastest melting in Antarctica.

It’s not just planes. We also saw the giant iceberg, known as B-46, from space. Landsat 8 tracked B-46’s progress after it broke off from Pine Island Glacier and began the journey northward, where it began to break apart and melt into the ocean.

Speaking of change, we’ve been launching Earth-observing satellites since 1958. In that time, we’ve seen some major changes. Cutting through soft, sandy soil on its journey to the Bay of Bengal, the Padma River in Bangladesh dances across the landscape in this time-lapse of 30 years’ worth of Landsat images.

Our space-based view of Earth helps us track other natural activities, too. With both a daytime and nighttime view, the Aqua satellite and the Suomi NPP satellite helped us see where wildfires were burning in California, while also tracking burn scars and smoke plumes..

Astronauts have an out-of-this-world view of Earth, literally. A camera mounted on the International Space Station captured this image of Hurricane Florence after it intensified to Category 4.

It’s not just missions studying Earth that capture views of our home planet. Parker Solar Probe turned back and looked at our home planet while en route to the Sun. Earth is the bright, round object.

Want to learn more about our home planet? Check out our third episode of NASA Science Live where we talked about Earth and what makes it so weird.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Couple goals

-

findmewherethedovesdie reblogged this · 11 months ago

findmewherethedovesdie reblogged this · 11 months ago -

tranasdogerab liked this · 1 year ago

tranasdogerab liked this · 1 year ago -

closertoyougod reblogged this · 1 year ago

closertoyougod reblogged this · 1 year ago -

closertoyougod reblogged this · 2 years ago

closertoyougod reblogged this · 2 years ago -

jesus-said-tetelestai liked this · 2 years ago

jesus-said-tetelestai liked this · 2 years ago -

closertoyougod reblogged this · 2 years ago

closertoyougod reblogged this · 2 years ago -

whoisbryana reblogged this · 2 years ago

whoisbryana reblogged this · 2 years ago -

superkalafragilisticiexpectitall liked this · 3 years ago

superkalafragilisticiexpectitall liked this · 3 years ago -

hopefulmillennial liked this · 3 years ago

hopefulmillennial liked this · 3 years ago -

takashi0 liked this · 3 years ago

takashi0 liked this · 3 years ago -

sketchmouse reblogged this · 3 years ago

sketchmouse reblogged this · 3 years ago -

sketchmouse liked this · 3 years ago

sketchmouse liked this · 3 years ago -

cokedoublezero liked this · 3 years ago

cokedoublezero liked this · 3 years ago -

bluemoonblueblood liked this · 4 years ago

bluemoonblueblood liked this · 4 years ago -

caripr94 liked this · 4 years ago

caripr94 liked this · 4 years ago -

jesus-said-tetelestai reblogged this · 4 years ago

jesus-said-tetelestai reblogged this · 4 years ago -

prayersfromheaven reblogged this · 4 years ago

prayersfromheaven reblogged this · 4 years ago -

prayersfromheaven liked this · 4 years ago

prayersfromheaven liked this · 4 years ago -

queennoziphosblog reblogged this · 4 years ago

queennoziphosblog reblogged this · 4 years ago -

firefliesinbutterflies reblogged this · 4 years ago

firefliesinbutterflies reblogged this · 4 years ago -

firefliesinbutterflies liked this · 4 years ago

firefliesinbutterflies liked this · 4 years ago -

sarahtondle liked this · 4 years ago

sarahtondle liked this · 4 years ago