Ocrim1967 - Senza Titolo

More Posts from Ocrim1967 and Others

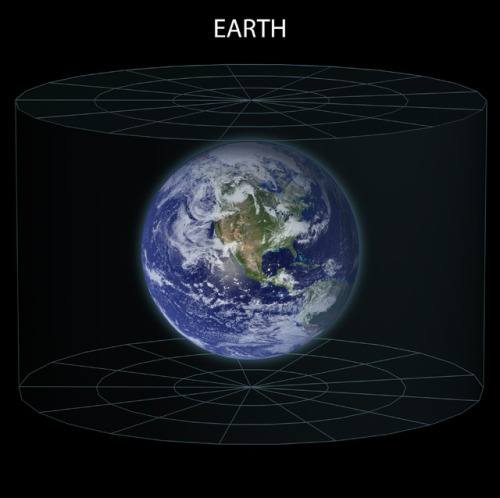

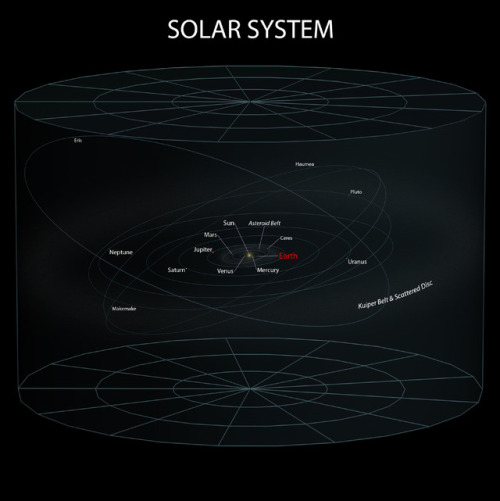

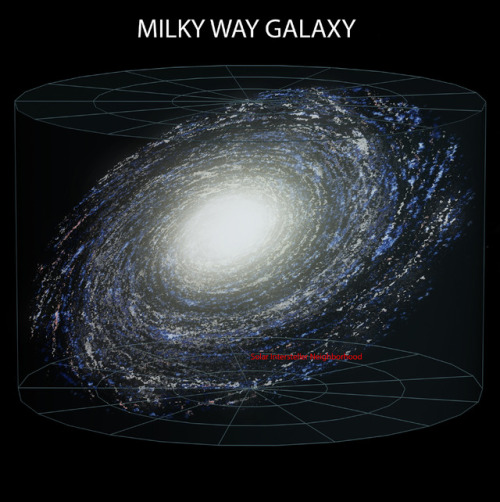

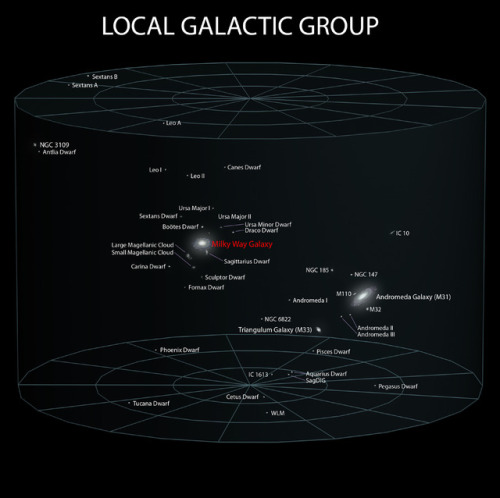

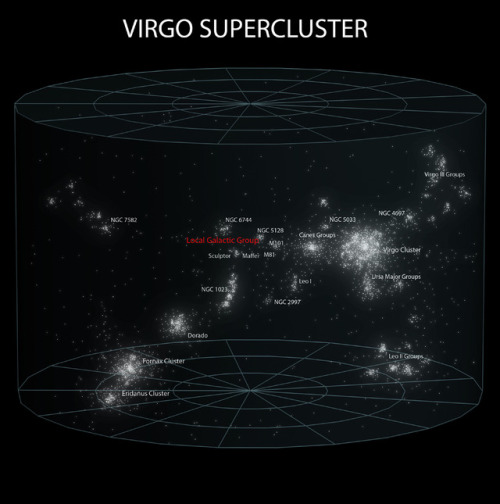

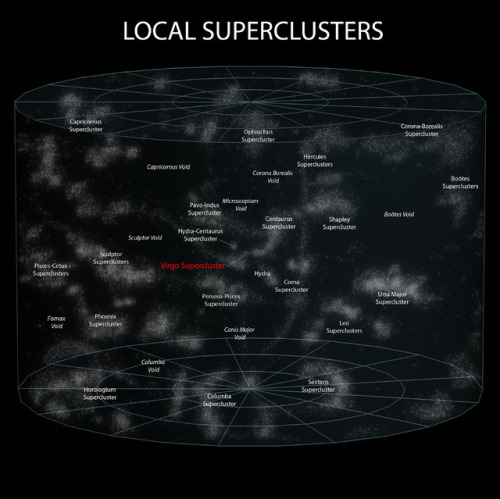

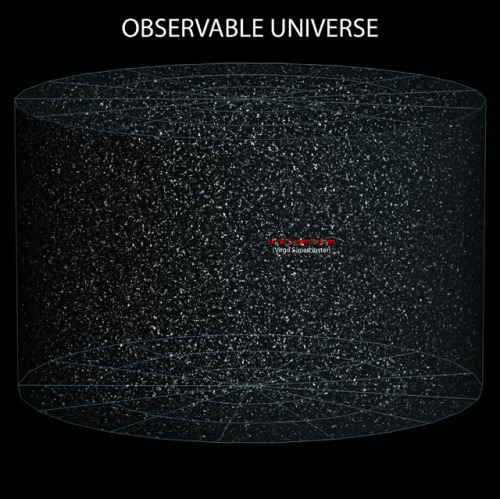

How Big is Our Galaxy, the Milky Way?

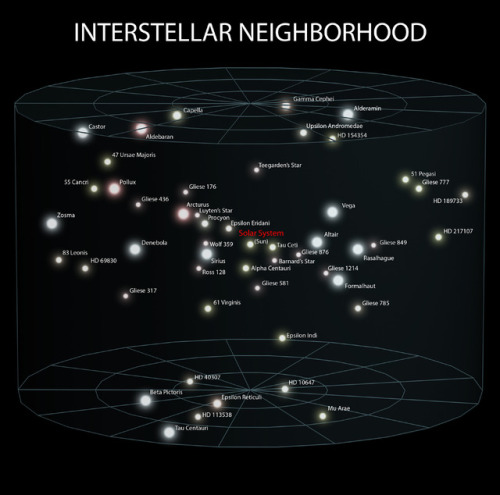

When we talk about the enormity of the cosmos, it’s easy to toss out big numbers – but far harder to wrap our minds around just how large, how far and how numerous celestial bodies like exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system – really are.

So. How big is our Milky Way Galaxy?

We use light-time to measure the vast distances of space.

It’s the distance that light travels in a specific period of time. Also: LIGHT IS FAST, nothing travels faster than light.

How far can light travel in one second? 186,000 miles. It might look even faster in metric: 300,000 kilometers in one second. See? FAST.

How far can light travel in one minute? 11,160,000 miles. We’re moving now! Light could go around the Earth a bit more than 448 times in one minute.

Speaking of Earth, how long does it take light from the Sun to reach our planet? 8.3 minutes. (It takes 43.2 minutes for sunlight to reach Jupiter, about 484 million miles away.) Light is fast, but the distances are VAST.

In an hour, light can travel 671 million miles. We’re still light-years from the nearest exoplanet, by the way. Proxima Centauri b is 4.2 light-years away. So… how far is a light-year? 5.8 TRILLION MILES.

A trip at light speed to the very edge of our solar system – the farthest reaches of the Oort Cloud, a collection of dormant comets way, WAY out there – would take about 1.87 years.

Our galaxy contains 100 to 400 billion stars and is about 100,000 light-years across!

One of the most distant exoplanets known to us in the Milky Way is Kepler-443b. Traveling at light speed, it would take 3,000 years to get there. Or 28 billion years, going 60 mph. So, you know, far.

SPACE IS BIG.

Read more here: go.nasa.gov/2FTyhgH

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

WE NEED TO ACT NOW

The role plastic products play in the daily lives of people all over the world is interminable. We could throw statistics at you all day long (e.g. Upwards of 300 MILLION tons of plastic are consumed each year), but the impact of these numbers border on inconceivable.

For those living on the coasts, a mere walk on the beach can give anyone insight into how staggering our addiction to plastic has become as bottles, cans, bags, lids and straws (just to name a few) are ever-present. In other areas that insight is more poignant as the remains of animal carcasses can frequently be observed; the plastic debris that many of them ingested or became entangled in still visible long after their death. Sadly, an overwhelming amount of plastic pollution isn’t even visible to the human eye, with much of the pollution occurring out at sea or on a microscopic level.

The short-lived use of millions of tons of plastic is, quite simply, unsustainable and dangerous. We have only begun to see the far-reaching consequences of plastic pollution and how it affects all living things. According to a study from Plymouth University, plastic pollution affects at least 700 marine species, while some estimates suggest that at least 100 million marine mammals are killed each year from plastic pollution. Here are some of the marine species most deeply impacted by plastic pollution.

Sea Turtles

Seals and Sea Lions

Seabirds

Fish

Whales and Dolphins

–> GET HERE THE OCEAN SEA PIN <–

–> GET HERE THE A LITTLE MORE KINDNESS A LITTLE LESS JUDGEMENT PIN <–

–> GET HERE 4 PACK GALAXY FISHES PINS <–

–> GET HERE THE IT’S A SMALL WORLD AFTER ALL PIN <–

–> GET HERE THE SEA LOVERS PIN <–

–> GET HERE THE IF YOU’RE LOOKING FOR A SIGN THIS IS IT PIN <–

More than ever, the fate of the ocean is in our hands. To be good stewards and leave a thriving ocean for future generations, we need to make changes big and small wherever we are.

Every purchase supports Ocean Conservation. We give a portion of our profits to Organizations that bravely fight for Marine Conservation.

If the Moon were replaced with some of our planets (at night)

Image credit: yeti dynamics

Using All of Our Senses in Space

Today, we and the National Science Foundation (NSF) announced the detection of light and a high-energy cosmic particle that both came from near a black hole billions of trillions of miles from Earth. This discovery is a big step forward in the field of multimessenger astronomy.

But wait — what is multimessenger astronomy? And why is it a big deal?

People learn about different objects through their senses: sight, touch, taste, hearing and smell. Similarly, multimessenger astronomy allows us to study the same astronomical object or event through a variety of “messengers,” which include light of all wavelengths, cosmic ray particles, gravitational waves, and neutrinos — speedy tiny particles that weigh almost nothing and rarely interact with anything. By receiving and combining different pieces of information from these different messengers, we can learn much more about these objects and events than we would from just one.

Lights, Detector, Action!

Much of what we know about the universe comes just from different wavelengths of light. We study the rotations of galaxies through radio waves and visible light, investigate the eating habits of black holes through X-rays and gamma rays, and peer into dusty star-forming regions through infrared light.

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which recently turned 10, studies the universe by detecting gamma rays — the highest-energy form of light. This allows us to investigate some of the most extreme objects in the universe.

Last fall, Fermi was involved in another multimessenger finding — the very first detection of light and gravitational waves from the same source, two merging neutron stars. In that instance, light and gravitational waves were the messengers that gave us a better understanding of the neutron stars and their explosive merger into a black hole.

Fermi has also advanced our understanding of blazars, which are galaxies with supermassive black holes at their centers. Black holes are famous for drawing material into them. But with blazars, some material near the black hole shoots outward in a pair of fast-moving jets. With blazars, one of those jets points directly at us!

Multimessenger Astronomy is Cool

Today’s announcement combines another pair of messengers. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory lies a mile under the ice in Antarctica and uses the ice itself to detect neutrinos. When IceCube caught a super-high-energy neutrino and traced its origin to a specific area of the sky, they alerted the astronomical community.

Fermi completes a scan of the entire sky about every three hours, monitoring thousands of blazars among all the bright gamma-ray sources it sees. For months it had observed a blazar producing more gamma rays than usual. Flaring is a common characteristic in blazars, so this did not attract special attention. But when the alert from IceCube came through about a neutrino coming from that same patch of sky, and the Fermi data were analyzed, this flare became a big deal!

IceCube, Fermi, and followup observations all link this neutrino to a blazar called TXS 0506+056. This event connects a neutrino to a supermassive black hole for the very first time.

Why is this such a big deal? And why haven’t we done it before? Detecting a neutrino is hard since it doesn’t interact easily with matter and can travel unaffected great distances through the universe. Neutrinos are passing through you right now and you can’t even feel a thing!

The neat thing about this discovery — and multimessenger astronomy in general — is how much more we can learn by combining observations. This blazar/neutrino connection, for example, tells us that it was protons being accelerated by the blazar’s jet. Our study of blazars, neutrinos, and other objects and events in the universe will continue with many more exciting multimessenger discoveries to come in the future.

Want to know more? Read the story HERE.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

(Source)

I love flowers 💐❤️

Happy Birthday, Albert Einstein! Genius Scientist Turns 140 Years Old Today.

The year 1905 came to be known as Einstein’s Miracle Year. He was 26 years old, and in that year he published four papers that reshaped physics.

Photoelectric effect

The first explained what’s called the photoelectric effect – one of the bases for modern-day electronics – with practical applications including television. His paper on the photoelectric effect helped pave the way for quantum mechanics by establishing that light is both a particle and a wave. For this work, Einstein was later awarded a Nobel Prize in physics.

Brownian motion

Another 1905 paper related to Brownian motion. In it, Einstein stated that the seemingly random motion of particles in a fluid (Brownian motion) was a predictable, measurable part of the movement of atoms and molecules. This helped establish the Kinetic Molecular Theory of Heat, which says that, if you heat something, its molecules begin to vibrate. At this same time, Einstein provided definitive confirmation that atoms and molecules actually exist.

Special relativity

Also in 1905, Einstein published his Special Theory of Relativity. Before it, space, time and mass all seemed to be absolutes – the same for everyone. Einstein showed that different people perceive mass, space and time differently, but that these effects don’t show up until you start moving nearly at the speed of light. Then you find, for example, that time on a swiftly moving spaceship slows down, while the mass of the ship increases. According to Einstein, a spaceship traveling at the speed of light would have infinite mass, and a body of infinite mass also has infinite resistance to motion. And that’s why nothing can accelerate to a speed faster than light speed. Because of Einstein’s special relativity, light is now seen as an absolute in a universe of shifting values for space, time and matter.

Mass-energy equivalence

The fourth 1905 paper stated that mass and energy are equivalent. You perhaps know something of this work in Einstein’s famous equation E=mc2. That equation means that energy (E) is equal to mass (m) multiplied by the speed of light © squared. Sound simple? It is, in a way. It means that matter and energy are the same thing. It’s also very profound, in part because the speed of light is a huge number. As shown by the equation, a small amount of mass can be converted into a large amount of energy … as in atomic bombs. It’s this same conversion of mass to energy, by the way, that causes stars to shine.

But Einstein didn’t stop there. As early as 1911, he’d predicted that light passing near a large mass, such as a star, would be bent. That idea led to his General Theory of Relativity in 1916.

This paper established the modern theory of gravitation and gave us the notion of curved space. Einstein showed, for example, that small masses such as planets form dimples in space-time that hardly affect the path of starlight. But big masses such as stars produce measurably curved space.

The fact that the curved space around our sun was measurable let other scientists prove Einstein’s theory. In 1919, two expeditions organized by Arthur Eddington photographed stars near the sun made visible during a solar eclipse. The displacement of these stars with respect to their true positions on the celestial sphere showed that the sun’s gravity does cause space to curve so that starlight traveling near the sun is bent from its original path. This observation confirmed Einstein’s theory, and made Einstein a household name.

Source (read more) posts about Einstein

~ wikimedia commons

Blanet: A new class of planet that could form around black holes

The dust clouds around supermassive black holes are the perfect breeding ground for an exotic new type of planet.

Blanets are fundamentally similar to planets; they have enough mass to be rounded by their own gravity, but are not massive enough to start thermonuclear fusion, just like planets that orbit stars. In 2019, a team of astronomers and exoplanetologists showed that there is a safe zone around a supermassive black hole that could harbor thousands of blanets in orbit around it.

The generally agreed theory of planet formation is that it occurs in the protoplanetary disk of gas and dust around young stars. When dust particles collide, they stick together to form larger clumps that sweep up more dust as they orbit the star. Eventually, these clumps grow large enough to become planets.

A similar process should occur around supermassive black holes. These are surrounded by huge clouds of dust and gas that bear some similarities to the protoplanetary disks around young stars. As the cloud orbits the black hole, dust particles should collide and stick together forming larger clumps that eventually become blanets.

The scale of this process is vast compared to conventional planet formation. Supermassive black holes are huge, at least a hundred thousand times the mass of our Sun. But ice particles can only form where it is cool enough for volatile compounds to condense.

This turns out to be around 100 trillion kilometers from the black hole itself, in an orbit that takes about a million years to complete. Birthdays on blanets would be few and far between!

An important limitation is the relative velocity of the dust particles in the cloud. Slow moving particles can collide and stick together, but fast-moving ones would constantly break apart in high-speed collisions. Wada and co calculated that this critical velocity must be less than about 80 meters per second.

source

The Planets and their respective sizes compared to our Sun.

-

300drag liked this · 6 years ago

300drag liked this · 6 years ago -

asgardianprincess3 liked this · 6 years ago

asgardianprincess3 liked this · 6 years ago -

snake-it-or-break-it liked this · 6 years ago

snake-it-or-break-it liked this · 6 years ago -

owlinanoaktree liked this · 6 years ago

owlinanoaktree liked this · 6 years ago -

lesbiangaybeestransform reblogged this · 6 years ago

lesbiangaybeestransform reblogged this · 6 years ago -

connanro liked this · 6 years ago

connanro liked this · 6 years ago -

bihottie4u reblogged this · 6 years ago

bihottie4u reblogged this · 6 years ago -

morningshiftcontent liked this · 6 years ago

morningshiftcontent liked this · 6 years ago -

taintedlav liked this · 6 years ago

taintedlav liked this · 6 years ago -

tapestry-of-grace-blog liked this · 6 years ago

tapestry-of-grace-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

lizard-death-the-wizard liked this · 6 years ago

lizard-death-the-wizard liked this · 6 years ago -

lovethyqueers reblogged this · 6 years ago

lovethyqueers reblogged this · 6 years ago -

basscannon-12 liked this · 6 years ago

basscannon-12 liked this · 6 years ago -

engravedinhishand liked this · 6 years ago

engravedinhishand liked this · 6 years ago -

beba-violetta liked this · 6 years ago

beba-violetta liked this · 6 years ago -

underthegrace liked this · 6 years ago

underthegrace liked this · 6 years ago -

s-tevenrogers liked this · 6 years ago

s-tevenrogers liked this · 6 years ago -

godhaschangedmeeeeeeeee liked this · 6 years ago

godhaschangedmeeeeeeeee liked this · 6 years ago -

anxiety-keeps-me-from-murder reblogged this · 6 years ago

anxiety-keeps-me-from-murder reblogged this · 6 years ago -

fluffycloudsandfairyfeet liked this · 6 years ago

fluffycloudsandfairyfeet liked this · 6 years ago -

holywanderlost reblogged this · 6 years ago

holywanderlost reblogged this · 6 years ago -

cards-from-sapphos liked this · 6 years ago

cards-from-sapphos liked this · 6 years ago -

tuggybear1974 liked this · 6 years ago

tuggybear1974 liked this · 6 years ago -

adventures-of-meg reblogged this · 6 years ago

adventures-of-meg reblogged this · 6 years ago -

adventures-of-meg liked this · 6 years ago

adventures-of-meg liked this · 6 years ago -

warrior-for-christ93 reblogged this · 6 years ago

warrior-for-christ93 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

blackrose1990me liked this · 6 years ago

blackrose1990me liked this · 6 years ago -

theater-girlie123 reblogged this · 6 years ago

theater-girlie123 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

theater-girlie123 liked this · 6 years ago

theater-girlie123 liked this · 6 years ago -

gfx9up reblogged this · 6 years ago

gfx9up reblogged this · 6 years ago -

adorableaquarius liked this · 6 years ago

adorableaquarius liked this · 6 years ago -

amayadanielsworld liked this · 6 years ago

amayadanielsworld liked this · 6 years ago -

dawn-is-breaking-soon liked this · 6 years ago

dawn-is-breaking-soon liked this · 6 years ago -

alyse-believes-in-magic reblogged this · 6 years ago

alyse-believes-in-magic reblogged this · 6 years ago -

blackgirlalmighty liked this · 6 years ago

blackgirlalmighty liked this · 6 years ago -

loveistrueblue liked this · 6 years ago

loveistrueblue liked this · 6 years ago