Am I An Asshole For Thinking This Sounds Fake As Hell Lol

am I an asshole for thinking this sounds fake as hell lol

More Posts from Hensteeths and Others

the one thing thing funnier than this caption is that the only reason they stopped doing it was that the ferret shit in the tube

i love you and we will make it thru this together

the short answer is that babies are just goated at phonology. the working theory is that in order to acquire language as fast as possible, our brains need to be receptive to any and all phonetic information from birth (and possibly even earlier; there's some evidence that prenatal infants pick up on rhythm and pitch information from the sound waves that travel from the parent to the womb). linguists have been testing them on this for a long time, and until they're about 6 month babies can distinguish phonemes from languages they've never been exposed to and who's phonology is completely different to their own. eventually the brain starts to lose that ability in order to focus on correctly articulating those sounds, which is an incredibly complex task, not to mention once you have to start arranging them into patterns to form words and sentences. basically to do takes up lot of cognitive effort that then can't be used to maintain such a massive inventory of sounds.

as for adults, I don't think it's quite accurate to say that it's impossible to learn phonology, since in order to fluently speak a second language you have to be able to understand and produce all the sounds, even if they're not 100% perfect. but in terms of why it's so much more difficult to perfect than something like syntax, it's partly of your brain not being as flexible anymore and, consequently both having a worse memory and a deeply engrained phonemic inventory, to the point that it's difficult for non-native speakers to even "hear" the difference between contrasting sounds your not familiar with (to be clear it's not that you physically can't hear it, it just doesn't register phonologically). this is also why people have consistent accents instead of making pronunciation errors at random; they're still following a set of structural rules, most likely very similar to the ones of native speakers, but with the influence of their first language changing it slightly.

so like. as i understand it, at any age, if your exposure to language is restricted to a single language, you will learn that language. like it just sort of happens, your brain figures out its grammar, semantics, etc, formal training HELPS but is not required. but this is *not* the case with the language's phonology! people will live in a foreign-phone country for years, primarily exposed to its language, they will understand it perfectly, generate it perfectly, and yet will still have a strong "accent" if not trained how to avoid it. that's weird, right? why doesnt the brain learn the phonology? (and why does it learn it perfectly as a baby?) is it too "low level", muscular-level, and that stuff gets "hardened" while higher level stuff is more flexible..?

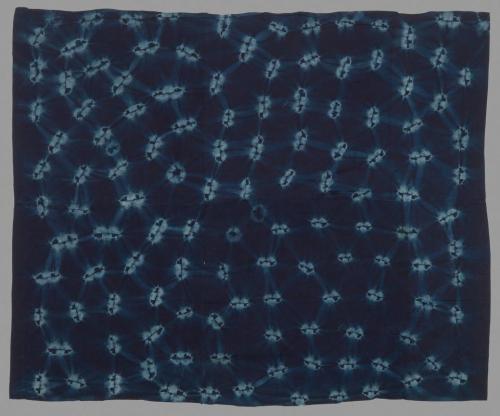

Textiles (wraps) Yoruba Cultural Group, Nigeria

circa 1984

discussion about right wing radicalisation focuses near-exclusively on men becoming white nationalists but i wonder how it might manifest elsewhere. like, imagine a heavily online subculture of mostly women and they're dedicated to rooting out degeneracy, maintaining a rigid social order, refusing to acknowledge scientific consensus, being violently paranoid of a dehumanised other, adhering to exclusively eurocentric standards of beauty and politically dedicated to exterminating a minority group (possibly one that was already historically targeted for genocide). that'd be fuckin crazy lol

the last surviving referent was just discovered and humanely euthanized by field semioticians in the salt flats of utah. apparently it was what people were referring to when they'd say. well. it doesn't matter now anyways does it.

Stop me if you've heard this one before Girls like us are rotten to the core (Let's go!)

-underscores and gabby starts

pencil crayon, 2025

I've had this image saved for months waiting for inspiration

The thing that really gets me is that a very large proportion (the majority?) of currently living, endangered indigenous American languages, at least in the US and Canada America, became endangered as a result of twentieth century policy and twentieth century developments. Residential schools, forced adoptions, and economic sabotage within the last century. And of course this is the case: languages that were already endangered 100 years ago are just dead now. But the point is that these historical wrongs are not wrongs of some distant past. The people fighting for the survival of their language here are not merely daydreaming about an imagined prelapsarian past. The are fighting for something that (depending on age) they or their parents personally experienced being robbed of. Tanadrin pointed out that the more time goes on, the harder historical wrongs are to right. This is the sort of historical wrong which is often in memory close enough that meaningful mitigation is possible.

-

patrocool reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

patrocool reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

nyx-vibes liked this · 3 weeks ago

nyx-vibes liked this · 3 weeks ago -

c--orvidae reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

c--orvidae reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

lvcifvr reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

lvcifvr reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

jabilorgball liked this · 3 weeks ago

jabilorgball liked this · 3 weeks ago -

minniestronni liked this · 3 weeks ago

minniestronni liked this · 3 weeks ago -

fvckw4d liked this · 3 weeks ago

fvckw4d liked this · 3 weeks ago -

shadowmaidenx liked this · 3 weeks ago

shadowmaidenx liked this · 3 weeks ago -

madtechnomage reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

madtechnomage reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

movethestars liked this · 3 weeks ago

movethestars liked this · 3 weeks ago -

katattqck liked this · 3 weeks ago

katattqck liked this · 3 weeks ago -

justlightmeonfire liked this · 3 weeks ago

justlightmeonfire liked this · 3 weeks ago -

mariibound2003 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

mariibound2003 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

mps-jt103 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

mps-jt103 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

deathsqueak reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

deathsqueak reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

deathsqueak liked this · 3 weeks ago

deathsqueak liked this · 3 weeks ago -

airbendling reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

airbendling reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

pauseeverythingplease liked this · 3 weeks ago

pauseeverythingplease liked this · 3 weeks ago -

mystivio liked this · 3 weeks ago

mystivio liked this · 3 weeks ago -

lemonous-snake reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

lemonous-snake reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

lemonous-snake liked this · 3 weeks ago

lemonous-snake liked this · 3 weeks ago -

spicydinosaurus liked this · 3 weeks ago

spicydinosaurus liked this · 3 weeks ago -

stunfisk-uses-attract reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

stunfisk-uses-attract reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

chinbiz liked this · 3 weeks ago

chinbiz liked this · 3 weeks ago -

spacefae reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

spacefae reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

spacefae liked this · 3 weeks ago

spacefae liked this · 3 weeks ago -

raisedbylibrarians reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

raisedbylibrarians reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

naiadkitty reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

naiadkitty reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

naiadkitty liked this · 3 weeks ago

naiadkitty liked this · 3 weeks ago -

thursdaythoughts reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

thursdaythoughts reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

forgottenwhispersinthedark reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

forgottenwhispersinthedark reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

spectralscathath liked this · 3 weeks ago

spectralscathath liked this · 3 weeks ago -

brettanomycroft reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

brettanomycroft reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

chickenclan liked this · 3 weeks ago

chickenclan liked this · 3 weeks ago -

hsttnmrks reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

hsttnmrks reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

oswako liked this · 4 weeks ago

oswako liked this · 4 weeks ago -

secretlovesoftheheart reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

secretlovesoftheheart reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

buttsbotyaasssss reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

buttsbotyaasssss reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

sarcastielle liked this · 4 weeks ago

sarcastielle liked this · 4 weeks ago -

galacticmermaid reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

galacticmermaid reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

galacticmermaid liked this · 4 weeks ago

galacticmermaid liked this · 4 weeks ago -

e-to-ipie-plus-1-equals-zero reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

e-to-ipie-plus-1-equals-zero reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

purple-hel reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

purple-hel reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

baku-links-the-weirdo reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

baku-links-the-weirdo reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

astroreoreoreoreoreoreoreo liked this · 4 weeks ago

astroreoreoreoreoreoreoreo liked this · 4 weeks ago -

ibeasadbean liked this · 4 weeks ago

ibeasadbean liked this · 4 weeks ago -

vampire-of-halogaland reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

vampire-of-halogaland reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

madscienceforidiots reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

madscienceforidiots reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

madscienceforidiots reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

madscienceforidiots reblogged this · 4 weeks ago -

liver-baby reblogged this · 4 weeks ago

liver-baby reblogged this · 4 weeks ago