I Have Been On Hiatus From This Site And Will Continue To Be For A While. Just Have No Energy To Sort

I have been on hiatus from this site and will continue to be for a while. Just have no energy to sort out who to unfollow anymore

More Posts from Enbylvania65000 and Others

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Lake It or Leave It: The Great Lakes of Nodera

It is early morning on the continent of Nodera. The twin suns bathe the landscape in a warm orange glow, as they rise together side-by-side on the eastern horizon, closer together in the sky than any other time of the year: midwinter.

The morning light casts its glow upon a tranquil scene near the shores of an enormous aquatic landscape: the Great Lakes of Nodera. The largest inland body of water on the surface of HP-02017, the Great Lakes connect to the sea by a river system opening out to the Centralic Ocean, and is comprised of a system of several interconnnected bodies of water, gouged into the landscape by the shifting tectonics of Nodera and filled up with water by the action of erosion and precipitation ofver the course of countless millenia.

In this tranquil lanlocked lake several signs of life begin to stir in the cool morning breeze, as the residents of the water's edge awaken to begin their day. On the grassy banks, a large, beaver-sized rodent begins to amble about in search of food, its bold stripes serving as a warning to potential predators of its potent defense mechanism, while up above in the sky, soar several winged figures: ones that from a distance one would suppose to be birds -- until they remembered that on this planet, there were no birds at all.

It has been another 10 million years since we last explored the diversity of this planet's evolution, and from those humble creatures of the Middle Rodentocene strange new forms have emerged. Strange new forms that on a surface view uncannily resemble the familiarity of Earth's fauna, but upon a closer look are revealed to be an entirely different creature, molded from their ancestors by the forces of evolution in an ever-changing world.

The Great Lakes of Nodera have been filled by a diverse ecosystem of aquatic life, such as forests of water plants which become home to freshwater shrish: descendants of krill that have become analogues of the fish on Earth and now have colonized this inland body of water as well. Some of them migrated upriver to spawn, found the lakes, and ultimately came to permanently settle there, becoming a part of the local ecosystem-- and a veritable food source for the descendants of the planet's first aquatic hamster, the pondrats (Aquacricetus spp.)

Ten million years have done wonders on the humble pondrat, as it comes to dominate aquatic niches throughout the lake systems. One of the more basal and populous of these are the smellcastors (Castorocricetus spp.), a group of amphibious omnivores that forage for shrish, mollusks and water plants. They are roughly the size of Earth beavers and quite closely resemble them too, save for one conspicuous feature: lacking the beaver's paddle-like tail, or indeed any tail at all, they instead propel themselves through the water with webbed, flipper-like hind feet. Smellcastors are so called for their defensive tactic of spraying an overpowering scent from modified anal musk glands that can seriously irritate a predator's sensitive nose: their bold markings are warnings of their ability, and many predators quickly learn to leave them alone.

Other descendants of the pondrat that make a living in these waters include the lutrons (Lutracricetus spp.), which are smaller and more slender than their striped and smelly cousin and spend far more time in the water, pursuing shrish with grace and agility and seldom emerging onto dry land, where their flippered hind feet make them awkward and clumsy waddlers. Another relative is the pug-billed ratypus (Brachycephalomys platypoides), a bottom-feeding pondrat with a distinctive squashed-in face and wide, sagging lips and cheeks. Long whiskers help probe for small invertebrates in the muddy pond bottom, which the ratypus slurps into its mouth and stores in its cheeks while it swims, surfacing every few minutes to breathe, chew and swallow.

And the life on the lake system isn't limited to just pondrats: in the resource-rich environments of the Great Lakes other lineages have thrived as well. The hamtelopes, specifically the long-legged ratzelles (Cervicricetus spp.), have put their elongated limbs to good use to take advantage of soft water plants growing in the shallows, becoming lanky waders that spend much of their time in knee-high water feasting on the abundance of water plants. Meanwhile, on a higher rung of the food chain lurk the searets (Lutrodiromys spp.): large aquatic ferrats that hunt like crocodiles, ambushing prey like wading hamtelopes and pondrats while swimming half-submerged, with the help of powerful crushing jaws that can drag prey underwater to drown.

But of greater interest are the vaguely-avian flyers that congregate in the skies above the Great Lakes: the ratbats (family Nyctocricetidae). Descended from the flittering jazzhand of ten million years prior, they have webbed wings of skin like bats, and fly in the daytime like birds, but are neither: like all other vertebrates in this planet, they are hamsters, albeit ones that through eons of evolution now barely resemble the familiar chubby rodent that comes to mind with this name.

The clapping, insect-seizing motions of the jazzhand have given rise to active powered flight in the ratbats, with their webbed hands merging with their patagia and becoming a true, functional wing. Two of their fingers have lengthened into supports for their wings, while the other two fingers bear large claws and toe pads, and are used for walking quadrupedally on the ground, with the wing fingers flexible enough to fold out of the way when walking and keeping them from dragging their delicate wings on the ground.

One of the most common ratbats seen in the skies around the Great Lakes is the squift (Nyctocricetus spp.), an agile insectivore that specialized to feast on the abundance of flying insects that breed and nest in water. Swarms of them congregate above the lake's surface during the breeding season, and the squifts are never far behind, darting acrobatically through the swarm to snatch up insects midair. Its close cousin, the duskflapper (Pteromys spp.) has a similar lifestyle, but instead emerges at dawn, dusk and Beta-twilight, feeding on the buffet of flying insects active at this time, and thus avoiding competition with its diurnal relative.

Ratbats have reached a massive amount of diversity since they first achieved powered flight, and among the hundreds of species living in this time are a wide array of different niches: their ranks including not only insectivores but also seed-eaters, nectar-feeders, and even predators of small ground rodents. But most notable are the shrishers (Piscivenatomys spp.), large plunge-divers with wingspans of almost six feet, and are the biggest flyers of the Late Rodentocene. They specialize on feeding on shrish, and thus have long snouts and multi-cusped molars, allowing them a good hold of their slippery prey, and not content to snatch them from the surface, dive in the water like gannets to seize their prey underwater before bursting back into the skies with their meal in tow. Specialized oil glands on their skin keep their fur water repellant, and so shrishers are commonly seen vainly preening themselves constantly, to keep their fur all greased up and resistant to sogginess when diving after their aquatic prey.

The Great Lakes of Nodera, like many isolated ecosystems, has become a sanctuary for unique and endemic lifeforms, and the unusual hamsters that have adapted to live in an aquatic environment. But their isolation is not to last: as East Nodera gradually breaks away from West Nodera with the drifting tectonics, the Great Lakes will soon be opened up to the sea- and with it, the aquatic hamsters, in the distant future, soon find themselves in a vast new body of water ripe for the taking: the Centralic Ocean itself.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

The Early Therocene: 30 million years post-establishment

Bouncing Bipeds: The Boingos and the Oingos

From the tiny, hopping jerryboas of the Rodentocene would arise the most widespread and dominant of all the herbivores on the planet: the boingos. Descended from the greater skipperroo of the Middle Rodentocene, these bipedal bounders would come to dominate the open plains, grasslands, and savannahs all across Nodera, Westerna, Easaterra and Ecatoria, crossing tthe land bridges of the Late Rodentocene and quickly expanding all across the primary continents.

Today the boingos have become one of the most diverse clades of HP-02017, spanning nearly a hundred species as of the Early Therocene. The largest species, the spotted boingo (Macropodomys giganteus) stands six feet in height and can weigh up to 190 pounds, while its other relatives are smaller, but still far larger than the tiny jerryboas they descended from.

Various species of boingos of this age have since diverged into a wide variety of forms with unique adaptations and lifestyles that set them apart from their relatives. Easily one of the most remarkable species is the streaky zibba (Saltozebroides melanoleuca), sporting bold black-and-white stripes and traveling in large herds numbering in the hundreds. When attacked by a predator, the entire herd scatters and starts bouncing away in all directions, and their erratic movements and dizzying coloration makes it difficult for a predator to zero in on a single target. Others, such as the dusky boingo (Tenuipodomys cinereus) prefer to fight than flee, sporting large claws on their hind legs that can deliver devastating kicks to an enemy.

Some of the boingos have started spreading out from the grassy plains and into other biomes as well. The twinstripe tattoroo (Gracilosaltomys lineaurum) lives in marshy wetlands, where its broad webbed feet keep it from sinking in soft ground and also makes it a surprisingly good swimmer, propelling itself with powerful kicks of its hind limbs. The desert jackaroo (Gymnocaudamys heremus), on the other hand, makes a living in a far drier clime, where its large ears, hairless tail and feet, and light-colored coat help it in losing heat in the arid climates of northern Easaterra.

Meanwhile in the continent of Easaterra lives another, smaller lineage of jerryboas descended from the prairie roobit of the Middle Rodentocene, and closely related to the boingos: the oingos. These smaller cousins of the boingos are endemic to Easaterra, where the only hamtelopes present are towering high browsers: as such, they fill the niche of low-browser and small-scale grazer that are filled by smaller hamtelopes elsewhere.

Various biomes are prevalent in Easaterra, and the oingos have adapted to thrive in a wide variety of them. Scrubland oingos (Minimosaltomys lagoides) thrive in lands dominated by low-lying bushes and shrubs, while the forest oingos (Australosaltomys longuscolli) make a living in tropical forests where they use their longer necks to reach for low-lying branges and bushes in the understory of their jungle home. And in the southernmost region of Easaterra, predominantly icy tundra and permafrost, lives the arctic oingo (Frigorimys glacies), insulated with thick white fur that it sheds in summer and regrows in winter, as well as broad, fluffy feet that prevent it from sinking in the snow.

The tremendous success of the boingos and the oingos revolve around their unique anatomy, namely their growing molars and hopping locomotion. While most herbivorous hamsters have molars with no definite roots and thus can grow constantly like their incisors, the molars of boingos and oingos grow relatively quickly and thus can better handle daily abrasion from the tough stems and sheaths of plains grasses, their favorite food.

Their bounding gaits are also incredibly efficient for traversing the open plains, with spring-like tendons in their hind legs that store energy with each landing and use it to power the next hop, allowing them to bound long distances across the grassland with scarcely any effort at all. This gait also compresses and expands their body with each hop, aiding in their breathing during strenuous activity. With more efficient dentition and locomotion, the boingos have the upper hand in the plains over the hamtelopes, which instead evolve into strange new niches to avoid their competition, such as browsers and small soft-grass grazers, and only on the continents of Borealia and Peninsulaustra, where boingos and oingos are absent, do the hamtelopes get a shot at grassland domination.

But though they look like kangaroos, move like kangaroos and hop like kangaroos due to convergent evolution, the boingos and the oingos are still placental mammals, and thus lack pouches to carry their young. Instead, much like hares and guinea pigs, they give birth to small but well-developed young that are fully-furred and open-eyed upon being born, and within an hour of their birth can already hop about and are able to follow their mother about at only one day old. Boingos and oingos typically give birth to a litter of about three to four, but sometimes as many as eight, and the sight of a mother boingo hopping along followed by her bouncing young ones in single file is a common spectacle across the plains throughout their native continents.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

In case if anyone's interested. I am another person one can interact with about this, and can think of many others. Conlanging is much more than just David J. Peterson. In fact, and I mean this without any disrespect for him, I am a bit annoyed how much Peterson, Paul Frommer, Marc Okrand and Tolkien have become in popular conscience pretty much the only conlangers - and so many of those that do know others only know YouTubers. There's so so many of us, and some of the best work is made by those who are of the community but not particularly famous outside the hobby. And some of the best resources on conlanging come from such circles.

so, i don't really know anyone who might find this as exciting as i did, so i thought i'd share it with you instead, lol. i recently wrote a fic in which i did not properly construct a conlang, but i did get to create a lot of place names and colloquialisms based on linguistic shifts and influences from surrounding languages, and it was just so much FUN? like, getting to examine the patterns of the surrounding (related) languages and determine what would be the most likely shifts for the languages in this fictional spot, and then looking at the history of the place itself and the waves of invaders, and how that affected the place names and people names and general linguistic borrowing of the surrounding areas, etc etc.

anyway, i just had such a good time, and i wanted to share it with someone else who might enjoy it! thank you in advance for letting me drop this in your box. <3

That's wonderful! If you enjoyed it here, you'll probably enjoy doing it just for the sake of it. Something I that I think would behoove fantasy authors is having a fleshed out world in which to set stories, and that includes their languages. If you work on them ahead of time, you can then drop in and write the story you want in whatever part of the world you want and all that work will be there for you to draw from. It'll be more like writing a history than writing a story, and all the places where you usually get hung up (what's this character's name going to be...? What's their family...? What's the name of their home town...?) will be easy, and you can focus on the writing itself.

Anyway, glad you enjoyed it, and I hope you can enjoy more in the future!

.אני מדבר עברית

Je parle français.

LATꟾNÉ·DꟾCERE·POSSVM

(note: Hebrew is my native language but I’m barely literate and don’t know the grammar well; my Latin is very basic.)

This point cannot be emphasised enough. I would never have been able to make any grammar at all without doing things this way.

Constraints are an amazing tool that actually make you more creative. Instead of trying to give your language ALL OF THE FEATUREs, try putting more constraints on it.

My thoughts are with everyone affected by Hamas' brutal attack on Israel, regardless of nationality, ethnicity or religion, regardless of if they live in Israel, Palestine or Lebanon. Every time someone dies is a tragedy, regardless of what side they are on or what things they did.

עם ישראל חי

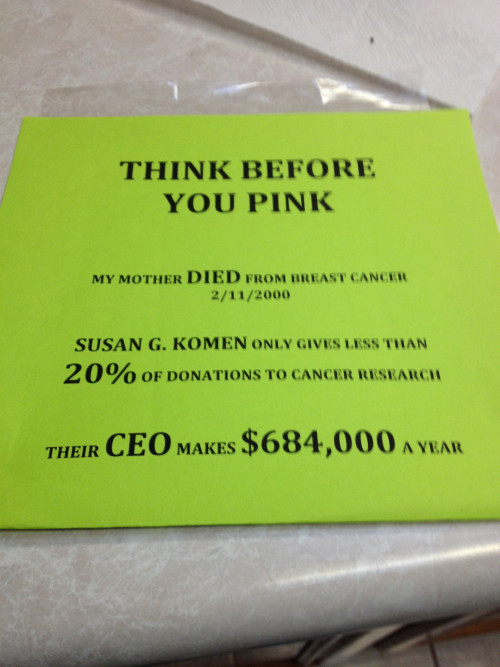

So proud of my mother for doing her own research after I sent her that meme. A sign she hung in her car window.