Enbylvania65000 - Enbylvania 6-5000

More Posts from Enbylvania65000 and Others

About 7,000 years ago, a vast lake spread hundreds of square kilometers across north-central Africa. Known to scientists as Lake Mega Chad, it covered more than 400,000 square kilometers (150,000 square miles) at its peak, making it slightly larger than the Caspian Sea, the biggest lake on Earth today.

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Full Boar Action: The Bumbaas

The bumbaas are descendants of the cavybaras that reigned in the Middle Rodentocene as the largest animals alive on the planet. Nowadays, such a distinction is gone, as other lineages continue to increase in size in the vacancy of niches: however, this particular branch of the family is still going strong, especially in the lineage of the bumbaas, adaptable omnivores that thrive throughout Ecatoria but also in Westerna and parts of Nodera too, as the cooling temperatures of the end of the Rodentocene once more resurface the land bridges which allowed new lineages to spread across the continents. And so the bumbaas spread and diversified in the different environments, foraging for grasses, shrubs, roots, fruit, invertebrates and carrion, on opportunistic occasions.

Aside from the desert bumbaa of the Great Ecatorian desert live a wide variety of other species. Other members of its genus, such as the forest bumbaa (Scrofacricetus matatai) are found elsewhere throughout Ecatoria, where, like their desert-dwelling cousin, are also avid part-time insectivores, supplementing their diet of grasses and roots with raiding insect nests: especially termites, whose mounds are abundant and a favorite of the bumbaas who break into the layers of hardened mud using their sharp tusks to access the juicy morsels within.

However, not all bumbaas closely resemble the members of this genus. Some, such as the meenypigs (Porcimys spp.) have become smaller and more slender, becoming tiny herbivores in the dense forests of Ecatoria much like mouse deer do. They feed primarily on mosses and lichens that grow on the forest floor and on the roots of trees and on logs, and with their smaller sizes prefer to run from enemies than fight them, thus favoring a build with longer legs and a leaner body.

But by far the most unusual member of the bumbaa family is the masked luchaboar (Tetracerodontomys venustafacies), a highly sexually-dimorphic species with a distinctive social system, and the only genus of bumbaa native to northern Nodera. Herds are comprised of a harem of up to a dozen females, their offspring, and a single dominant alpha male who stands out with his elaborate weaponry and brightly-colored facial markings that stand him out against the rest of the more drably-colored herd.

Most bumbaas sport only a single pair of tusks, on their lower jaw as extensions of their incisors. However, due to the constant wear and tear of abrasive vegetation on their teeth, the bumbaa's molars have also evolved to grow constantly, like their incisors, to deal with the continuous damage, and in male luchaboars the first pair of upper molars have become tusks as well: sporting a grand total of four. Males put these unusual teeth to good use, as they are fiercely territorial and aggressive: their brilliant facial markings serve as warning coloration to intimidate rivals, which they try to scare off by loud and threatening squeals, but more often than not results in a full-on wrestling match as the two males try to wrestle each other to the ground and jab each other with their tusks, which frequently results in bloody wounds and broken tusks, though as their tusks continually grow these damage is of little consequence as long as the root remains intact.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

I love it when anons/guests find my works and kudo/leave reviews, but given the new revelation that Elon Musk is using bots to mine AO3 fanfiction for a writing AI without writer's permission, my works are now archive-locked and only available for people with an AO3 account.

open family and abuse

Guys, please be aware that there are some people in the consanguinamory community or on incest forums who might throw around words like “open family” as code for abusive behaviours involving the abuse of minors. Grooming is abuse. The concept of “open family” often implies grooming, whether these people admit it or not. This topic needs to be addressed sometime more properly, but for now, please be aware. Open family is a code word used by these very sick individuals, just like the term “MAP”.

Consanguinamory allies do not support grooming.

on inattentive traits of adhd

tl;dr at the bottom

so today i was at the dentist and they saw that i take adhd meds. he said something like “your case must not be as severe as some peoples. my son has adhd and he is always bouncing off the walls. but i can just sit here and have a normal conversation with you.”

there is so SO much stigma involved with adhd and it drives me insane. i’m so sick of the “10-year-old boy who can’t sit still” stereotype. this is definitely a way that adhd is presented, and of course they’re struggles are very valid. but neurotypicals only seeing adhd through that lense is so harmful. first of all, adhd is NOT just a “kids disorder”. seriously with this one? every article you find is “my child has adhd how to fix?” or “does my child have adhd?” as if only children struggle with adhd. as if it will just magically disappear. i’m so freaking sick of it. next, it’s the lack of understand of the inattentive side of adhd. this most likely comes from many of the symptoms being more difficult for the untrained eye to pick up on. inattentive adhd isn’t “less severe” then hyperactive adhd or “easier to handle”. it’s just different! as someone who is primarily inattentive, people just seem to constantly underestimate the effect that it has on our lives. they don’t see that we spend hours and hours on a project, all they see is that we turned it in late. they don’t see that we have to actively focus on focusing, all they see is us not paying attention. we have to work longer and harder than our nt piers (i’m not saying we have to work harder than nt at everything, just many tasks that a nt would find easy and fast we don’t because of the way our brain works!), but since people can’t see that, they see us as lazy. “pay attention” “try harder” “look at the board” “are you listening” “look at me when i’m speaking to you” “it’s only a few problems”. these are things i’ve been hearing since i was in kindergarden. this goes for any neurodiverse person: you aren’t “weak” for using your accommodations. they are there to help you, to even out the playing field. i use all of my extra time every time i take a test. is it kind of annoying? yeah. but at the end of the day, it drastically helps me. school and our society in general can be very ableist, and just because you’re struggling with something that neurotypicals aren’t, doesn’t mean that you are “less capable” or “more stupid” than neurotypicals. be kind to yourself and don’t compare yourself harshly to a neurotypical who may be able to do what you can in a much shorter period of time. that’s not fair, because you have an extra barrier to work with. if you struggle with these things and feel unseen, i see you, and there are many others going through the same thing.

if you have primarily inattentive adhd, or inattentive traits in your adhd, or adhd at all, you are such a badass!

!! of course everyone with adhd is valid and a badass! and primarily hyperactive people are amazing and have some of these struggles and some different ones that i don’t fully understand i just wanted to address some things about the inattentive side. i also know everyone’s adhd is different, i don’t speak from everyone whos primarily inattentive and they won’t relate to everything i say!

*this is based off of my experience and research but i’m not saying everything here is a fact, i just want to start a discussion.*

i realize that i just wrote an extremely long post about adhd, so here’s the very crucial tl;dr:

inattentive adhd is so valid and isn’t “less severe” then more hyperactive forms of adhd.

just because people can’t always see your problems right away, that doesn’t mean they aren’t valid.

you aren’t weak for using accommodations!

just because somethings takes longer for you than a nt doesn’t mean you are bad at it, or that you are stupid.

Haven’t been feeling like logging on for a few days. I’m still on twitter break so disabled my integration. Discord is really enough social interaction for me as is.

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

The Map and World of the Late Rodentocene

The Late Rodentocene, 20 million years PE, is a world that geologically speaking has changed very little from the time the hamsters first arrived, save for the rise and fall of the sea levels due to the glaciation of the northern and southern ice caps, which in turn repeatedly exposed and submerged land bridges that allowed hamsters to migrate across continents only to later be isolated from their relatives, to diverge genetically and become a new species.

The climate of the Late Rodentocene is temperate and humid, and conducive to the growth of a wide array of biomes across its six primary continents: small Borealia in the north, Easaterra and Nodera south and east of Borealia, temperate Westerna and tropical Ecatoria across the expanse of the Centralic Ocean, and the oddly-shaped Peninsulaustra at the south of the Centralic. For a brief period spanning a few thousand years, they were all connected when the sea level dropped, bridging them all to Isla Genesis (highlighted in orange), the experimental island where hamsters were first released as test subjects in a secluded environment.

With the land bridges long since sunk, however, the continents have been cut off from one another and in their separation have developed their own unique flora and fauna, such as Peninsulaustra becoming an frigid tundra home to species adapted to the cold, and Borealia, with only a few species making it across the land bridge before it flooded over, now being a thriving hotspot for endemic species found nowhere else on the planet.

The seas are also thriving as of the Late Rodentocene: while no hamsters have colonized it, at least just yet, the warm waters are flourishing with reefs and algae forests that grow with tremendous jungles of kelp that form their own biome from small organisms that take shelter in them. Most conspicuously, however, are the lack of fish: and in the absence of the dominant marine vertebrates of Earth, strange new clades have evolved in the briny depths, to fill the gaps left vacant.

The era is a time of stability: for the next tens of millions of years, the clime and tectonics will change little and the biomes will remain habitable and little-changing. But while the world itself stagnates, its creatures do not -- and this era will be their first big hurrah, as the planet's dominant clade.

I'm puzzled as to some of my recent followers. Why am I, a queer secular Israeli, getting followed by an anti-Israel account and by a socially conservative Christian nationalist? Are these hate follows?

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Ain't No Passing Craze: The Great Ecatorian Desert

The continent of Ecatoria is a lush, warm tropical region, fed and nourished by rainfall from the South Ecatorian Sea. But not all of it is drizzled with a constant supply of precipitation: west of the mid-Ecatorian mountain ranges lies an expanse of land shielded from storms and moisture, and thus is dry and arid: the Great Ecatorian Desert, the largest desert on HP-02017 in the Late Rodentocene.

It is a hot afternoon in the Ecatorian Desert, and Alpha shines scorchingly overhead. On the western horizon Beta slowly begins to set, as the two suns are now separated by half a day: the coming of spring. But while elsewhere on Ecatoria spring would be mild and rainy, here in the Ecatorian Desert the climate is scorching in the day and chilling in the night: and despite this conditions some specialized organisms are able to eke out an existence in this inhospitable land.

A dark shadow glides overhead: a predatory ratbat, scouring from the skies above for any small creature down below. Though a rodent, this flying hunter is akin to a hawk, having adapted tremendously keen eyesight to home in on any movement down below on ground level. Down below, there is nothing but an expanse of sand and dry grass for miles, punctuated only by occasional towering plants, somewhat resembling cacti but in truth are highly-derived grass. Even the plants of this seeded world have begun evolving to fit new niches, not merely a green background in a planet of animals, but themselves competitors in the evolutionary race.

The ratbat-of-prey spots movement down below and circles around to zero in on its target. However, it quickly breaks off the hunt and soars off in search for another, easier meal: its rejected quarry is far too big to tackle. A desert-dwelling descendant of the cavybaras, it is nearly the size of its ancestor and simply too large for the ratbat to carry off, and so the predator wisely departs, while the lumbering beast below briefly watches the departing figure in curiosity, gives a huffing snort of confusion, and then proceeds on its way.

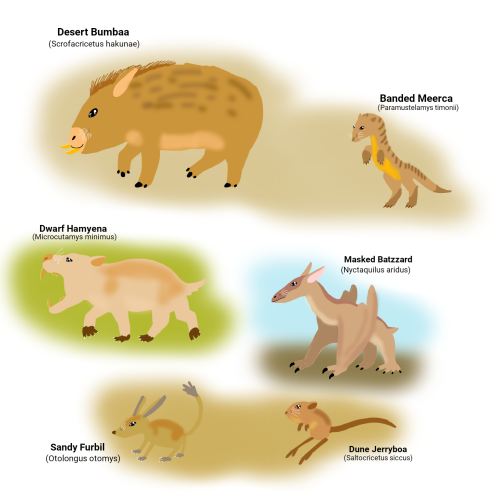

The creature in question is a direct descendant of the cavybaras, that has evolved modified extensions of its lower incisors that grow outward of its mouth, forming tusks which it uses in digging for food and for self-defense. Known as the desert bumbaa (Scrofacricetus hakunae), it is one of the several species of the genus Scrofacricetus, with its other cousins having adapted to different biomes, such as the forest bumbaa (S. matatai) and the plains bumbaa (S. porcius), which thrive in other regions of Ecatoria. The desert bumbaa differes from its cousins by its larger ears and thinner, sparser coat, which helps it lose heat in the arid climate.

The desert bumbaa is an omnivore, feeding mostly on tough shrubs and cacti-analogues in the desert. However, it also greatly relishes insects, many of which nest in burrows or underneath rocks and logs, and so the bumbaa puts its tusks to great use to dig up an abundance of bugs, overturning driftwood and uprooting plants to get at its prize. And its messy eating habits attract the attention of another desert dweller, the banded meerca (Paramustelamys timonii), a small, insectivorous ferrat that has developed a bizarre, and mutualistic, relationship with the bumbaa.

While fond of feasting on bugs, the desert bumbaa itself is plagued by insects of a nastier kind: wingless, bloodsucking flies that have converged with ticks and fleas as external parasites of mammalian hosts. These bugs cause the bumbaa great discomfort, but that is when the meerca comes to the rescue: an avid insectivore, it not only feeds upon the escaping leftovers of bumbaas while they raid insect nests, but also plucks the pests off the bumbaa's thick hide, offering them relief. The bumbaas have learned to tolerate and even welcome their presence, actively seeking them out and laying down to be groomed from parasites, while the meercas follow bumbaas around to be led to insect nests which the bumbaas then dig up, allowing the tiny meercas to share access to a buffet of bugs otherwise out of their reach.

Another benefit the meercas gain from the company of their lumbering companion is protection from predators: and indeed, there is a specialized predator prowling this dessicated wasteland: the dwarf hamyena (Microcutamys minimus). Smaller than many of its other relatives across Ecatoria but no less a deadly hunter, this badger-sized predator is descended from the hammibals of ten million years prior, and specializes on small rodents- including meercas. However, a full-grown bumbaa is too much for them to handle, their sharp tusks potentially being wielded with lethal force: as such, as long as the bumbaas are around, the meercas are safe from their small but fearsome enemy.

Other rodents also thrive in the Ecatorian Desert: furbils and jerryboas, ever present throughout the planet in all their diversity, exist in numerous forms throughout the desert landscape, feeding on insects, seeds and cactus-analogues, which they chew through their tough outer skin to reach the water-rich tissues inside. Their large ears and long tails act as heat sinks to lose excess heat, while their pale fur reflects heat and camouflages them in the light-colored sandy soil.

These tiny rodents, in turn, form a major part of the diet of the desert's primary aerial hunter, the masked batzzard (Nyctaquilus aridus). With a wingspan of about four feet, this desert ratbat circles the daytime sky, seeking out small prey such as jerryboas, furbils and meercas, which it swoops down onto, pounces on with its wing claws, and dispatches with a bite from its sharp, stabbing incisors. Hooked talons on its forelimbs ensure that prey is unable to easily escape, attacking its targets with an unusual hunting strike partly like a hawk, and partly like a cat. While live bumbaas are far too big to deal with, dead ones certainly aren't off the menu, and groups of batzzards may occasionally congregate at a carcass, where, due to their normally solitary lifestyle, nearly all their social interaction takes place, such as courtship, mating and dominance posturing.

Even in this harsh, dry landscape, life on HP-02017 has found a way. A wide, diverse collection of life thrives in this barren wilderness, despite its challenges --competing, coexisting, and even cooperating with one another, to overcome the harsh and unforgiving trials of life in the Great Ecatorian Desert.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

-

one-in-a-maxi-million reblogged this · 2 months ago

one-in-a-maxi-million reblogged this · 2 months ago -

funky-frankie reblogged this · 2 months ago

funky-frankie reblogged this · 2 months ago -

funky-frankie liked this · 2 months ago

funky-frankie liked this · 2 months ago -

wonderin-aliceland reblogged this · 2 months ago

wonderin-aliceland reblogged this · 2 months ago -

wonderin-aliceland liked this · 2 months ago

wonderin-aliceland liked this · 2 months ago -

t-empress-xxx reblogged this · 2 months ago

t-empress-xxx reblogged this · 2 months ago -

somethinginspiringhere reblogged this · 4 months ago

somethinginspiringhere reblogged this · 4 months ago -

luminescent-cnidaria reblogged this · 5 months ago

luminescent-cnidaria reblogged this · 5 months ago -

everyman1616 liked this · 7 months ago

everyman1616 liked this · 7 months ago -

stevengrantshubby reblogged this · 7 months ago

stevengrantshubby reblogged this · 7 months ago -

anastasiablackthorne liked this · 7 months ago

anastasiablackthorne liked this · 7 months ago -

justalittlebitwitchy reblogged this · 7 months ago

justalittlebitwitchy reblogged this · 7 months ago -

boxingcleverrr reblogged this · 7 months ago

boxingcleverrr reblogged this · 7 months ago -

punkwildebeest liked this · 7 months ago

punkwildebeest liked this · 7 months ago -

20drawnroses liked this · 7 months ago

20drawnroses liked this · 7 months ago -

mayeangel8 reblogged this · 7 months ago

mayeangel8 reblogged this · 7 months ago -

eliasolkkonen reblogged this · 7 months ago

eliasolkkonen reblogged this · 7 months ago -

eliasolkkonen liked this · 7 months ago

eliasolkkonen liked this · 7 months ago -

turquoiseorchid reblogged this · 7 months ago

turquoiseorchid reblogged this · 7 months ago -

destinidestati liked this · 8 months ago

destinidestati liked this · 8 months ago -

beaubambabey reblogged this · 8 months ago

beaubambabey reblogged this · 8 months ago -

tinkershar reblogged this · 8 months ago

tinkershar reblogged this · 8 months ago -

howlchaser reblogged this · 8 months ago

howlchaser reblogged this · 8 months ago -

genophobe liked this · 8 months ago

genophobe liked this · 8 months ago -

princesscedar liked this · 8 months ago

princesscedar liked this · 8 months ago -

textsfromgravityfallsblog liked this · 8 months ago

textsfromgravityfallsblog liked this · 8 months ago -

jasonthegr8 reblogged this · 8 months ago

jasonthegr8 reblogged this · 8 months ago -

localcandlesmeller liked this · 8 months ago

localcandlesmeller liked this · 8 months ago -

copperyy reblogged this · 8 months ago

copperyy reblogged this · 8 months ago -

cabbatoge reblogged this · 8 months ago

cabbatoge reblogged this · 8 months ago -

lynxloverofcandy liked this · 8 months ago

lynxloverofcandy liked this · 8 months ago -

nedthejellybean reblogged this · 8 months ago

nedthejellybean reblogged this · 8 months ago -

deepfrieddthoughts reblogged this · 8 months ago

deepfrieddthoughts reblogged this · 8 months ago -

deepfrieddthoughts liked this · 8 months ago

deepfrieddthoughts liked this · 8 months ago -

queerbabescully reblogged this · 8 months ago

queerbabescully reblogged this · 8 months ago -

eyes-onthehorizon liked this · 8 months ago

eyes-onthehorizon liked this · 8 months ago -

megudragon reblogged this · 8 months ago

megudragon reblogged this · 8 months ago -

buranael reblogged this · 8 months ago

buranael reblogged this · 8 months ago -

buranael liked this · 8 months ago

buranael liked this · 8 months ago -

trashbaby1996 reblogged this · 8 months ago

trashbaby1996 reblogged this · 8 months ago -

bellaleaf reblogged this · 8 months ago

bellaleaf reblogged this · 8 months ago -

the-technicolor-whiscash reblogged this · 8 months ago

the-technicolor-whiscash reblogged this · 8 months ago -

eggschiptune reblogged this · 8 months ago

eggschiptune reblogged this · 8 months ago -

eggschiptune liked this · 8 months ago

eggschiptune liked this · 8 months ago -

thehighercommonsense reblogged this · 8 months ago

thehighercommonsense reblogged this · 8 months ago -

comefrommanderley liked this · 8 months ago

comefrommanderley liked this · 8 months ago -

shitslikethis reblogged this · 8 months ago

shitslikethis reblogged this · 8 months ago -

dullercolors reblogged this · 8 months ago

dullercolors reblogged this · 8 months ago