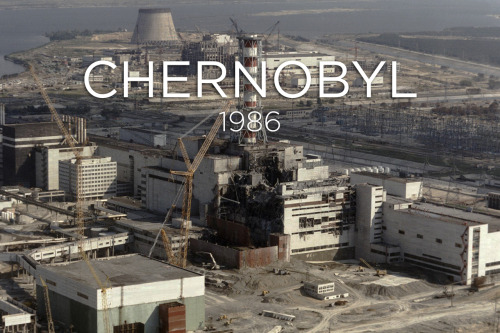

On April 26, 1986, A Power Surge Caused An Explosion At The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Near Pripyat,

On April 26, 1986, a power surge caused an explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant near Pripyat, Ukraine. A large quantity of radioactive material was released.

On May 2, 1986, the Soviet government established a “Zone of Alienation” or “Exclusion Zone” around Chernobyl – a thousand square miles of “radioactive wasteland.” All humans were evacuated. The town of Pripyat was completely abandoned.

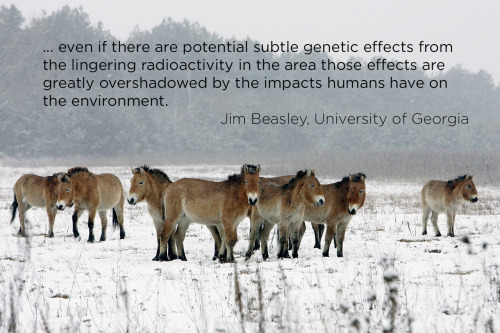

But the animals didn’t leave. And a new study, published this month in Current Biology, suggests they are doing fine. “None of our three hypotheses postulating radiation damage to large mammal populations at Chernobyl were supported by the empirical evidence,” says Jim Beasley, one of the researchers.

In fact, some of the populations have grown. These photos (mostly taken by Valeriy Yurko) come from the Belarusian side of the Exclusion Zone, and area called the Polessye State Radioecological Reserve. Kingfisher, elk, boar, baby spotted eagles, wild ponies, moose, rabbits, and wolves all make their home in the park. In some ways, human presence is worse for wildlife than a nuclear disaster.

Image credits:

1986 Chernobyl - ZUFAROV/AFP/Getty Images

Wildlife photos - Valeriy Yurko/Polessye State Radioecological Reserve

Ponies in winter - SERGEI SUPINSKY/AFP/Getty Images

More Posts from Dotmpotter and Others

“We are not facing a future without work. We are facing a future without jobs.“

READ MORE: Jobs, Work, and Universal Basic Income

Every year, 4.3 million lives are lost to diseases caused by indoor smoke from cooking, heating, oil lamps and candles. That’s one person every eight minutes - mostly women and children.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

The Sustainable Energy for All initiative is working to ensure universal access to modern energy services by 2030 - while also ramping up renewable energy and efficient energy use to help fight climate change.

Find out more here: http://www.cleanenergyislife.org/

Next-Gen Pelamis Wave Energy Converter Successfully Passes Initial Tests

Earthprints: Aletsch Glacier

One of Europe’s biggest glaciers, the Great Aletsch, coils 14 miles through the Swiss Alps - and yet this mighty river of ice could almost vanish in the lifetimes of people born today because of climate change. The glacier, 900 meters (2,950 feet) thick at one point, has retreated about 3 km (1.9 miles) since 1870 and that pace is quickening, as with many other glaciers around the globe.

That is feeding more water into the oceans and raising world sea levels. It was only after I got down onto the ice, with spikes on my boots for grip and often roped to my guide for safety, that I appreciated the full scale of the glacier, on the south side of the Jungfraujoch railway station.

And yet even the Great Aletsch glacier, the biggest in the Alps and visible from space, is under threat from the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from factories, power plants and cars that are blamed for global warming. (REUTERS) Photography by Denis Balibouse/REUTERS Read: Vast Alpine glacier could almost vanish by 2100 due to warming See more photos of the Great Aletsch and our other slideshows on Yahoo News.

An Urbanizing Planet

The video, entitled An Urbanizing Planet, takes viewers on a stunning satellite-viewed tour around our planet. By combining more than 10 datasets, and using GIS processing software and 3D graphic applications, the video shows not only where urbanization will be most extensive, but also how the majority of the expansion will occur in areas adjacent to biodiversity hotspots.

The video was produced to present the framework of a new book Global Urbanization, Biodiversity, and Ecosystems: Challenges and Opportunities — A Global Assessment. The scientific foundation of the Cities and Biodiversity Outlook project, the book presents the world’s first assessment of how global urbanization and urban growth impact biodiversity and ecosystems. It builds on contributions by more than 200 scientists worldwide.

HiPOD (2 May 2018): Clays in a Grouping of Small Craters

— 282 km above the surface. Black and white is 5 km across; enhanced color is less than 1 km.

NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

No amount of multivitamins, yoga, meditation, sweaty exercise, superfoods or extreme time management, as brilliant as all these things can be, is going to save us from the effects of too much work. This is not something we can adapt to. Not something we need to adjust the rest of our lives around. It is not possible and it’s unethical to pretend otherwise. Like a low-flying plane, the insidious culture of overwork is deafening and the only way we can really feel better is if we can find a way to make it stop.

No, it’s not you: why ‘wellness’ isn’t the answer to overwork (via brutereason)

Yet despite decades of relegation to roles as tourist attractions or advertising gimmicks, airships may be on the verge of a comeback. This resurgence will be fueled not by impractical nostalgia or fandom, but by incredible advances in airship technology that have made these craft both immeasurably safer than their predecessors, and perfect vessels for certain niche conditions. And it seems like this phoenix-like rebirth of everyone’s favorite forgotten tech might just begin in the Canadian north.

How Modern-Day Dirigibles Can Plug The World’s Transit Gaps | GOOD

-

jade-kit reblogged this · 1 month ago

jade-kit reblogged this · 1 month ago -

jade-kit liked this · 1 month ago

jade-kit liked this · 1 month ago -

conning-the-masses reblogged this · 1 month ago

conning-the-masses reblogged this · 1 month ago -

homeybee liked this · 2 months ago

homeybee liked this · 2 months ago -

harrietsc liked this · 2 months ago

harrietsc liked this · 2 months ago -

whattheforck liked this · 2 months ago

whattheforck liked this · 2 months ago -

forthefearofme reblogged this · 2 months ago

forthefearofme reblogged this · 2 months ago -

hooliganhiccups reblogged this · 2 months ago

hooliganhiccups reblogged this · 2 months ago -

graceflavored liked this · 2 months ago

graceflavored liked this · 2 months ago -

heartofanenigma liked this · 2 months ago

heartofanenigma liked this · 2 months ago -

reduxskullduggerry reblogged this · 2 months ago

reduxskullduggerry reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sleepyleopard liked this · 2 months ago

sleepyleopard liked this · 2 months ago -

fandomchaosposts liked this · 2 months ago

fandomchaosposts liked this · 2 months ago -

thedudegirlentity liked this · 2 months ago

thedudegirlentity liked this · 2 months ago -

poormeowmeowcollector reblogged this · 2 months ago

poormeowmeowcollector reblogged this · 2 months ago -

poormeowmeowcollector liked this · 2 months ago

poormeowmeowcollector liked this · 2 months ago -

cloudyrainyspring reblogged this · 2 months ago

cloudyrainyspring reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cloudyrainyspring liked this · 2 months ago

cloudyrainyspring liked this · 2 months ago -

rin-hanarin liked this · 2 months ago

rin-hanarin liked this · 2 months ago -

aastheniaa liked this · 2 months ago

aastheniaa liked this · 2 months ago -

salbeitraeume reblogged this · 2 months ago

salbeitraeume reblogged this · 2 months ago -

falle-ness liked this · 2 months ago

falle-ness liked this · 2 months ago -

cotton-glass reblogged this · 2 months ago

cotton-glass reblogged this · 2 months ago -

lenichque reblogged this · 2 months ago

lenichque reblogged this · 2 months ago -

alfys-pigeon-house reblogged this · 2 months ago

alfys-pigeon-house reblogged this · 2 months ago -

alfys-pigeon-house liked this · 2 months ago

alfys-pigeon-house liked this · 2 months ago -

special-agent-spooky-mulder liked this · 2 months ago

special-agent-spooky-mulder liked this · 2 months ago -

dick-helmet-magneto reblogged this · 2 months ago

dick-helmet-magneto reblogged this · 2 months ago -

psbjpeg liked this · 2 months ago

psbjpeg liked this · 2 months ago -

thankstothe reblogged this · 2 months ago

thankstothe reblogged this · 2 months ago -

delicate-ruins reblogged this · 2 months ago

delicate-ruins reblogged this · 2 months ago -

delicate-ruins liked this · 2 months ago

delicate-ruins liked this · 2 months ago -

jambos6 liked this · 2 months ago

jambos6 liked this · 2 months ago -

mexican-hug-cartel liked this · 2 months ago

mexican-hug-cartel liked this · 2 months ago -

gumi-bear01 reblogged this · 2 months ago

gumi-bear01 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

gumi-bear01 liked this · 2 months ago

gumi-bear01 liked this · 2 months ago -

overlyactivepingpongball liked this · 2 months ago

overlyactivepingpongball liked this · 2 months ago -

jambos6 reblogged this · 2 months ago

jambos6 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

shadow2frogs reblogged this · 2 months ago

shadow2frogs reblogged this · 2 months ago -

shadow2frogs liked this · 2 months ago

shadow2frogs liked this · 2 months ago -

junezsq-core liked this · 2 months ago

junezsq-core liked this · 2 months ago -

excalibur-pal reblogged this · 2 months ago

excalibur-pal reblogged this · 2 months ago -

excalibur-pal liked this · 2 months ago

excalibur-pal liked this · 2 months ago -

fandomgirl614 liked this · 2 months ago

fandomgirl614 liked this · 2 months ago -

patheticwetmouse liked this · 2 months ago

patheticwetmouse liked this · 2 months ago -

sugarskunkcrusade reblogged this · 2 months ago

sugarskunkcrusade reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sugarskunkcrusade liked this · 2 months ago

sugarskunkcrusade liked this · 2 months ago -

geocaprican reblogged this · 2 months ago

geocaprican reblogged this · 2 months ago -

mysrsface liked this · 2 months ago

mysrsface liked this · 2 months ago